Merge branch 'main' of https://github.com/Trance-0/NoteNextra

This commit is contained in:

148

pages/CSE559A/CSE559A_L10.md

Normal file

148

pages/CSE559A/CSE559A_L10.md

Normal file

@@ -0,0 +1,148 @@

|

||||

# CSE559A Lecture 10

|

||||

|

||||

## Convolutional Neural Networks

|

||||

|

||||

### Convolutional Layer

|

||||

|

||||

Output feature map resolution depends on padding and stride

|

||||

|

||||

Padding: add zeros around the input image

|

||||

|

||||

Stride: the step of the convolution

|

||||

|

||||

Example:

|

||||

|

||||

1. Convolutional layer for 5x5 image with 3x3 kernel, padding 1, stride 1 (no skipping pixels)

|

||||

- Input: 5x5 image

|

||||

- Output: 3x3 feature map, (5-3+2*1)/1+1=5

|

||||

2. Convolutional layer for 5x5 image with 3x3 kernel, padding 1, stride 2 (skipping pixels)

|

||||

- Input: 5x5 image

|

||||

- Output: 2x2 feature map, (5-3+2*1)/2+1=2

|

||||

|

||||

_Learned weights can be thought of as local templates_

|

||||

|

||||

```python

|

||||

import torch

|

||||

import torch.nn as nn

|

||||

|

||||

# suppose input image is HxWx3 (assume RGB image)

|

||||

|

||||

conv_layer = nn.Conv2d(in_channels=3, # input channel, input is HxWx3

|

||||

out_channels=64, # output channel (number of filters), output is HxWx64

|

||||

kernel_size=3, # kernel size

|

||||

padding=1, # padding, this ensures that the output feature map has the same resolution as the input image, H_out=H_in, W_out=W_in

|

||||

stride=1) # stride

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

Usually followed by a ReLU activation function

|

||||

|

||||

```python

|

||||

conv_layer = nn.Conv2d(in_channels=3, out_channels=64, kernel_size=3, padding=1, stride=1)

|

||||

relu = nn.ReLU()

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

Suppose input image is $H\times W\times K$, the output feature map is $H\times W\times L$ with kernel size $F\times F$, this takes $F^2\times K\times L\times H\times W$ parameters

|

||||

|

||||

Each operation $D\times (K^2C)$ matrix with $(K^2C)\times N$ matrix, assume $D$ filters and $C$ output channels.

|

||||

|

||||

### Variants 1x1 convolutions, depthwise convolutions

|

||||

|

||||

#### 1x1 convolutions

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

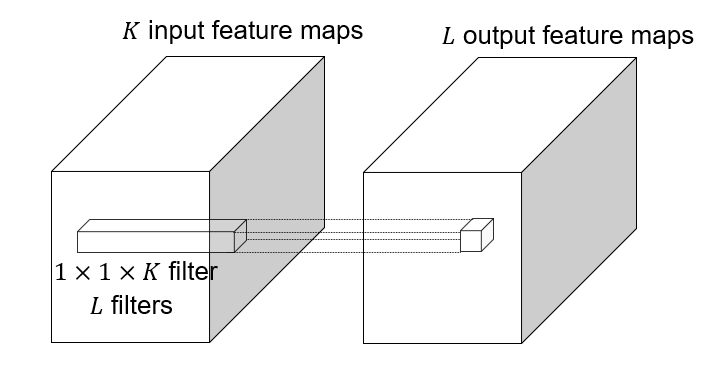

1x1 convolution: $F=1$, this layer do convolution in the pixel level, it is **pixel-wise** convolution for the feature.

|

||||

|

||||

Used to save computation, reduce the number of parameters.

|

||||

|

||||

Example: 3x3 conv layer with 256 channels at input and output.

|

||||

|

||||

Option 1: naive way:

|

||||

|

||||

```python

|

||||

conv_layer = nn.Conv2d(in_channels=256, out_channels=256, kernel_size=3, padding=1, stride=1)

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

This takes $256\times 3 \times 3\times 256=524,288$ parameters.

|

||||

|

||||

Option 2: 1x1 convolution:

|

||||

|

||||

```python

|

||||

conv_layer = nn.Conv2d(in_channels=256, out_channels=64, kernel_size=1, padding=0, stride=1)

|

||||

conv_layer = nn.Conv2d(in_channels=64, out_channels=64, kernel_size=3, padding=1, stride=1)

|

||||

conv_layer = nn.Conv2d(in_channels=64, out_channels=256, kernel_size=1, padding=0, stride=1)

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

This takes $256\times 1\times 1\times 64 + 64\times 3\times 3\times 64 + 64\times 1\times 1\times 256 = 16,384 + 36,864 + 16,384 = 69,632$ parameters.

|

||||

|

||||

This lose some information, but save a lot of parameters.

|

||||

|

||||

#### Depthwise convolutions

|

||||

|

||||

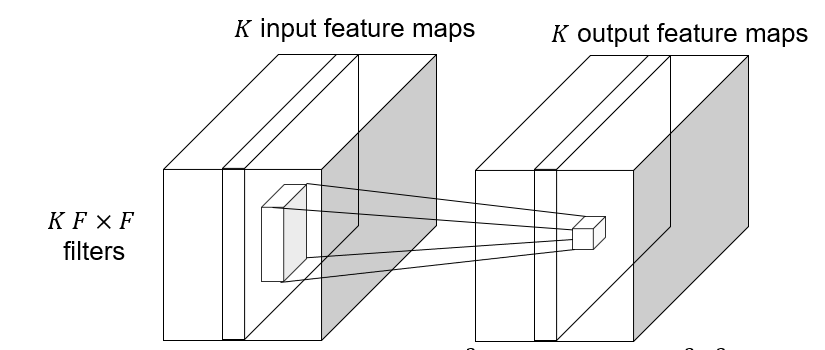

Depthwise convolution: $K\to K$ feature map, save computation, reduce the number of parameters.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

#### Grouped convolutions

|

||||

|

||||

Self defined convolution on the feature map following the similar manner.

|

||||

|

||||

### Backward pass

|

||||

|

||||

Vector-matrix form:

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\frac{\partial e}{\partial x}=\frac{\partial e}{\partial z}\frac{\partial z}{\partial x}

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

Suppose the kernel is 3x3, the feature map is $\ldots, x_{i-1}, x_i, x_{i+1}, \ldots$, and $\ldots, z_{i-1}, z_i, z_{i+1}, \ldots$ is the output feature map, then:

|

||||

|

||||

The convolution operation can be written as:

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

z_i = w_1x_{i-1} + w_2x_i + w_3x_{i+1}

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

The gradient of the kernel is:

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\frac{\partial e}{\partial x_i} = \sum_{j=-1}^{1}\frac{\partial e}{\partial z_i}\frac{\partial z_i}{\partial x_i} = \sum_{j=-1}^{1}\frac{\partial e}{\partial z_i}w_j

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

### Max-pooling

|

||||

|

||||

Get max value in the local region.

|

||||

|

||||

#### Receptive field

|

||||

|

||||

The receptive field of a unit is the region of the input feature map whose values contribute to the response of that unit (either in the previous layer or in the initial image)

|

||||

|

||||

## Architecture of CNNs

|

||||

|

||||

### AlexNet (2012-2013)

|

||||

|

||||

Successor of LeNet-5, but with a few significant changes

|

||||

|

||||

- Max pooling, ReLU nonlinearity

|

||||

- Dropout regularization

|

||||

- More data and bigger model (7 hidden layers, 650K units, 60M params)

|

||||

- GPU implementation (50x speedup over CPU)

|

||||

- Trained on two GPUs for a week

|

||||

|

||||

#### Key points

|

||||

|

||||

Most floating point operations occur in the convolutional layers.

|

||||

|

||||

Most of the memory usage is in the early convolutional layers.

|

||||

|

||||

Nearly all parameters are in the fully-connected layers.

|

||||

|

||||

### VGGNet (2014)

|

||||

|

||||

### GoogLeNet (2014)

|

||||

|

||||

### ResNet (2015)

|

||||

|

||||

### Beyond ResNet (2016 and onward): Wide ResNet, ResNeXT, DenseNet

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

@@ -12,4 +12,5 @@ export default {

|

||||

CSE559A_L7: "Computer Vision (Lecture 7)",

|

||||

CSE559A_L8: "Computer Vision (Lecture 8)",

|

||||

CSE559A_L9: "Computer Vision (Lecture 9)",

|

||||

CSE559A_L10: "Computer Vision (Lecture 10)",

|

||||

}

|

||||

|

||||

@@ -1,4 +1,4 @@

|

||||

# Lecture 1

|

||||

# Math4121 Lecture 1

|

||||

|

||||

## Chapter 5: Differentiation

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

@@ -1,4 +1,4 @@

|

||||

# Lecture 10

|

||||

# Math 4121 Lecture 10

|

||||

|

||||

## Recap

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

@@ -1 +1,103 @@

|

||||

# Lecture 13

|

||||

# Math4121 Lecture 13

|

||||

|

||||

## New book Chapter 2

|

||||

|

||||

Riemann's motivation: Fourier series

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

F(x) = \frac{a_0}{2} + \sum_{k=1}^{\infty} a_k \cos(kx) + b_k \sin(kx)

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

$a_k = \frac{1}{\pi} \int_{-\pi}^{\pi} f(x) \cos(kx) dx$

|

||||

|

||||

$b_k = \frac{1}{\pi} \int_{-\pi}^{\pi} f(x) \sin(kx) dx$

|

||||

|

||||

To study the convergence of the Fourier series, we need to study the convergence of the sequence of partial sums. (Riemann integration)

|

||||

|

||||

Why Riemann integration?

|

||||

|

||||

Let

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

((x)) = \begin{cases}

|

||||

x-\lfloor x \rfloor & x \in [\lfloor x \rfloor, \lfloor x \rfloor + \frac{1}{2}) \\

|

||||

0 & x=\lfloor x \rfloor + \frac{1}{2}\\

|

||||

x-\lfloor x \rfloor - 1 & x \in (\lfloor x \rfloor + \frac{1}{2}, \lfloor x \rfloor + 1] \end{cases}

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

We define

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

f(x) = \sum_{n=1}^{\infty} \frac{((nx))}{n^2}=\lim_{N\to\infty}\sum_{n=1}^{N} \frac{((nx))}{n^2}

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

(i) The series converges uniformly over $x\in[0,1]$.

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\left|f(x)-\sum_{n=1}^{N} \frac{((nx))}{n^2}\right|\leq \sum_{n=N+1}^{\infty}\frac{|((nx))|}{n^2}\leq \sum_{n=N+1}^{\infty} \frac{1}{n^2}<\epsilon

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

As a consequence, $f(x)\in \mathscr{R}$.

|

||||

|

||||

(ii) $f$ has a discontinuity at every rational number with even denominator.

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\begin{aligned}

|

||||

\lim_{h\to 0^+}f(\frac{a}{2b}+h)-f(\frac{a}{2b})&=\lim_{h\to 0^+}\sum_{n=1}^{\infty}\frac{((\frac{na}{2b}+h))}{n^2}-\sum_{n=1}^{\infty}\frac{((\frac{na}{2b}))}{n^2}\\

|

||||

&=\lim_{h\to 0^+}\sum_{n=1}^{\infty}\frac{((\frac{na}{2b}+h))-((\frac{na}{2b}))}{n^2}\\

|

||||

&=\sum_{n=1}^{\infty}\lim_{h\to 0^+}\frac{((\frac{na}{2b}+h))-((\frac{na}{2b}))}{n^2}\\

|

||||

&>0

|

||||

\end{aligned}

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

### Back to the fundamental theorem of calculus

|

||||

|

||||

Suppose $f$ is integrable on $[a,b]$, then

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

F(x)=\int_a^x f(t)dt

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

$F$ is continuous on $[a,b]$.

|

||||

|

||||

if $f$ is continuous at $x_0$, then $F$ is differentiable at $x_0$ and $F'(x_0)=f(x_0)$.

|

||||

|

||||

#### Theorem (Darboux's theorem)

|

||||

|

||||

If $\lim_{x\to a^-}f(x)=L^-$, then $\lim_{h\to 0} \frac{f(a+h)-f(a)}{h}=L^-$.

|

||||

|

||||

Proof:

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

h\sup_{x\in [0,h]}f(x)\geq F(a+h)\geq \inf_{x\in [0,h]}f(x)h

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

Consequently,

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

f(x)=\sum_{n=1}^{\infty} \frac{((nx))}{n^2}

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

then

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

F(x)=\int_0^x f(t)dt

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

is continuous on $[0,1]$.

|

||||

|

||||

However, since $\lim_{x\to 0^+}f(x)\neq \lim_{x\to 0^-}f(x)$ holds for all the rational numbers with even denominator, $F$ is not differentiable at all the rational numbers with even denominator.

|

||||

|

||||

Moral: There exists a continuous function on $[0,1]$ that is not differentiable at any rational number with even denominator. (Dense set)

|

||||

|

||||

#### Weierstrass function

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

g(x)=\sum_{n=0}^{\infty} a^n \cos(b^n \pi x)

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

where $0<a<1$ and $ab>1+\frac{3}{2}\pi$.

|

||||

|

||||

$g(x)$ is continuous on $\mathbb{R}$ but nowhere differentiable.

|

||||

|

||||

_If we change our integral, will be differentiable at most points?_

|

||||

|

||||

@@ -1 +1,19 @@

|

||||

# Lecture 14

|

||||

# Math 4121 Lecture 14

|

||||

|

||||

## Recap

|

||||

|

||||

### Hankel developedn Riemann's integrabilty criterion.

|

||||

|

||||

#### Definition

|

||||

|

||||

Given an interval $I\subset[a,b]$, $f:[a,b]\to\mathbb{R}$ the oscillation of $f$ at $I$ is

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\omega(f,I) = \sup_I f - \inf_I f

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

#### Theorem

|

||||

|

||||

A bounded function $f$ is Riemann integrable if and only if

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

@@ -1,4 +1,4 @@

|

||||

# Lecture 2

|

||||

# Math4121 Lecture 2

|

||||

|

||||

## Chapter 5: Differentiation

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

@@ -1,4 +1,4 @@

|

||||

# Lecture 3

|

||||

# Math4121 Lecture 3

|

||||

|

||||

## Continue on Differentiation

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

@@ -1,4 +1,4 @@

|

||||

# Lecture 4

|

||||

# Math4121 Lecture 4

|

||||

|

||||

## Chapter 5. Differentiation

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

@@ -1,4 +1,4 @@

|

||||

# Lecture 5

|

||||

# Math4121 Lecture 5

|

||||

|

||||

## Continue on differentiation

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

@@ -1,4 +1,4 @@

|

||||

# Lecture 6

|

||||

# Math4121 Lecture 6

|

||||

|

||||

## Chapter 6: Riemann-Stieltjes Integral

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

@@ -1,4 +1,4 @@

|

||||

# Lecture 7

|

||||

# Math4121 Lecture 7

|

||||

|

||||

## Continue on Chapter 6

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

@@ -1,4 +1,4 @@

|

||||

# Lecture 8

|

||||

# Math4121 Lecture 8

|

||||

|

||||

## Continue on Riemann-Stieltjes Integral

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

@@ -1,4 +1,4 @@

|

||||

# Lecture 9

|

||||

# Math 4121 Lecture 9

|

||||

|

||||

Exam next week.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

190

pages/Math416/Math416_L10.md

Normal file

190

pages/Math416/Math416_L10.md

Normal file

@@ -0,0 +1,190 @@

|

||||

# Math416 Lecture 10

|

||||

|

||||

## Fast reload on Power Series

|

||||

|

||||

Suppose $\sum_{n=0}^\infty a_n$ converges absolutely. ($\sum_{n=0}^\infty |a_n|<\infty$)

|

||||

|

||||

Then rearranging the terms of the series does not affect the sum of the series.

|

||||

|

||||

For any permutation $\sigma$ of the set of positive integers, $\sum_{n=0}^\infty a_{\sigma(n)}=\sum_{n=0}^\infty a_n$.

|

||||

|

||||

Proof:

|

||||

|

||||

Let $\epsilon>0$, then $\exists N\in\mathbb{N}$ such that $\forall n\geq N$,

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\sum_{n=N}^\infty |a_n|<\epsilon

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

So there exists $N_0$ such that if $M\geq N_0$, then

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\sum_{n=N_0}^M |a_n|<\epsilon

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

_for any first $M$ terms of $\sigma$, we choose $N_0$ such that all the terms (no overlapping with the first $M$ terms) on the tail is less than $\epsilon$_.

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\sum_{n=1}^{\infty} a_n=\sum_{n=1}^{M} a_n+\sum_{n=M+1}^\infty a_n

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

Let $K>N$, $L>N_0$,

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\left|\sum_{n=1}^{K}a_n-\sum_{n=1}^{L}a_{\sigma(n)}\right|<2\epsilon

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

EOP

|

||||

|

||||

## Chapter 4 Complex Integration

|

||||

|

||||

### Complex Integral

|

||||

|

||||

#### Definition 4.1

|

||||

|

||||

If $\phi(t)$ is a complex function defined on $[a,b]$, then the integral of $\phi(t)$ over $[a,b]$ is defined as

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\int_a^b \phi(t) dt = \int_a^b \text{Re}\{\phi(t)\} dt + i\int_a^b \text{Im}\{\phi(t)\} dt

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

#### Theorem 4.3 (Triangle Inequality)

|

||||

|

||||

If $\phi(t)$ is a complex function defined on $[a,b]$, then

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\left|\int_a^b \phi(t) dt\right| \leq \int_a^b |\phi(t)| dt

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

Proof:

|

||||

|

||||

Let $\lambda(t)=\frac{\left|\int_a^t \phi(t) dt\right|}{\int_a^t |\phi(t)| dt}$, then $\left|\lambda(t)\right|=1$.

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\begin{aligned}

|

||||

\left|\int_a^b \phi(t) dt\right|&=\lambda\int_a^b \phi(t) dt\\

|

||||

&=\int_a^b \lambda(t)\phi(t) dt\\

|

||||

&=\text{Re} \{\int_a^b \lambda(t)\phi(t) dt\}\\

|

||||

&\leq\int_a^b |\lambda(t)\phi(t)| dt\\

|

||||

&=\int_a^b |\phi(t)| dt

|

||||

\end{aligned}

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

Assume $\phi$ is continuous on $[a,b]$, the equality means $\lambda(t)\phi(t)$ is real and positive everywhere on $[a,b]$, which means $\arg \phi(t)$ is constant.

|

||||

|

||||

EOP

|

||||

|

||||

#### Definition 4.4 Arc Length

|

||||

|

||||

Let $\gamma$ be a curve in the complex plane defined by $\gamma(t)=x(t)+iy(t)$, $t\in[a,b]$. The arc length of $\gamma$ is given by

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\Gamma=\int_a^b |\gamma'(t)| dt=\int_a^b \sqrt{\left(\frac{dx}{dt}\right)^2+\left(\frac{dy}{dt}\right)^2} dt

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

N.B. If $\int_{\Gamma} f(\zeta) d\zeta$ depends on orientation of $\Gamma$, but not the parametrization.

|

||||

|

||||

We define

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\int_{\Gamma} f(\zeta) d\zeta=\int_{\Gamma} f(\gamma(t))\gamma'(t) dt

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

Example:

|

||||

|

||||

Suppose $\Gamma$ is the circle centered at $z_0$ with radius $R$

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\int_{\Gamma} \frac{1}{\zeta-z_0} d\zeta

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

Parameterize the unit circle:

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\gamma(t)=z_0+Re^{it}\quad

|

||||

\gamma'(t)=iRe^{it}, t\in[0,2\pi]

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

f(\zeta)=\frac{1}{\zeta-z_0}

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

f(\gamma(t))=\frac{1}{(z_0+Re^{it})-z_0}

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\int_{\Gamma} f(\zeta) d\zeta=\int_0^{2\pi} f(\gamma(t))\gamma'(t) dt=\int_0^{2\pi} \frac{1}{Re^{-it}}iRe^{it} dt=2\pi i

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

#### Theorem 4.11 (Uniform Convergence)

|

||||

|

||||

If $f_n(z)$ converges uniformly to $f(z)$ on $\Gamma$, assume length of $\Gamma$ is finite, then

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\lim_{n\to\infty} \int_{\Gamma} f_n(z) dz = \int_{\Gamma} f(z) dz

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

Proof:

|

||||

|

||||

Let $\epsilon>0$, since $f_n(z)$ converges uniformly to $f(z)$ on $\Gamma$, there exists $N\in\mathbb{N}$ such that for all $n\geq N$,

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\left|f_n(z)-f(z)\right|<\epsilon

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\begin{aligned}

|

||||

\left|\int_{\Gamma} f_n(z) dz - \int_{\Gamma} f(z) dz\right|&=\left|\int_{\Gamma} (f_n(\gamma(t))-f(\gamma(t)))\gamma'(t) dt\right|\\

|

||||

&\leq \int_{\Gamma} |f_n(\gamma(t))-f(\gamma(t))||\gamma'(t)| dt\\

|

||||

&\leq \int_{\Gamma} \epsilon|\gamma'(t)| dt\\

|

||||

&=\epsilon\text{length}(\Gamma)

|

||||

\end{aligned}

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

EOP

|

||||

|

||||

#### Theorem 4.6 (Integral of derivative)

|

||||

|

||||

Suppose $\Gamma$ is a closed curve, $\gamma:[a,b]\to\mathbb{C}$ and $\gamma(a)=\gamma(b)$.

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\begin{aligned}

|

||||

\int_{\Gamma} f'(z) dz &= \int_a^b f'(\gamma(t))\gamma'(t) dt\\

|

||||

&=\int_a^b \frac{d}{dt}f(\gamma(t)) dt\\

|

||||

&=f(\gamma(b))-f(\gamma(a))\\

|

||||

&=0

|

||||

\end{aligned}

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

EOP

|

||||

|

||||

Example:

|

||||

|

||||

Let $R$ be a rectangle $\{-a,a,ai+b,ai-b\}$, $\Gamma$ is the boundary of $R$ with positive orientation.

|

||||

|

||||

Let $\int_{R} e^{-\zeta^2}d\zeta$.

|

||||

|

||||

Is $e^{-\zeta^2}=\frac{d}{d\zeta}f(\zeta)$?

|

||||

|

||||

Yes, since

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

e^{\zeta^2}=1-\frac{\zeta^2}{1!}+\frac{\zeta^4}{2!}-\frac{\zeta^6}{3!}+\cdots=\frac{d}{d\zeta}\left(\frac{\zeta}{1!}-\frac{1}{3}\frac{\zeta^3}{2!}+\frac{1}{5}\frac{\zeta^5}{3!}-\cdots\right)

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

This is polynomial, therefore holomorphic.

|

||||

|

||||

So

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\int_{R} e^{\zeta^2}d\zeta = 0

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

with some limit calculation, we can get

|

||||

|

||||

<!--TODO: Fill the parts-->

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\int_{R} e^{-\zeta^2}d\zeta = 2\pi i

|

||||

$$

|

||||

@@ -1,4 +1,4 @@

|

||||

# Lecture 3

|

||||

# Math416 Lecture 3

|

||||

|

||||

## Differentiation of functions in complex variables

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

@@ -1,4 +1,4 @@

|

||||

# Lecture 4

|

||||

# Math416 Lecture 4

|

||||

|

||||

## Review

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

@@ -1,4 +1,4 @@

|

||||

# Lecture 5

|

||||

# Math416 Lecture 5

|

||||

|

||||

## Review

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

@@ -1,4 +1,4 @@

|

||||

# Lecture 6

|

||||

# Math416 Lecture 6

|

||||

|

||||

## Review

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

@@ -1,4 +1,4 @@

|

||||

# Lecture 7

|

||||

# Math416 Lecture 7

|

||||

|

||||

## Review

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

@@ -1,4 +1,4 @@

|

||||

# Lecture 8

|

||||

# Math416 Lecture 8

|

||||

|

||||

## Review

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

@@ -11,5 +11,6 @@ export default {

|

||||

Math416_L6: "Complex Variables (Lecture 6)",

|

||||

Math416_L7: "Complex Variables (Lecture 7)",

|

||||

Math416_L8: "Complex Variables (Lecture 8)",

|

||||

Math416_L9: "Complex Variables (Lecture 9)"

|

||||

Math416_L9: "Complex Variables (Lecture 9)",

|

||||

Math416_L10: "Complex Variables (Lecture 10)",

|

||||

}

|

||||

|

||||

@@ -2,4 +2,4 @@

|

||||

|

||||

This is a course about symmetrical group and bunch of applications in other fields of math.

|

||||

|

||||

Prof. Fere is teaching this course.

|

||||

Prof. Renado Fere is teaching this course.

|

||||

|

||||

Reference in New Issue

Block a user