upgrade structures and migrate to nextra v4

This commit is contained in:

840

content/Math416/Exam_reviews/Math416_E1.md

Normal file

840

content/Math416/Exam_reviews/Math416_E1.md

Normal file

@@ -0,0 +1,840 @@

|

||||

# Math 416 Midterm 1 Review

|

||||

|

||||

So everything we have learned so far is to extend the real line to the complex plane.

|

||||

|

||||

## Chapter 0 Calculus on Real values

|

||||

|

||||

### Differentiation

|

||||

|

||||

Let $f,g$ be function on real line and $c$ be a real number.

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\frac{d}{dx}(f+g)=f'+g'

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\frac{d}{dx}(cf)=cf'

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\frac{d}{dx}(fg)=f'g+fg'

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\frac{d}{dx}(f/g)=(f'g-fg')/g^2

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\frac{d}{dx}(f\circ g)=(f'\circ g)\frac{d}{dx}g

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\frac{d}{dx}x^n=nx^{n-1}

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\frac{d}{dx}e^x=e^x

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\frac{d}{dx}\ln x=\frac{1}{x}

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\frac{d}{dx}\sin x=\cos x

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\frac{d}{dx}\cos x=-\sin x

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\frac{d}{dx}\tan x=\sec^2 x

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\frac{d}{dx}\sec x=\sec x\tan x

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\frac{d}{dx}\csc x=-\csc x\cot x

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\frac{d}{dx}\sinh x=\cosh x

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\frac{d}{dx}\cosh x=\sinh x

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\frac{d}{dx}\tanh x=\operatorname{sech}^2 x

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\frac{d}{dx}\operatorname{sech} x=-\operatorname{sech}x\tanh x

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\frac{d}{dx}\operatorname{csch} x=-\operatorname{csch}x\coth x

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\frac{d}{dx}\coth x=-\operatorname{csch}^2 x

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\frac{d}{dx}\arcsin x=\frac{1}{\sqrt{1-x^2}}

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\frac{d}{dx}\arccos x=-\frac{1}{\sqrt{1-x^2}}

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\frac{d}{dx}\arctan x=\frac{1}{1+x^2}

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\frac{d}{dx}\operatorname{arccot} x=-\frac{1}{1+x^2}

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\frac{d}{dx}\operatorname{arcsec} x=\frac{1}{x\sqrt{x^2-1}}

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\frac{d}{dx}\operatorname{arccsc} x=-\frac{1}{x\sqrt{x^2-1}}

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

### Integration

|

||||

|

||||

Let $f,g$ be function on real line and $c$ be a real number.

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\int (f+g)dx=\int fdx+\int gdx

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\int cfdx=c\int fdx

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\int e^x dx=e^x

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\int \ln x dx=x\ln x-x

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\int \frac{1}{x} dx=\ln|x|

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\int \sin x dx=-\cos x

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\int \cos x dx=\sin x

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\int \tan x dx=-\ln|\cos x|

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\int \cot x dx=\ln|\sin x|

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\int \sec x dx=\ln|\sec x+\tan x|

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\int \csc x dx=\ln|\csc x-\cot x|

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\int \sinh x dx=\cosh x

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\int \cosh x dx=\sinh x

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\int \tanh x dx=\ln|\cosh x|

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\int \coth x dx=\ln|\sinh x|

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\int \operatorname{sech} x dx=2\arctan(\tanh(x/2))

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\int \operatorname{csch} x dx=\ln|\coth x-\operatorname{csch} x|

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\int \operatorname{sech}^2 x dx=\tanh x

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\int \operatorname{csch}^2 x dx=-\coth x

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\int \frac{1}{1+x^2} dx=\arctan x

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\int \frac{1}{x^2+1} dx=\arctan x

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\int \frac{1}{x^2-1} dx=\frac{1}{2}\ln|\frac{x-1}{x+1}|

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\int \frac{1}{x^2-a^2} dx=\frac{1}{2a}\ln|\frac{x-a}{x+a}|

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\int \frac{1}{x^2+a^2} dx=\frac{1}{a}\arctan(\frac{x}{a})

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\int \frac{1}{\sqrt{x^2-a^2}} dx=\ln|x+\sqrt{x^2-a^2}|

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\int \frac{1}{\sqrt{x^2+a^2}} dx=\ln|x+\sqrt{x^2+a^2}|

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

## Chapter 1 Complex Numbers

|

||||

|

||||

### Definition of complex numbers

|

||||

|

||||

An ordered pair of real numbers $(x, y)$ can be represented as a complex number $z = x + yi$, where $i$ is the imaginary unit.

|

||||

|

||||

With operations defined as:

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

(x_1 + y_1i) + (x_2 + y_2i) = (x_1 + x_2) + (y_1 + y_2)i

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

(x_1 + y_1i) \cdot (x_2 + y_2i) = (x_1x_2 - y_1y_2) + (x_1y_2 + x_2y_1)i

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

#### Modulus

|

||||

|

||||

The modulus of a complex number $z = x + yi$ is defined as

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|z| = \sqrt{x^2 + y^2}=|z\overline{z}|

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

### De Moivre's Formula

|

||||

|

||||

Every complex number $z$ can be written as $z = r(\cos \theta + i \sin \theta)$, where $r$ is the magnitude of $z$ and $\theta$ is the argument of $z$.

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

z^n = r^n(\cos n\theta + i \sin n\theta)

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

The De Moivre's formula is useful for finding the $n$th roots of a complex number.

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

z^n = r^n(\cos n\theta + i \sin n\theta)

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

### Roots of complex numbers

|

||||

|

||||

Using De Moivre's formula, we can find the $n$th roots of a complex number.

|

||||

|

||||

If $z=r(\cos \theta + i \sin \theta)$, then the $n$th roots of $z$ are given by:

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

z_k = r^{1/n}(\cos \frac{\theta + 2k\pi}{n} + i \sin \frac{\theta + 2k\pi}{n})

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

for $k = 0, 1, 2, \ldots, n-1$.

|

||||

|

||||

### Stereographic projection

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

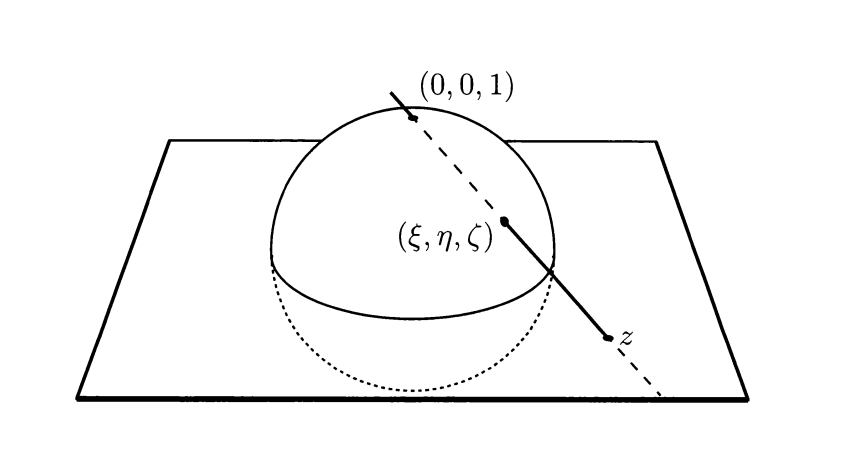

The stereographic projection is a map from the unit sphere $S^2$ to the complex plane $\mathbb{C}\setminus\{0\}$.

|

||||

|

||||

The projection is given by:

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

z\mapsto \frac{(2Re(z), 2Im(z), |z|^2-1)}{|z|^2+1}

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

The inverse map is given by:

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

(\xi,\eta, \zeta)\mapsto \frac{\xi + i\eta}{1 - \zeta}

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

## Chapter 2 Complex Differentiation

|

||||

|

||||

### Definition of complex differentiation

|

||||

|

||||

Let the complex plane $\mathbb{C}$ be defined in an open subset $G$ of $\mathbb{C}$. (Domain)

|

||||

|

||||

Then $f$ is said to be differentiable at $z_0\in G$ if the limit

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\lim_{z\to z_0} \frac{f(z)-f(z_0)}{z-z_0}

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

exists.

|

||||

|

||||

The limit is called the derivative of $f$ at $z_0$ and is denoted by $f'(z_0)$.

|

||||

|

||||

To prove that a function is differentiable, we can use the standard delta-epsilon definition of a limit.

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\left|\frac{f(z)-f(z_0)}{z-z_0} - f'(z_0)\right| < \epsilon

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

whenever $0 < |z-z_0| < \delta$.

|

||||

|

||||

With such definition, all the properties of real differentiation can be extended to complex differentiation.

|

||||

|

||||

#### Differentiation of complex functions

|

||||

|

||||

1. If $f$ is differentiable at $z_0$, then $f$ is continuous at $z_0$.

|

||||

2. If $f,g$ are differentiable at $z_0$, then $f+g, fg$ are differentiable at $z_0$.

|

||||

$$

|

||||

(f+g)'(z_0) = f'(z_0) + g'(z_0)

|

||||

$$

|

||||

$$

|

||||

(fg)'(z_0) = f'(z_0)g(z_0) + f(z_0)g'(z_0)

|

||||

$$

|

||||

3. If $f,g$ are differentiable at $z_0$ and $g(z_0)\neq 0$, then $f/g$ is differentiable at $z_0$.

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\left(\frac{f}{g}\right)'(z_0) = \frac{f'(z_0)g(z_0) - f(z_0)g'(z_0)}{g(z_0)^2}

|

||||

$$

|

||||

4. If $f$ is differentiable at $z_0$ and $g$ is differentiable at $f(z_0)$, then $g\circ f$ is differentiable at $z_0$.

|

||||

$$

|

||||

(g\circ f)'(z_0) = g'(f(z_0))f'(z_0)

|

||||

$$

|

||||

5. If $f(z)=\sum_{k=0}^n c_k(z-z_0)^k$, where $c_k\in\mathbb{C}$, then $f$ is differentiable at $z_0$ and $f'(z_0)=\sum_{k=1}^n kc_k(z_0-z_0)^{k-1}$.

|

||||

$$

|

||||

f'(z_0) = c_1 + 2c_2(z_0-z_0) + 3c_3(z_0-z_0)^2 + \cdots + nc_n(z_0-z_0)^{n-1}

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

### Cauchy-Riemann Equations

|

||||

|

||||

Let the function defined on an open subset $G$ of $\mathbb{C}$ be $f(x,y)=u(x,y)+iv(x,y)$, where $u,v$ are real-valued functions.

|

||||

|

||||

Then $f$ is differentiable at $z_0=x_0+y_0i$ if and only if the partial derivatives of $u$ and $v$ exist at $(x_0,y_0)$ and satisfy the Cauchy-Riemann equations:

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\frac{\partial u}{\partial x} = \frac{\partial v}{\partial y}, \quad \frac{\partial u}{\partial y} = -\frac{\partial v}{\partial x}

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

On the polar form, the Cauchy-Riemann equations are

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

r\frac{\partial u}{\partial r} = \frac{\partial v}{\partial \theta}, \quad \frac{\partial u}{\partial \theta} = -r\frac{\partial v}{\partial r}

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

### Holomorphic functions

|

||||

|

||||

A function $f$ is said to be holomorphic on an open subset $G$ of $\mathbb{C}$ if $f$ is differentiable at every point of $G$.

|

||||

|

||||

#### Partial differential operators

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\frac{\partial}{\partial z} = \frac{1}{2}\left(\frac{\partial}{\partial x} - i\frac{\partial}{\partial y}\right)

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\frac{\partial}{\partial \bar{z}} = \frac{1}{2}\left(\frac{\partial}{\partial x} + i\frac{\partial}{\partial y}\right)

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

This gives that

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\frac{\partial f}{\partial z} = \frac{1}{2}\left(\frac{\partial f}{\partial x} - i\frac{\partial f}{\partial y}\right)=\frac{1}{2}\left(\frac{\partial u}{\partial x} +\frac{\partial v}{\partial y}\right) + \frac{i}{2}\left(\frac{\partial v}{\partial x} - \frac{\partial u}{\partial y}\right)

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\frac{\partial f}{\partial \bar{z}} = \frac{1}{2}\left(\frac{\partial f}{\partial x} + i\frac{\partial f}{\partial y}\right)=\frac{1}{2}\left(\frac{\partial u}{\partial x} - \frac{\partial v}{\partial y}\right) + \frac{i}{2}\left(\frac{\partial u}{\partial y} + \frac{\partial v}{\partial x}\right)

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

If the function $f$ is holomorphic, then by the Cauchy-Riemann equations, we have

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\frac{\partial f}{\partial \bar{z}} = 0

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

### Conformal mappings

|

||||

|

||||

A holomorphic function $f$ is said to be conformal if it preserves the angles between the curves. More formally, if $f$ is holomorphic on an open subset $G$ of $\mathbb{C}$ and $z_0\in G$, $\gamma_1, \gamma_2$ are two curves passing through $z_0$ ($\gamma_1(t_1)=\gamma_2(t_2)=z_0$) and intersecting at an angle $\theta$, then

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\arg(f\circ\gamma_1)'(t_1) - \arg(f\circ\gamma_2)'(t_2) = \theta

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

In other words, the angle between the curves is preserved.

|

||||

|

||||

An immediate consequence is that

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\arg(f\cdot \gamma_1)'(t_1) =\arg f'(z_0) + \arg \gamma_1'(t_1)\\

|

||||

\arg(f\cdot \gamma_2)'(t_2) =\arg f'(z_0) + \arg \gamma_2'(t_2)

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

### Harmonic functions

|

||||

|

||||

A real-valued function $u$ is said to be harmonic if it satisfies the Laplace equation:

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\frac{\partial^2 u}{\partial x^2} + \frac{\partial^2 u}{\partial y^2} = 0

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

## Chapter 3 Linear Fractional Transformations

|

||||

|

||||

### Definition of linear fractional transformations

|

||||

|

||||

A linear fractional transformation is a function of the form

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\phi(z) = \frac{az+b}{cz+d}

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

where $a,b,c,d$ are complex numbers and $ad-bc\neq 0$.

|

||||

|

||||

### Properties of linear fractional transformations

|

||||

|

||||

#### Matrix form

|

||||

|

||||

A linear fractional transformation can be written as a matrix multiplication:

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\phi(z) = \begin{bmatrix}

|

||||

a & b\\

|

||||

c & d\\

|

||||

\end{bmatrix}

|

||||

\begin{bmatrix}

|

||||

z\\

|

||||

1\\

|

||||

\end{bmatrix}

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

#### Conformality

|

||||

|

||||

A linear fractional transformation is conformal.

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\phi'(z) = \frac{ad-bc}{(cz+d)^2}

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

#### Three-fold transitivity

|

||||

|

||||

If $z_1,z_2,z_3$ are distinct points in the complex plane, then there exists a unique linear fractional transformation $\phi$ such that $\phi(z_1)=\infty$, $\phi(z_2)=0$, $\phi(z_3)=1$.

|

||||

|

||||

The map is given by

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\phi(z) =\begin{cases}

|

||||

\frac{(z-z_2)(z_1-z_3)}{(z-z_1)(z_2-z_3)} & \text{if } z_1,z_2,z_3 \text{ are all finite}\\

|

||||

\frac{z-z_2}{z_3-z_2} & \text{if } z_1=\infty\\

|

||||

\frac{z_3-z_1}{z-z_1} & \text{if } z_2=\infty\\

|

||||

\frac{z-z_2}{z-z_1} & \text{if } z_3=\infty\\

|

||||

\end{cases}

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

So if $z_1,z_2,z_3$, $w_1,w_2,w_3$ are distinct points in the complex plane, then there exists a unique linear fractional transformation $\phi$ such that $\phi(z_i)=w_i$ for $i=1,2,3$.

|

||||

|

||||

#### Factorization

|

||||

|

||||

Every linear fractional transformation can be written as a composition of homothetic mappings, translations, inversions, and multiplications.

|

||||

|

||||

If $\phi(z)=\frac{az+b}{cz+d}$, then

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\phi(z) = \frac{b-ad/c}{cz+d}+\frac{a}{c}

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

#### Clircle

|

||||

|

||||

A linear-fractional transformation maps circles and lines to circles and lines.

|

||||

|

||||

## Chapter 4 Elementary Functions

|

||||

|

||||

### Exponential function

|

||||

|

||||

The exponential function is defined as

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

e^z = \sum_{n=0}^\infty \frac{z^n}{n!}

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

Let $z=x+iy$, then

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\begin{aligned}

|

||||

e^z &= e^{x+iy}\\

|

||||

&= e^x e^{iy}\\

|

||||

&= e^x\sum_{n=0}^\infty \frac{(iy)^n}{n!}\\

|

||||

&= e^x\sum_{n=0}^\infty \frac{(-1)^n y^{2n}}{(2n)!} + i \sum_{n=0}^\infty \frac{(-1)^n y^{2n+1}}{(2n+1)!}\\

|

||||

&= e^x(\cos y + i\sin y)\\

|

||||

\end{aligned}

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

So we can rewrite the polar form of a complex number as

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

z = r(\cos \theta + i\sin \theta) = re^{i\theta}

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

#### $e^x$ is holomorphic

|

||||

|

||||

Let $f(z)=e^z$, then $u(x,y)=e^x\cos y$, $v(x,y)=e^x\sin y$.

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\frac{\partial u}{\partial x} = e^x\cos y = \frac{\partial v}{\partial y}\\

|

||||

\frac{\partial u}{\partial y} = -e^x\sin y = -\frac{\partial v}{\partial x}

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

### Trigonometric functions

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\sin z = \frac{e^{iz}-e^{-iz}}{2i}, \quad \cos z = \frac{e^{iz}+e^{-iz}}{2}, \quad \tan z = \frac{\sin z}{\cos z}

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\sec z = \frac{1}{\cos z}, \quad \csc z = \frac{1}{\sin z}, \quad \cot z = \frac{1}{\tan z}

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

#### Hyperbolic functions

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\sinh z = \frac{e^z-e^{-z}}{2}, \quad \cosh z = \frac{e^z+e^{-z}}{2}, \quad \tanh z = \frac{\sinh z}{\cosh z}

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\operatorname{sech} z = \frac{1}{\cosh z}, \quad \operatorname{csch} z = \frac{1}{\sinh z}, \quad \operatorname{coth} z = \frac{1}{\tanh z}

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

### Logarithmic function

|

||||

|

||||

The logarithmic function is defined as

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\ln z=\{w\in\mathbb{C}: e^w=z\}

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

#### Properties of the logarithmic function

|

||||

|

||||

Let $z=x+iy$, then

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|e^z|=\sqrt{e^x(\cos y)^2+(\sin y)^2}=e^x

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

So we have

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\log z = \ln |z| + i\arg z

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

### Power function

|

||||

|

||||

For any two complex numbers $a,b$, we can define the power function as

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

a^b = e^{b\log a}

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

> Example:

|

||||

>

|

||||

> $$i^i=e^{i\ln i}=e^{i(\ln 1+i\frac{\pi}{2})}=e^{-\frac{\pi}{2}} $$

|

||||

>

|

||||

> $$e^{i\pi}=-1$$

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

## Chapter 5 Power Series

|

||||

|

||||

### Definition of power series

|

||||

|

||||

A power series is a series of the form

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\sum_{n=0}^\infty a_n (z-z_0)^n

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

### Properties of power series

|

||||

|

||||

#### Geometric series

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\sum_{n=0}^\infty z^n = \frac{1}{1-z}, \quad |z|<1

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

### Radius/Region of convergence

|

||||

|

||||

The radius of convergence of a power series is the largest number $R$ such that the series converges for all $z$ with $|z-z_0|<R$.

|

||||

|

||||

The region of convergence of a power series is the set of all points $z$ such that the series converges.

|

||||

|

||||

### Cauchy-Hadamard Theorem

|

||||

|

||||

The radius of convergence of a power series is given by

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

R=\frac{1}{\limsup_{n\to\infty} |a_n|^{1/n}}

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

### Derivative of power series

|

||||

|

||||

The derivative of a power series is given by

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

f'(z)=\sum_{n=1}^\infty n a_n (z-z_0)^{n-1}

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

### Cauchy Product (of power series)

|

||||

|

||||

Let $\sum_{n=0}^\infty a_n (z-z_0)^n$ and $\sum_{n=0}^\infty b_n (z-z_0)^n$ be two power series with radius of convergence $R_1$ and $R_2$ respectively.

|

||||

|

||||

Then the Cauchy product of the two series is given by

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\sum_{n=0}^\infty c_n (z-z_0)^n

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

where

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

c_n = \sum_{k=0}^n a_k b_{n-k}

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

The radius of convergence of the Cauchy product is at least $\min(R_1,R_2)$.

|

||||

|

||||

## Chapter 6 Complex Integration

|

||||

|

||||

### Definition of Riemann Integral for complex functions

|

||||

|

||||

The complex integral of a complex function $\phi$ on the closed subinterval $[a,b]$ of the real line is said to be piecewise continuous if there exists a partition $a=t_0<t_1<\cdots<t_n=b$ such that $\phi$ is continuous on each open interval $(t_{i-1},t_i)$ and has a finite limit at each discontinuity point of the closed interval $[a,b]$.

|

||||

|

||||

If $\phi$ is piecewise continuous on $[a,b]$, then the complex integral of $\phi$ on $[a,b]$ is defined as

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\int_a^b \phi(t) dt = \int_a^b \operatorname{Re}\phi(t) dt + i\int_a^b \operatorname{Im}\phi(t) dt

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

### Fundamental Theorem of Calculus

|

||||

|

||||

If $\phi$ is piecewise continuous on $[a,b]$, then

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\int_a^b \phi'(t) dt = \phi(b)-\phi(a)

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

### Triangle inequality

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\left|\int_a^b \phi(t) dt\right| \leq \int_a^b |\phi(t)| dt

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

### Integral on curve

|

||||

|

||||

Let $\gamma$ be a piecewise smooth curve in the complex plane.

|

||||

|

||||

The integral of a complex function $f$ on $\gamma$ is defined as

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\int_\gamma f(z) dz = \int_a^b f(\gamma(t))\gamma'(t) dt

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

### Favorite estimate

|

||||

|

||||

Let $\gamma:[a,b]\to\mathbb{C}$ be a piecewise smooth curve, and let $f:[a,b]\to\mathbb{C}$ be a continuous complex-valued function. Let $M$ be a real number such that $|f(z)|\leq M$ for all $z\in\gamma$. Then

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\left|\int_\gamma f(z) dz\right| \leq M\ell(\gamma)

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

where $\ell(\gamma)$ is the length of the curve $\gamma$.

|

||||

|

||||

## Chapter 7 Cauchy's Theorem

|

||||

|

||||

### Cauchy's Theorem

|

||||

|

||||

Let $\gamma$ be a closed curve in $\mathbb{C}$ and $U$ be a simply connected open subset of $\mathbb{C}$ containing $\gamma$ and its interior. Let $f$ be a holomorphic function on $U$. Then

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\int_\gamma f(z) dz = 0

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

### Cauchy's Formula for a Circle

|

||||

|

||||

Let $C$ be a counterclockwise oriented circle and let $f$ be holomorphic function defined in an open set containing $C$ and its interior. Then for any $z$ in the interior of $C$,

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

f(z)=\frac{1}{2\pi i}\int_C \frac{f(\zeta)}{\zeta-z} d\zeta

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

### Mean Value Property

|

||||

|

||||

Let the function $f$ be holomorphic on a disk $|z-z_0|<R$. Then for any $0<r<R$, let $C_r$ denote the circle with center $z_0$ and radius $r$. Then

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

f(z_0)=\frac{1}{2\pi}\int_0^{2\pi} f(z_0+re^{i\theta}) d\theta

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

The value of the function at the center of the disk is the average of the values of the function on the boundary of the disk.

|

||||

|

||||

### Cauchy Integrals

|

||||

|

||||

Let $\gamma$ be a piecewise smooth curve in $\mathbb{C}$ and let $\phi$ be a continuous complex-valued function on $\gamma$. Then the Cauchy integral of $\phi$ on $\gamma$ is the function $f$ defined in $C\setminus\gamma$ by

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

f(z)=\int_\gamma \frac{\phi(\zeta)}{\zeta-z} d\zeta

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

Cauchy Integral Formula for circle $C_r$:

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

f(z)=\frac{1}{2\pi i}\int_{C_r} \frac{f(\zeta)}{\zeta-z} d\zeta

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

> Example:

|

||||

>

|

||||

> Evaluate $$\int_{|z|=2} \frac{z}{z-1} dz$$

|

||||

>

|

||||

> Note that if we let $f(\zeta)=\zeta$ and $z=1$ is inside the circle, then we can use Cauchy Integral Formula for circle $C_r$ to evaluate the integral.

|

||||

>

|

||||

> So we have

|

||||

>

|

||||

> $$\int_{|z|=2} \frac{z}{z-1} dz = 2\pi i f(1) = 2\pi i$$

|

||||

|

||||

General Cauchy Integral Formula for circle $C_r$:

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

f^{(n)}(z)=\frac{n!}{2\pi i}\int_{C_r} \frac{f(\zeta)}{(\zeta-z)^{n+1}} d\zeta

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

> Example:

|

||||

>

|

||||

> Evaluate $$\int_{C}\frac{\sin z}{z^{38}}dz$$

|

||||

>

|

||||

> Note that if we let $f(\zeta)=\sin \zeta$ and $z=0$ is inside the circle, then we can use General Cauchy Integral Formula for circle $C_r$ to evaluate the integral.

|

||||

>

|

||||

> So we have

|

||||

>

|

||||

> $$\int_{C}\frac{\sin z}{z^{38}}dz = \frac{2\pi i}{37!} f^{(37)}(0) = \frac{2\pi i}{37!} \sin ^{(37)}(0)$$

|

||||

>

|

||||

> Note that $\sin ^{(n)}(0)=\begin{cases} 0,& n\equiv 0 \pmod{4}\\

|

||||

1,& n\equiv 1 \pmod{4}\\

|

||||

0,& n\equiv 2 \pmod{4}\\

|

||||

-1,& n\equiv 3 \pmod{4}

|

||||

\end{cases}$

|

||||

>

|

||||

> So we have

|

||||

>

|

||||

> $$\int_{C}\frac{\sin z}{z^{38}}dz = \frac{2\pi i}{37!} \sin ^{(37)}(0) = \frac{2\pi i}{37!} \cdot 1 = \frac{2\pi i}{37!}$$

|

||||

|

||||

_Cauchy integral is a easier way to evaluate the integral._

|

||||

|

||||

### Liouville's Theorem

|

||||

|

||||

If a function $f$ is entire (holomorphic on $\mathbb{C}$) and bounded, then $f$ is constant.

|

||||

|

||||

### Finding power series of holomorphic functions

|

||||

|

||||

If $f$ is holomorphic on a disk $|z-z_0|<R$, then $f$ can be represented as a power series on the disk.

|

||||

|

||||

where $a_n=\frac{f^{(n)}(z_0)}{n!}$

|

||||

|

||||

> Example:

|

||||

>

|

||||

> If $q(z)=(z-1)(z-2)(z-3)$, find the power series of $q(z)$ centered at $z=0$.

|

||||

>

|

||||

> Note that $q(z)$ is holomorphic on $\mathbb{C}$ and $q(z)=0$ at $z=1,2,3$.

|

||||

>

|

||||

> So we can use the power series of $q(z)$ centered at $z=1$.

|

||||

>

|

||||

> To solve this, we can simply expand $q(z)=(z-1)(z-2)(z-3)$ and get $q(z)=z^3-6z^2+11z-6$.

|

||||

>

|

||||

> So we have $a_0=q(1)=-6$, $a_1=q'(1)=3z^2-12z+11=11$, $a_2=\frac{q''(1)}{2!}=\frac{6z-12}{2}=-3$, $a_3=\frac{q'''(1)}{3!}=\frac{6}{6}=1$.

|

||||

>

|

||||

> So the power series of $q(z)$ centered at $z=1$ is

|

||||

>

|

||||

> $$q(z)=-6+11(z-1)-3(z-1)^2+(z-1)^3$$

|

||||

|

||||

### Fundamental Theorem of Algebra

|

||||

|

||||

Every non-constant polynomial with complex coefficients has a root in $\mathbb{C}$.

|

||||

|

||||

Can be factored into linear factors:

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

p(z)=a_n(z-z_1)(z-z_2)\cdots(z-z_n)

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

We can treat holomorphic functions as polynomials.

|

||||

|

||||

$f$ has zero of order $m$ at $z_0$ if and only if $f(z)=(z-z_0)^m g(z)$ for some holomorphic $g(z)$ and $g(z_0)\neq 0$.

|

||||

|

||||

### Zeros of holomorphic functions

|

||||

|

||||

If $f$ is holomorphic on a disk $|z-z_0|<R$ and $f$ has a zero of order $m$ at $z_0$, then $f(z_0)=0$, $f'(z_0)=0$, $f''(z_0)=0$, $\cdots$, $f^{(m-1)}(z_0)=0$ and $f^{(m)}(z_0)\neq 0$.

|

||||

|

||||

And there exists a holomorphic function $g$ on the disk such that $f(z)=(z-z_0)^m g(z)$ and $g(z_0)\neq 0$.

|

||||

|

||||

> Example:

|

||||

>

|

||||

> Find zeros of $f(z)=\cos(z\frac{\pi}{2})$

|

||||

>

|

||||

> Note that $f(z)=0$ if and only if $z\frac{\pi}{2}=(2k+1)\frac{\pi}{2}$ for some integer $k$.

|

||||

>

|

||||

> So the zeros of $f(z)$ are $z=(2k+1)$ for some integer $k$.

|

||||

>

|

||||

> The order of the zero is $1$ since $f'(z)=-\frac{\pi}{2}\sin(z\frac{\pi}{2})$ and $f'(z)\neq 0$ for all $z=(2k+1)$.

|

||||

|

||||

If $f$ vanishes to infinite order at $z_0$ (that is, $f(z_0)=f'(z_0)=f''(z_0)=\cdots=0$), then $f(z)\equiv 0$ on the connected open set $U$ containing $z_0$.

|

||||

|

||||

### Identity Theorem

|

||||

|

||||

If $f$ and $g$ are holomorphic on a connected open set $U\subset\mathbb{C}$ and $f(z)=g(z)$ for all $z$ in a subset of $U$ that has a limit point in $U$, then $f(z)=g(z)$ for all $z\in U$.

|

||||

|

||||

Key: consider $h(z)=f(z)-g(z)$, prove $h(z)\equiv 0$ on $U$ by applying the zero of holomorphic function.

|

||||

|

||||

### Weierstrass Theorem

|

||||

|

||||

Limit of a sequence of holomorphic functions is holomorphic.

|

||||

|

||||

Let $f_n$ be a sequence of holomorphic functions on a domain $D\subset\mathbb{C}$ that converges uniformly to $f$ on every compact subset of $D$. Then $f$ is holomorphic on $D$.

|

||||

|

||||

### Maximum Modulus Principle

|

||||

|

||||

If $f$ is a non-constant holomorphic function on a domain $D\subset\mathbb{C}$, then $|f|$ does not attain a maximum value in $D$.

|

||||

|

||||

#### Corollary: Minimum Modulus Principle

|

||||

|

||||

If $f$ is a non-constant holomorphic function on a domain $D\subset\mathbb{C}$, then $\frac{1}{f}$ does not attain a minimum value in $D$.

|

||||

|

||||

### Schwarz Lemma

|

||||

|

||||

If $f$ is a holomorphic function on the unit disk $|z|<1$ and $|f(z)|\leq |z|$, then $|f'(0)|\leq 1$.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

279

content/Math416/Exam_reviews/Math416_Final.md

Normal file

279

content/Math416/Exam_reviews/Math416_Final.md

Normal file

@@ -0,0 +1,279 @@

|

||||

# Math 416 Final Review

|

||||

|

||||

Story after Cauchy's theorem

|

||||

|

||||

## Chapter 7: Cauchy's Theorem

|

||||

|

||||

### Existence of harmonic conjugate

|

||||

|

||||

Suppose $f=u+iv$ is holomorphic on a domain $U\subset\mathbb{C}$. Then $u=\Re f$ is harmonic on $U$. That is $\Delta u=\frac{\partial^2 u}{\partial x^2}+\frac{\partial^2 u}{\partial y^2}=0$.

|

||||

|

||||

Moreover, there exists $g\in O(U)$ such that $g$ is unique up to an additive imaginary constant.

|

||||

|

||||

> Example:

|

||||

>

|

||||

> Find a harmonic conjugate of $u(x,y)=\log|\frac{z}{z-1}|$

|

||||

>

|

||||

> Note that $\log(\frac{z}{z-1})=\log \left|\frac{z}{z-1}\right|+i(\arg(z)-\arg(z-1))$ is harmonic on $\mathbb{C}\setminus\{1\}$.

|

||||

>

|

||||

> So the harmonic conjugate of $u(x,y)=\log|\frac{z}{z-1}|$ is $v(x,y)=\arg(z)-\arg(z-1)+C$ where $C$ is a constant.

|

||||

>

|

||||

> Note that the harmonic conjugate may exist locally but not globally. (e.g. $u(x,y)=\log|z(z-1)|$ has a local harmonic conjugate $i(\arg(z)+\arg(z-1)+C)$ but this is not a well defined function since $\arg(z)+\arg(z-1)$ is not single-valued.)

|

||||

|

||||

### Corollary for harmonic functions

|

||||

|

||||

#### Theorem 7.19

|

||||

|

||||

Harmonic function are infinitely differentiable.

|

||||

|

||||

#### Theorem 7.20

|

||||

|

||||

Mean value property of harmonic functions.

|

||||

|

||||

Let $u$ be harmonic on an open set of $\Omega$, then

|

||||

|

||||

$$u(z_0)=\frac{1}{2\pi}\int_0^{2\pi} u(z_0+re^{i\theta}) d\theta$$

|

||||

|

||||

for any $z_0\in\Omega$ and $r>0$ such that $D(z_0,r)\subset\Omega$.

|

||||

|

||||

#### Theorem 7.21

|

||||

|

||||

Identity theorem for harmonic functions.

|

||||

|

||||

Let $u$ be harmonic on a domain $\Omega$. If $u=0$ on some open set $G\subset\Omega$, then $u\equiv 0$ on $\Omega$.

|

||||

|

||||

#### Theorem 7.22

|

||||

|

||||

Maximum principle for harmonic functions.

|

||||

|

||||

Let $u$ be a non-constant real-valued harmonic function on a domain $\Omega$. Then $|u|$ does not attain a maximum value in $\Omega$.

|

||||

|

||||

## Chapter 8: Laurent Series and Isolated Singularities

|

||||

|

||||

### Laurent Series

|

||||

|

||||

Laurent series is a generalization of Taylor series.

|

||||

|

||||

Laurent series is a power series of the form

|

||||

|

||||

$$f(z)=\sum_{n=-\infty}^{\infty} a_n (z-z_0)^n$$

|

||||

|

||||

where

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

a_k=\frac{1}{2\pi i}\int_{C_r}\frac{f(z)}{(z-z_0)^{k+1}}dz

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

The series converges on an annulus $R_1<|z-z_0|<R_2$.

|

||||

|

||||

where $R_1=\limsup_{n\to\infty} |a_{-n}|^{1/n}$ and $R_2=\frac{1}{\limsup_{n\to\infty} |a_n|^{1/n}}$.

|

||||

|

||||

### Cauchy's Formula for an Annulus

|

||||

|

||||

Let $f$ be holomorphic on an annulus $R_1<r_1<|z-z_0|<r_2<R_2$. And $w\in A(z_0;R_1,R_2)$. Find the Annulus $w\in A(z_0;r_1,r_2)$

|

||||

|

||||

Then

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

f(w)=\frac{1}{2\pi i}\int_{C_{r_1}}\frac{f(z)}{z-w}dz-\frac{1}{2\pi i}\int_{C_{r_2}}\frac{f(z)}{z-w}dz

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

### Isolated singularities

|

||||

|

||||

Let $f$ be holomorphic on $0<|z-z_0|<R$ (The punctured disk of radius $R$ centered at $z_0$). If there exists a Laurent series of $f$ convergent on $0<|z-z_0|<R$, then $z_0$ is called an isolated singularity of $f$.

|

||||

|

||||

The series $f(z)=\sum_{n=-\infty}^{-1}a_n(z-z_0)^n$ is called the principle part of Laurent series of $f$ at $z_0$.

|

||||

|

||||

#### Removable singularities

|

||||

|

||||

If the principle part of Laurent series of $f$ at $z_0$ is zero, then $z_0$ is called a removable singularity of $f$.

|

||||

|

||||

Criterion for a removable singularity:

|

||||

|

||||

If $f$ is bounded on $0<|z-z_0|<R$, then $z_0$ is a removable singularity.

|

||||

|

||||

> Example:

|

||||

>

|

||||

> $f(z)=\frac{1}{e^z-1}$ has a removable singularity at $z=0$.

|

||||

>

|

||||

> The Laurent series of $f$ at $z=0$ is

|

||||

>

|

||||

> $$f(z)=\frac{1}{z}+\sum_{n=0}^{\infty}\frac{z^n}{n!}$$

|

||||

>

|

||||

> The principle part is zero, so $z=0$ is a removable singularity.

|

||||

|

||||

#### Poles

|

||||

|

||||

If the principle part of Laurent series of $f$ at $z_0$ is a finite sum, then $z_0$ is called a pole of $f$.

|

||||

|

||||

Criterion for a pole:

|

||||

|

||||

If $f$ has an isolated singularity at $z_0$, and $\lim_{z\to z_0}|f(z)|=\infty$, then $z_0$ is a pole of $f$.

|

||||

|

||||

> Example:

|

||||

>

|

||||

> $f(z)=\frac{1}{z^2}$ has a pole at $z=0$.

|

||||

>

|

||||

> The Laurent series of $f$ at $z=0$ is

|

||||

>

|

||||

> $$f(z)=\frac{1}{z^2}$$

|

||||

>

|

||||

> The principle part is $\frac{1}{z^2}$, so $z=0$ is a pole.

|

||||

|

||||

#### Essential singularities

|

||||

|

||||

If $f$ has an isolated singularity at $z_0$, and it is neither a removable singularity nor a pole, then $z_0$ is called an essential singularity of $f$.

|

||||

|

||||

"Criterion" for an essential singularity:

|

||||

|

||||

If the principle part of Laurent series of $f$ at $z_0$ has infinitely many non-zero coefficients corresponding to negative powers of $z-z_0$, then $z_0$ is called an essential singularity of $f$.

|

||||

|

||||

> Example:

|

||||

>

|

||||

> $f(z)=\sin(\frac{1}{z})$ has an essential singularity at $z=0$.

|

||||

>

|

||||

> The Laurent series of $f$ at $z=0$ is

|

||||

>

|

||||

> $$f(z)=\frac{1}{z}-\frac{1}{6z^3}+\frac{1}{120z^5}-\cdots$$

|

||||

>

|

||||

> Since there are infinitely many non-zero coefficients corresponding to negative powers of $z$, $z=0$ is an essential singularity.

|

||||

|

||||

#### Singularities at infinity

|

||||

|

||||

We say $f$ has a singularity (removable, pole, or essential) at infinity if $f(1/z)$ has an isolated singularity (removable, pole, or essential) at $z=0$.

|

||||

|

||||

> Example:

|

||||

>

|

||||

> $f(z)=\frac{z^4}{(z-1)(z-3)}$ has a pole of order 2 at infinity.

|

||||

>

|

||||

> Plug in $z=1/w$, we get $f(1/w)=\frac{1}{w^2}\frac{1}{(1/w-1)(1/w-3)}=\frac{1}{w^2}\frac{1}{(1-w)(1-3w)}=\frac{1}{w^2}(1+O(w))$, which has pole of order 2 at $w=0$.

|

||||

|

||||

#### Residue

|

||||

|

||||

The residue of $f$ at $z_0$ is the coefficient of the term $(z-z_0)^{-1}$ in the Laurent series of $f$ at $z_0$.

|

||||

|

||||

> Example:

|

||||

>

|

||||

> $f(z)=\frac{1}{z^2}$ has a residue of 0 at $z=0$.

|

||||

>

|

||||

> $f(z)=\frac{z^3}{z-1}$ has a residue of 1 at $z=1$.

|

||||

|

||||

Residue for pole with higher order:

|

||||

|

||||

If $f$ has a pole of order $n$ at $z_0$, then the residue of $f$ at $z_0$ is

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\operatorname{res}(f,z_0)=\frac{1}{(n-1)!}\lim_{z\to z_0}\frac{d^{n-1}}{dz^{n-1}}((z-z_0)^nf(z))

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

## Chapter 9: Generalized Cauchy's Theorem

|

||||

|

||||

### Winding number

|

||||

|

||||

The winding number of a closed curve $C$ with respect to a point $z_0$ is

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\operatorname{ind}_C(z_0)=\frac{1}{2\pi i}\int_C\frac{1}{z-z_0}dz

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

_the winding number is the number of times the curve $C$ winds around the point $z_0$ counterclockwise. (May be negative)_

|

||||

|

||||

### Contour integrals

|

||||

|

||||

A contour is a piecewise continuous curve $\gamma:[a,b]\to\mathbb{C}$ with integer coefficients.

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\Gamma=\sum_{i=1}^p n_j\gamma_j

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

where $\gamma_j:[a_j,b_j]\to\mathbb{C}$ is continuous closed curve and $n_j\in\mathbb{Z}$.

|

||||

|

||||

### Interior of a curve

|

||||

|

||||

The interior of a curve is the set of points $z\in\mathbb{C}$ such that $\operatorname{ind}_{\Gamma}(z)\neq 0$.

|

||||

|

||||

The winding number of contour $\Gamma$ is the sum of the winding numbers of the components of $\Gamma$ around $z_0$.

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\operatorname{ind}_{\Gamma}(z)=\sum_{j=1}^p n_j\operatorname{ind}_{\gamma_j}(z)

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

### Separation lemma

|

||||

|

||||

Let $\Omega\subseteq\mathbb{C}$ be a domain and $K\subset \Omega$ be compact. Then there exists a simple contour $\Gamma\subset \Omega\setminus K$ such that $K\subset \operatorname{int}_{\Gamma}(\Gamma)\subset \Omega$.

|

||||

|

||||

Key idea:

|

||||

|

||||

Let $0<\delta<d(K,\partial \Omega)$, then draw the grid lines and trace the contour.

|

||||

|

||||

### Residue theorem

|

||||

|

||||

Let $\Omega$ be a domain, $\Gamma$ be a contour such that $\Gamma\cap \operatorname{int}(\Gamma)\subset \Omega$. Let $f$ be holomorphic on $\Omega\setminus \{z_1,z_2,\cdots,z_p\}$ and $z_1,z_2,\cdots,z_p$ are finitely many points in $\Omega$, where $z_1,z_2,\cdots,z_p\notin \Gamma$. Then

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\int_{\Gamma}f(z)dz=2\pi i\sum_{j=1}^p \operatorname{res}(f,z_j)

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

Key: Prove by circle around each singularity and connect them using two way paths.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

### Homotopy*

|

||||

|

||||

Suppose $\gamma_0, \gamma_1$ are two curves from

|

||||

$[0,1]$ to $\Omega$ with same end points $P,Q$.

|

||||

|

||||

A homotopy is a continuous function of curves $\gamma_t, 0\leq t\leq 1$, deforming $\gamma_0$ to $\gamma_1$, keeping the end points fixed.

|

||||

|

||||

Formally, if $H:[0,1]\times [0,1]\to \Omega$ is a continuous function satsifying

|

||||

|

||||

1. $H(s,0)=\gamma_0(s)$, $\forall s\in [0,1]$

|

||||

2. $H(s,1)=\gamma_1(s)$, $\forall s\in [0,1]$

|

||||

3. $H(0,t)=P$, $\forall t\in [0,1]$

|

||||

4. $H(1,t)=Q$, $\forall t\in [0,1]$

|

||||

|

||||

Then we say $H$ is a homotopy between $\gamma_0$ and $\gamma_1$. (If $\gamma_0$ and $\gamma_1$ are closed curves, $Q=P$)

|

||||

|

||||

#### Lemma 9.12 Technical Lemma

|

||||

|

||||

Let $\phi:[0,1]\times [0,1]\to \mathbb{C}\setminus \{0\}$ is continuous. Then there exists a continuous map $\psi:[0,1]\times [0,1]\to \mathbb{C}$ such that $e^\phi=\psi$. Moreover, $\psi$ is unique up to an additive constant in $2\pi i\mathbb{Z}$.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

### General approach to evaluate definite integrals

|

||||

|

||||

Choose a contour so that one side is the desired integral.

|

||||

|

||||

Handle the other sides using:

|

||||

|

||||

- Symmetry

|

||||

- Favorite estimate

|

||||

- Bound function by another function whose integral goes to 0

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

Reference in New Issue

Block a user