seems working on this small batch

This commit is contained in:

@@ -1,264 +0,0 @@

|

||||

# Math4121 Exam 1 Review

|

||||

|

||||

Range: Chapter 5 and 6 of Rudin. We skipped (and so you will not be tested on)

|

||||

|

||||

- Differentiation of Vector Valued Functions (pp. 111-113)

|

||||

- Integration of Vector-Valued Function and Rectifiable Curves (pp.135-137)

|

||||

|

||||

You will also not be tested on Uniform Convergence and Integration, which we cover in class on Monday 2/10.

|

||||

|

||||

## Chapter 5: Differentiation

|

||||

|

||||

### Definition of the Derivative

|

||||

|

||||

Let $f$ be a real function defined on an closed interval $[a,b]$. We say that $f$ is differentiable at a point $x \in [a,b]$ if the following limit exists:

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

f'(x) = \lim_{t\to x} \frac{f(t) - f(x)}{t - x}

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

If the limit exists, we call it the derivative of $f$ at $x$ and denote it by $f'(x)$.

|

||||

|

||||

#### Theorem 5.2

|

||||

|

||||

Every differentiable function is [continuous](https://notenextra.trance-0.com/Math4111/Math4111_L22#definition-45).

|

||||

|

||||

The converse is not true, consider $f(x) = |x|$.

|

||||

|

||||

#### Theorem 5.3

|

||||

|

||||

If $f,g$ are differentiable at $x$, then

|

||||

|

||||

1. $(f+g)'(x) = f'(x) + g'(x)$

|

||||

2. $(fg)'(x) = f'(x)g(x) + f(x)g'(x)$

|

||||

3. If $g(x) \neq 0$, then $(f/g)'(x) = (f'(x)g(x) - f(x)g'(x))/g(x)^2$

|

||||

|

||||

#### Theorem 5.4

|

||||

|

||||

Constant function is differentiable and its derivative is $0$.

|

||||

|

||||

#### Theorem 5.5

|

||||

|

||||

Chain rule: If $f$ is differentiable at $x$ and $g$ is differentiable at $f(x)$, then the composite function $g\circ f$ is differentiable at $x$ and

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

(g\circ f)'(x) = g'(f(x))f'(x)

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

#### Theorem 5.8

|

||||

|

||||

The derivative of local extremum ($\exists \delta > 0$ s.t. $f(x)\geq f(y)$ or $f(x)\leq f(y)$ for all $y\in (x-\delta,x+\delta)$) is $0$.

|

||||

|

||||

#### Theorem 5.9

|

||||

|

||||

Generalized mean value theorem: If $f,g$ are differentiable on $(a,b)$, then there exists a point $x\in (a,b)$ such that

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

(f(b)-f(a))g'(x) = (g(b)-g(a))f'(x)

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

If we put $g(x) = x$, we get the mean value theorem.

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

f(b)-f(a) = f'(x)(b-a)

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

for some $x\in (a,b)$.

|

||||

|

||||

#### Theorem 5.12

|

||||

|

||||

Intermediate value theorem:

|

||||

|

||||

If $f$ is differentiable on $[a,b]$, for all $\lambda$ between $f'(a)$ and $f'(b)$, there exists a $c\in (a,b)$ such that $f'(x) = \lambda$.

|

||||

|

||||

#### Theorem 5.13

|

||||

|

||||

L'Hôpital's rule: If $f,g$ are differentiable in $(a,b)$ and $g'(x) \neq 0$ for all $x\in (a,b)$, where $-\infty \leq a < b \leq \infty$,

|

||||

|

||||

Suppose

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\frac{f'(x)}{g'(x)} \to A \text{ as } x\to a

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

If

|

||||

$$

|

||||

f(x) \to 0, g(x) \to 0 \text{ as } x\to a

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

or if

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

g(x) \to \infty \text{ as } x\to a

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

then

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\lim_{x\to a} \frac{f(x)}{g(x)} = A

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

#### Theorem 5.15

|

||||

|

||||

Taylor's theorem: If $f$ is $n$ times differentiable on $[a,b]$, $f^{(n-1)}$ is continuous on $[a,b]$, and $f^{(n)}$ exists on $(a,b)$, for any distinct points $\alpha, \beta \in [a,b]$, there exists a point $x\in (\alpha, \beta)$ such that

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

f(\beta) =\left(\sum_{k=0}^{n-1} \frac{f^{(k)}(\alpha)}{k!}(\beta-\alpha)^k\right) + \frac{f^{(n)}(x)}{n!}(\beta-\alpha)^n

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

## Chapter 6: Riemann-Stieltjes Integration

|

||||

|

||||

### Definition of the Integral

|

||||

|

||||

Let $\alpha$ be a monotonically increasing function on $[a,b]$.

|

||||

|

||||

A partition of $[a,b]$ is a set of points $P = \{x_0, x_1, \cdots, x_n\}$ such that

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

a = x_0 < x_1 < \cdots < x_n = b

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

Let $\Delta \alpha_i = \alpha(x_{i}) - \alpha(x_{i-1})$ for $i = 1, \cdots, n$.

|

||||

|

||||

Let $m_i = \inf \{f(x) : x_{i-1} \leq x \leq x_{i}\}$ and $M_i = \sup \{f(x) : x_{i-1} \leq x \leq x_{i}\}$ for $i = 1, \cdots, n$.

|

||||

|

||||

The lower sum of $f$ with respect to $\alpha$ is

|

||||

|

||||

$$L(f,P,\alpha) = \sum_{i=1}^{n} m_i \Delta \alpha_i$$

|

||||

|

||||

The upper sum of $f$ with respect to $\alpha$ is

|

||||

|

||||

$$U(f,P,\alpha) = \sum_{i=1}^{n} M_i \Delta \alpha_i$$

|

||||

|

||||

Let $\overline{\int_a^b} f(x) d\alpha(x)=\sup_P L(f,P,\alpha)$ and $\underline{\int_a^b} f(x) d\alpha(x)=\inf_P U(f,P,\alpha)$.

|

||||

|

||||

If $\overline{\int_a^b} f(x) d\alpha(x) = \underline{\int_a^b} f(x) d\alpha(x)$, we say that $f$ is Riemann-Stieltjes integrable with respect to $\alpha$ on $[a,b]$ and we write

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\int_a^b f(x) d\alpha(x) = \overline{\int_a^b} f(x) d\alpha(x) = \underline{\int_a^b} f(x) d\alpha(x)

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

#### Theorem 6.4

|

||||

|

||||

Refinement of partition will never make the lower sum smaller or the upper sum larger.

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

L(f,P,\alpha) \leq L(f,P^*,\alpha) \leq U(f,P^*,\alpha) \leq U(f,P,\alpha)

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

#### Theorem 6.5

|

||||

|

||||

$\underline{\int_a^b} f(x) d\alpha(x) \leq \overline{\int_a^b} f(x) d\alpha(x)$

|

||||

|

||||

#### Theorem 6.6

|

||||

|

||||

$f\in \mathscr{R}(\alpha)$ on $[a,b]$ if and only if for every $\epsilon > 0$, there exists a partition $P$ of $[a,b]$ such that

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

U(f,P,\alpha) - L(f,P,\alpha) < \epsilon

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

#### Theorem 6.8

|

||||

|

||||

Every continuous function on a closed interval is Riemann-Stieltjes integrable with respect to any monotonically increasing function.

|

||||

|

||||

#### Theorem 6.9

|

||||

|

||||

If $f$ is monotonically increasing on $[a,b]$ and **$\alpha$ is continuous on $[a,b]$**, then $f\in \mathscr{R}(\alpha)$ on $[a,b]$.

|

||||

|

||||

Key: We can repartition the interval $[a,b]$ using $f$.

|

||||

|

||||

#### Theorem 6.10

|

||||

|

||||

If $f$ is bounded on $[a,b]$ and has only **finitely many discontinuities** on $[a,b]$, then $f\in \mathscr{R}(\alpha)$ on $[a,b]$.

|

||||

|

||||

Key: We can use the bound and partition around the points of discontinuity to make the error arbitrary small.

|

||||

|

||||

#### Theorem 6.11

|

||||

|

||||

If $f\in \mathscr{R}(\alpha)$ on $[a,b]$, and $m\leq f(x) \leq M$ for all $x\in [a,b]$, and $\phi$ is a continuous function on $[m,M]$, then $\phi\circ f\in \mathscr{R}(\alpha)$ on $[a,b]$.

|

||||

|

||||

_Composition of bounded integrable functions and continuous functions is integrable._

|

||||

|

||||

#### Theorem 6.12

|

||||

|

||||

Properties of the integral:

|

||||

|

||||

Let $f,g\in \mathscr{R}(\alpha)$ on $[a,b]$, and $c$ be a constant. Then

|

||||

|

||||

1. $f+g\in \mathscr{R}(\alpha)$ on $[a,b]$ and $\int_a^b (f(x) + g(x)) d\alpha(x) = \int_a^b f(x) d\alpha(x) + \int_a^b g(x) d\alpha(x)$

|

||||

2. $cf\in \mathscr{R}(\alpha)$ on $[a,b]$ and $\int_a^b cf(x) d\alpha(x) = c\int_a^b f(x) d\alpha(x)$

|

||||

3. $f\in \mathscr{R}(\alpha)$ on $[a,b]$ and $c\in [a,b]$, then $\int_a^b f(x) d\alpha(x) = \int_a^c f(x) d\alpha(x) + \int_c^b f(x) d\alpha(x)$.

|

||||

4. **Favorite Estimate**: If $|f(x)| \leq M$ for all $x\in [a,b]$, then $\left|\int_a^b f(x) d\alpha(x)\right| \leq M(\alpha(b)-\alpha(a))$.

|

||||

5. If $f\in \mathscr{R}(\beta)$ on $[a,b]$, then $\int_a^b f(x) d(\alpha+\beta) = \int_a^b f(x) d\alpha + \int_a^b f(x) d\beta$.

|

||||

|

||||

#### Theorem 6.13

|

||||

|

||||

If $f,g\in \mathscr{R}(\alpha)$ on $[a,b]$, then

|

||||

|

||||

1. $fg\in \mathscr{R}(\alpha)$ on $[a,b]$

|

||||

2. $|f|\in \mathscr{R}(\alpha)$ on $[a,b]$ and $\left|\int_a^b f(x) d\alpha(x)\right| \leq \int_a^b |f(x)| d\alpha(x)$

|

||||

|

||||

Key: (1), use Theorem 6.12, 6.11 to build up $fg$ from $(f+g)^2-f^2-g^2$. (2), take $\phi(x) = |x|$ in Theorem 6.11.

|

||||

|

||||

#### Theorem 6.14

|

||||

|

||||

Integration over indicator functions:

|

||||

|

||||

If $a<s<b$, $f$ is bounded on $[a,b]$, and $f$ is continuous at $s$, and $\alpha(x)=I(x-s)$, then

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\int_a^b f(x) d\alpha(x) = f(s)

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

Key: Note the max difference can be made only occurs at $s$.

|

||||

|

||||

#### Theorem 6.15

|

||||

|

||||

Integration over step functions:

|

||||

|

||||

If $\alpha(x) = \sum_{i=1}^{n} c_i I(x-x_i)$ for $x\in [a,b]$, then

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\int_a^b f(x) d\alpha(x) = \sum_{i=1}^{n} c_i f(x_i)

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

#### Theorem 6.21

|

||||

|

||||

Fundamental theorem of calculus:

|

||||

|

||||

Let $f\in \mathscr{R}(\alpha)$ on $[a,b]$, and $F(x) = \int_a^x f(t) d\alpha(t)$. Then

|

||||

|

||||

1. $F$ is continuous on $[a,b]$

|

||||

2. If $f$ is continuous at $x\in [a,b]$, then $F$ is differentiable at $x$ and $F'(x) = f(x)$

|

||||

|

||||

## Chapter 7: Sequence and Series of Functions

|

||||

|

||||

### Example of non-Riemann integrable function

|

||||

|

||||

$\lim_{m\to \infty} \lim_{n\to \infty} (\cos(m!\pi x))^{2n}=\begin{cases} 1 & x\in \mathbb{Q} \\ 0 & x\notin \mathbb{Q} \end{cases}$

|

||||

|

||||

This function is everywhere discontinuous and not Riemann integrable.

|

||||

|

||||

### Uniform Convergence

|

||||

|

||||

#### Definition 7.7

|

||||

|

||||

A sequence of functions $\{f_n\}$ converges uniformly to $f$ on $E$ if for every $\epsilon > 0$, there exists a positive integer $N$ such that

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|f_n(x) - f(x)| < \epsilon \text{ for all } x\in E \text{ and } n\geq N

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

If $E$ is a point, then that's the common definition of convergence.

|

||||

|

||||

If we have uniform convergence, then we can swap the order of limits.

|

||||

|

||||

#### Theorem 7.16

|

||||

|

||||

If $\{f_n\}\in \mathscr{R}(\alpha)$ on $[a,b]$, and $\{f_n\}$ converges uniformly to $f$ on $[a,b]$, then

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\int_a^b f(x) d\alpha(x) = \lim_{n\to \infty} \int_a^b f_n(x) d\alpha(x)

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

Key: Use the definition of uniform convergence to bound the difference between the integral of the limit and the limit of the integral. $\int_a^b (f-f_n)d\alpha \leq |f-f_n| \int_a^b d\alpha = |f-f_n| (\alpha(b)-\alpha(a))$.

|

||||

@@ -1,279 +0,0 @@

|

||||

# Math4121 Exam 2 Review

|

||||

|

||||

Range: Chapter 2-4 of Bressoud's A Radical Approach to Lebesgue's Theory of Integration

|

||||

|

||||

## Chapter 2

|

||||

|

||||

### The Riemann-Stieltjes Integral

|

||||

|

||||

#### Definition of the Riemann-Stieltjes Integral

|

||||

|

||||

Let $f$ be a bounded function on $[a,b]$ and $\alpha$ be a bounded function on $[a,b]$.

|

||||

|

||||

We say that $f$ is Riemann-Stieltjes integrable with respect to $\alpha$ on $[a,b]$ if there exists a number $I$ such that for every $\epsilon > 0$, there exists a $\delta > 0$ such that for every partition $P = \{a = x_0, x_1, \ldots, x_n = b\}$ of $[a,b]$ with $||P|| < \delta$, we have

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\left| \int_a^b f \, d\alpha - I \right| < \epsilon

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

If $f$ is Riemann-Stieltjes integrable with respect to $\alpha$ on $[a,b]$, we write

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\int_a^b f \, d\alpha = I

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

#### Darboux Sums

|

||||

|

||||

Let $P = \{a = x_0, x_1, \ldots, x_n = b\}$ be a partition of $[a,b]$.

|

||||

|

||||

The upper Darboux sum of $f$ with respect to $\alpha$ is

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

U(f, \alpha, P) = \sum_{i=1}^n M_i (x_i - x_{i-1})

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

where $M_i = \sup_{x \in [x_{i-1}, x_i]} f(x)$ and $\alpha_i = \sup_{x \in [x_{i-1}, x_i]} \alpha(x)$.

|

||||

|

||||

The lower Darboux sum of $f$ with respect to $\alpha$ is

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

L(f, \alpha, P) = \sum_{i=1}^n m_i (x_i - x_{i-1})

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

where $m_i = \inf_{x \in [x_{i-1}, x_i]} f(x)$ and $\alpha_i = \inf_{x \in [x_{i-1}, x_i]} \alpha(x)$.

|

||||

|

||||

### Fail of Riemann-Stieltjes Integration

|

||||

|

||||

Consider the function

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

((x)) = \begin{cases}

|

||||

x-\lfloor x \rfloor & x \in [\lfloor x \rfloor, \lfloor x \rfloor + \frac{1}{2}) \\

|

||||

0 & x=\lfloor x \rfloor + \frac{1}{2}\\

|

||||

x-\lfloor x \rfloor - 1 & x \in (\lfloor x \rfloor + \frac{1}{2}, \lfloor x \rfloor + 1] \end{cases}

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

).png)

|

||||

|

||||

We define

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

f(x) = \sum_{n=1}^{\infty} \frac{((nx))}{n^2}=\lim_{N\to\infty}\sum_{n=1}^{N} \frac{((nx))}{n^2}

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

).png)

|

||||

|

||||

(i) The series converges uniformly over $x\in[0,1]$.

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\left|f(x)-\sum_{n=1}^{N} \frac{((nx))}{n^2}\right|\leq \sum_{n=N+1}^{\infty}\frac{|((nx))|}{n^2}\leq \sum_{n=N+1}^{\infty} \frac{1}{n^2}<\epsilon

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

As a consequence, $f(x)\in \mathscr{R}$.

|

||||

|

||||

(ii) $f$ has a discontinuity at every rational number with even denominator.

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\begin{aligned}

|

||||

\lim_{h\to 0^+}f(\frac{a}{2b}+h)-f(\frac{a}{2b})&=\lim_{h\to 0^+}\sum_{n=1}^{\infty}\frac{((\frac{na}{2b}+h))}{n^2}-\sum_{n=1}^{\infty}\frac{((\frac{na}{2b}))}{n^2}\\

|

||||

&=\lim_{h\to 0^+}\sum_{n=1}^{\infty}\frac{((\frac{na}{2b}+h))-((\frac{na}{2b}))}{n^2}\\

|

||||

&=\sum_{n=1}^{\infty}\lim_{h\to 0^+}\frac{((\frac{na}{2b}+h))-((\frac{na}{2b}))}{n^2}\\

|

||||

&>0

|

||||

\end{aligned}

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

#### Some integrable functions are not differentiable (violates the fundamental theorem of calculus)

|

||||

|

||||

Solve:

|

||||

|

||||

Define the oscilation of $f$ on $[x_{i-1}, x_i]$ as

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\omega(f, [x_{i-1}, x_i]) = \sup_{x,y \in [x_{i-1}, x_i]} |f(x) - f(y)|-\inf_{x,y \in [x_{i-1}, x_i]} |f(x) - f(y)|

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

And define continuous functions as those functions that have oscilation 0 on every subinterval of their domain.

|

||||

|

||||

that is, the function $f$ is continuous at $c$ if $\omega(f,c) = 0$.

|

||||

|

||||

And we claim that the function is integrable on $[a,b]$ if and only if the outer measure of the set of discontinuities of $f$ is 0.

|

||||

|

||||

> Finite cover:

|

||||

>

|

||||

> Given a set $S$, an **finite cover** of $S$ is a **finite** collection of open/ or closed/ or half-open intervals $\{I_1, I_2, \ldots, I_n\}$ such that $S \subseteq \bigcup_{i=1}^n I_i$. The set of all finite covers of $S$ is denoted by $\mathcal{C}_S$.

|

||||

|

||||

> Length of a cover:

|

||||

>

|

||||

> The **length** of a cover $\ell(C)$ is the sum of the lengths of the intervals in the cover. (open/closed/half-open doesn't matter.)

|

||||

|

||||

> Outer content:

|

||||

>

|

||||

> The **outer content** of a set $S$ is the infimum of the lengths of all **finite covers** of $S$. $c_e(S) = \inf_{C\in \mathcal{C}_S}\ell(C)$. (e denotes "exterior")

|

||||

|

||||

Homework question: You cannot cover an interval $[a,b]$ with length $k$ with a finite cover of length strictly less than $k$.

|

||||

|

||||

Proceed by counting the intervals $I_i = [l_i, r_i]$ in the cover, and $r_n-l_0$ is less than or equal to $c_e(S)$ and $l_0\leq a$ and $r_n\leq b$.

|

||||

|

||||

#### Theorem 2.5

|

||||

|

||||

Given a bounded function $f$ defined on the interval $[a,b]$, let $S_\sigma$ be the points in $[a,b]$ with oscilation greater than $\sigma$.

|

||||

|

||||

The function $f$ is Riemann-Stieltjes integrable over $[a,b]$ if and only if $\lim_{\sigma \to 0} |S_\sigma| = 0$. That is, for every $\sigma > 0$, the outer content of $S_\sigma$ is 0.

|

||||

|

||||

Extra terminology:

|

||||

|

||||

> Dense:

|

||||

>

|

||||

> A set $S$ is **dense** in the interval $I$ is every open subinterval of $I$ contains a point of $S$.

|

||||

>

|

||||

> This is equivalent to saying that $S$ is dense in $I$ if every point of $I$ is a limit point of $S$ or a point of $S$. (proved in homework)

|

||||

|

||||

> Totally discontinuous:

|

||||

>

|

||||

> A discontinuous function is **totally discontinuous** in an interval if the set of points of continuity is not dense in that interval.

|

||||

>

|

||||

> In other words, there exists an open interval $I$ such that the set of points of continuity of $f$ in $I$ is empty.

|

||||

|

||||

> Pointwise discontinuity:

|

||||

>

|

||||

> A discontinuous function is **pointwise discontinuous** if the set of points of discontinuity is dense in the domain of $f$.

|

||||

|

||||

> Accumulation point (limit point):

|

||||

>

|

||||

> A point $p$ is an **accumulation point** of a set $S$ if every neighborhood of $p$ contains a point of $S$ other than $p$ itself. (That is, there exists a convergent sequence $\{p_n\}_{n=1}^\infty$ in $S$ such that $\lim_{n\to\infty} p_n = p$ and $p_n \neq p$ for all $n \in \mathbb{N}$. Proved in Rudin)

|

||||

|

||||

> Derived set:

|

||||

>

|

||||

> The **derived set** of a set $S$ is the set of all accumulation points of $S$. $S' = \{p \in \mathbb{R} \mid \forall \epsilon > 0, \exists x \in S \text{ s.t. } 0 < |x-p| < \epsilon\}$.

|

||||

|

||||

> Type 1 set:

|

||||

>

|

||||

> A set $S$ is a **type 1 set** if $S'\neq \emptyset$ and $S''=\emptyset$.

|

||||

|

||||

> Type $n$ set:

|

||||

>

|

||||

> A set $S$ is a **type $n$ set** if $S'$ is a type $n-1$ set.

|

||||

|

||||

> First species:

|

||||

>

|

||||

> A set $S$ is of **first species** if it is type $n$ for some $n\geq 0$, otherwise it is of **second species**.

|

||||

|

||||

$\mathbb{Q}$ is not first species since it is dense in $\mathbb{R}$ and $\mathbb{Q}' = \mathbb{R}$.

|

||||

|

||||

$\mathbb{R}$ is not first species.

|

||||

|

||||

## Chapter 3

|

||||

|

||||

### Topology of $\mathbb{R}$

|

||||

|

||||

> Open set:

|

||||

>

|

||||

> A set $S$ is **open** if for every $x \in S$, there exists an $\epsilon > 0$ such that $B_\epsilon(x) \subseteq S$.

|

||||

|

||||

> Closed set:

|

||||

>

|

||||

> A set $S$ is **closed** if its complement is open.

|

||||

>

|

||||

> Equivalently, a set $S$ is closed if it contains all of its limit points. That is $S' \subseteq S$.

|

||||

|

||||

> Interior of a set:

|

||||

>

|

||||

> The **interior** of a set $S$ is the set of all points in $S$ such that there exists an $\epsilon > 0$ such that $B_\epsilon(x) \subseteq S$. $S^\circ = \{x \in S \mid \exists \epsilon > 0 \text{ s.t. } B_\epsilon(x) \subseteq S\}$. (It is also the union of all open sets contained in $S$.)

|

||||

|

||||

> Closure of a set:

|

||||

>

|

||||

> The **closure** of a set $S$ is the set of all points that for every $\epsilon > 0$, $B_\epsilon(x) \cap S \neq \emptyset$. $\overline{S} = \{x \in \mathbb{R} \mid \forall \epsilon > 0, B_\epsilon(x) \cap S \neq \emptyset\}$.

|

||||

|

||||

> Boundary of a set:

|

||||

>

|

||||

> The **boundary** of a set $S$ is the set of all points in $S$ that are not in the interior of $S$. $\partial S = \overline{S} \setminus S^\circ$.

|

||||

|

||||

#### Theorem 3.4

|

||||

|

||||

Bolzano-Weierstrass Theorem:

|

||||

|

||||

Every bounded infinite set has an accumulation point.

|

||||

|

||||

Proof:

|

||||

|

||||

Let $S$ be a bounded infinite set. Cut the interval $[a,b]$ into two halves, and let $I_1$ be one with infinitely many points of $S$. (such set exists since $S$ is infinite.)

|

||||

|

||||

Let $I_2$ be the one half with infinitely many points of $I_1$.

|

||||

|

||||

By induction, we can cut the interval into two halves, and let $I_{n+1}$ be the one half with infinitely many points of $I_n$.

|

||||

|

||||

By the nested interval property, there exists a point $c$ that is in all $I_n$.

|

||||

|

||||

$c$ is an accumulation point of $S$.

|

||||

|

||||

QED

|

||||

|

||||

#### Theorem 3.6 (Heine-Borel Theorem)

|

||||

|

||||

For any open cover of a compact set, there exists a finite subcover.

|

||||

|

||||

> Compact set:

|

||||

>

|

||||

> A set $S$ is **compact** if every open cover of $S$ has a finite subcover. In $\mathbb{R}$, this is equivalent to being closed and bounded.

|

||||

|

||||

> Cardinality:

|

||||

>

|

||||

> The **cardinality** of $\mathbb{R}$ is $\mathfrak{c}$.

|

||||

>

|

||||

> The **cardinality** of $\mathbb{N}$, $\mathbb{Z}$, and $\mathbb{Q}$ is $\aleph_0$.

|

||||

|

||||

## Chapter 4

|

||||

|

||||

### Nowhere Dense set

|

||||

|

||||

A set $S$ is **nowhere dense** if there are no open intervals in which $S$ is dense.

|

||||

|

||||

That is equivalent to **$S'$ contains no open intervals**.

|

||||

|

||||

Note: If $S$ is nowhere dense, then $S^c$ is dense. But if $S$ is dense, $S^c$ is not necessarily nowhere dense. (Consider $\mathbb{Q}$)

|

||||

|

||||

### Perfect Set

|

||||

|

||||

A set $S$ is **perfect** if $S'=S$.

|

||||

|

||||

Example: open intervals, Cantor set.

|

||||

|

||||

#### Cantor set

|

||||

|

||||

The Cantor set ($SVC(3)$) is the set of all real numbers in $[0,1]$ that can be represented in base 3 using only the digits 0 and 2.

|

||||

|

||||

The outer content of the Cantor set is 0.

|

||||

|

||||

#### Generalized Cantor set (SVC(n))

|

||||

|

||||

The outer content of $SVC(n)$ is $\frac{n-3}{n-2}$.

|

||||

|

||||

#### Lemma 4.4

|

||||

|

||||

Osgood's Lemma:

|

||||

|

||||

Let $G$ be a closed, bounded set and Let $G_1\subseteq G_2\subseteq \ldots$ and $G=\bigcup_{n=1}^{\infty} G_n$. Then $\lim_{n\to\infty} c_e(G_n)=c_e(G)$.

|

||||

|

||||

Key: Using Heine-Borel Theorem.

|

||||

|

||||

#### Theorem 4.5

|

||||

|

||||

Arzela-Osgood Theorem:

|

||||

|

||||

Let $\{f_n\}_{n=1}^{\infty}$ be a sequence of continuous, uniformly bounded functions on $[0,1]$ that converges pointwise to $0$. It follows that

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\lim_{n\to\infty}\int_0^1 f_n(x) \, dx = \int_0^1 \lim_{n\to\infty} f_n(x) \, dx=0

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

Key: Using Osgood's Lemma and do case analysis on bounded and unbounded parts of the Riemann-Stieltjes integral.

|

||||

|

||||

#### Theorem 4.7

|

||||

|

||||

Baire Category Theorem:

|

||||

|

||||

An open interval cannot be covered by a countable union of nowhere dense sets.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

@@ -1,370 +0,0 @@

|

||||

# Math4121 Final Review

|

||||

|

||||

## Guidelines

|

||||

|

||||

There is one question from Exam 2 material.

|

||||

|

||||

3 T/F from Exam 1 material.

|

||||

|

||||

The remaining questions cover the material since Exam 2 (Chapters 5 and 6 of Bressoud and my lecture notes for the final week).

|

||||

|

||||

The format of the exam is quite similar to Exam 2, maybe a tad longer (but not twice as long, don't worry).

|

||||

|

||||

## Chapter 5: Measure Theory

|

||||

|

||||

### Jordan Measure

|

||||

|

||||

> Content

|

||||

>

|

||||

> Let $\mathcal{C}_S^e$ be the set of all finite covers of $S$ by closed intervals ($S\subset C$, where $C$ is a finite union of closed intervals).

|

||||

>

|

||||

> Let $\mathcal{C}_S^i$ be the set of disjoint intervals that contained in $S$ ($\bigcup_{i=1}^n I_i\subset S$, where $I_i$ are disjoint intervals).

|

||||

>

|

||||

> Let $c_e(S)=\sup_{C\in\mathcal{C}_S^e} \sum_{i=1}^n |I_i|$ be the outer content of $S$.

|

||||

>

|

||||

> Let $c_i(S)=\inf_{I\in\mathcal{C}_S^i} \sum_{i=1}^n |I_i|$ be the inner content of $S$.

|

||||

>

|

||||

> _Here we use $|I|$ to denote the length of the interval $I$, in book we use volume but that's not important here._

|

||||

>

|

||||

> The content of $S$ is defined if $c(S)=c_e(S)=c_i(S)$

|

||||

|

||||

Note that from this definition, **for any pairwise disjoint collection of sets** $S_1, S_2, \cdots, S_N$, we have

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\sum_{i=1}^N c_i(S_i)\leq c_i(\bigcup_{i=1}^N S_i)\leq c_e(\bigcup_{i=1}^N S_i)\leq \sum_{i=1}^N c_e(S_i)

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

by $\sup$ and $\inf$ in the definition of $c_e(S)$ and $c_i(S)$.

|

||||

|

||||

#### Proposition 5.1

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

c_e(S)=c_i(S)+c_e(\partial S)

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

Note the boundary of $S$ is defined as $\partial S=\overline{S}\setminus S^\circ$ (corrected by Nathan Zhou).

|

||||

|

||||

> Some common notations for sets:

|

||||

>

|

||||

> $S^\circ$ is the interior of $S$. $S^\circ=\{x\in S| \exists \epsilon>0, B(x,\epsilon)\subset S\}$ (largest open set contained in $S$)

|

||||

>

|

||||

> $S'$ is the set of limit points of $S$ (derived set of $S$). $S'=\{x\in \mathbb{R}^n|\forall \epsilon>0, B(x,\epsilon)\setminus \{x\}\cap S\neq \emptyset\}$ (Topological definition of limit point).

|

||||

>

|

||||

> $\overline{S}$ is the closure of $S$. $\overline{S}=S\cup S'$ (smallest closed set containing $S$)

|

||||

|

||||

Equivalently, $\forall x\in \partial S$, $\forall \epsilon>0$, $\exists p\notin S$ and $q\notin S$ s.t. $d(x,p)<\epsilon$ and $d(x,q)<\epsilon$.

|

||||

|

||||

So the content of $S$ is defined if and only if $c_e(\partial S)=0$.

|

||||

|

||||

> Jordan Measurable

|

||||

>

|

||||

> A set $S$ is Jordan measurable if and only if $c_e(\partial S)=0$, ($c(S)=c_e(S)=c_i(S)$)

|

||||

|

||||

#### Proposition 5.2

|

||||

|

||||

Finite additivity of content:

|

||||

|

||||

Let $S_1, S_2, \cdots, S_N$ be a finite collection of pairwise disjoint Jordan measurable sets.

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

c(\bigcup_{i=1}^N S_i)=\sum_{i=1}^N c(S_i)

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

Example for Jordan measure of sets

|

||||

|

||||

| Set | Inner Content | Outer Content | Content |

|

||||

| --- | --- | --- | --- |

|

||||

| $\emptyset$ | 0 | 0 | 0 |

|

||||

| $\{q\},q\in \mathbb{R}$ | 0 | 0 | 0 |

|

||||

| $\{\frac{1}{n}\}_{n=1}^\infty$ | 0 | 0 | 0 |

|

||||

| $\{[n,n+\frac{1}{2^n}]\}_{n=1}^\infty$ | 1 | 1 | 1 |

|

||||

| $SVC(3)$ | 0 | 1 | Undefined |

|

||||

| $SVC(4)$ | 0 | $\frac{1}{2}$ | Undefined |

|

||||

| $Q\cap [0,1]$ | 0 | 1 | Undefined |

|

||||

| $[0,1]\setminus Q$ | 0 | 1 | Undefined |

|

||||

| $[a,b], a<b\in \mathbb{R}$ | $b-a$ | $b-a$ | $b-a$ |

|

||||

| $[a,b),a<b\in \mathbb{R}$ | $b-a$ | $b-a$ | $b-a$ |

|

||||

| $(a,b],a<b\in \mathbb{R}$ | $b-a$ | $b-a$ | $b-a$ |

|

||||

| $(a,b),a<b\in \mathbb{R}$ | $b-a$ | $b-a$ | $b-a$ |

|

||||

|

||||

### Borel Measure

|

||||

|

||||

Our desired property of measures:

|

||||

|

||||

1. Measure of interval is the length of the interval. $m([a,b])=m((a,b))=m([a,b))=m((a,b])=b-a$

|

||||

|

||||

2. Countable additivity: If $S_1, S_2, \cdots, S_N$ are pairwise disjoint Borel measurable sets, then $m(\bigcup_{i=1}^N S_i)=\sum_{i=1}^N m(S_i)$

|

||||

|

||||

3. Closure under set minus: If $S$ is Borel measurable and $T$ is Borel measurable, then $S\setminus T$ is Borel measurable with $m(S\setminus T)=m(S)-m(T)$

|

||||

|

||||

#### Borel Measurable Sets

|

||||

|

||||

$\mathcal{B}$ is the smallest $\sigma$-algebra that contains all closed intervals.

|

||||

|

||||

> Sigma algebra: A $\sigma$-algebra is a collection of sets that is closed under **countable** union, intersection, and complement.

|

||||

>

|

||||

> That is:

|

||||

>

|

||||

> 1. $\emptyset\in \mathcal{B}$

|

||||

> 2. If $A\in \mathcal{B}$, then $A^c\in \mathcal{B}$

|

||||

> 3. If $A_1, A_2, \cdots, A_N\in \mathcal{B}$, then $\bigcup_{i=1}^N A_i\in \mathcal{B}$

|

||||

|

||||

#### Proposition 5.3

|

||||

|

||||

Borel measurable sets does not contain all Jordan measurable sets.

|

||||

|

||||

Proof by cardinality of sets.

|

||||

|

||||

Example for Borel measure of sets

|

||||

|

||||

| Set | Borel Measure |

|

||||

| --- | --- |

|

||||

| $\emptyset$ | 0 |

|

||||

| $\{q\},q\in \mathbb{R}$ | 0 |

|

||||

| $\{\frac{1}{n}\}_{n=1}^\infty$ | 0 |

|

||||

| $\{[n,n+\frac{1}{2^n}]\}_{n=1}^\infty$ | 1 |

|

||||

| $SVC(3)$ | 0 |

|

||||

| $SVC(4)$ | 0 |

|

||||

| $Q\cap [0,1]$ | 0 |

|

||||

| $[0,1]\setminus Q$ | 1 |

|

||||

| $[a,b], a<b\in \mathbb{R}$ | $b-a$ |

|

||||

| $[a,b),a<b\in \mathbb{R}$ | $b-a$ |

|

||||

| $(a,b],a<b\in \mathbb{R}$ | $b-a$ |

|

||||

| $(a,b),a<b\in \mathbb{R}$ | $b-a$ |

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

### Lebesgue Measure

|

||||

|

||||

> Lebesgue measure

|

||||

>

|

||||

> Let $\mathcal{C}$ be the set of all countable covers of $S$.

|

||||

>

|

||||

> The Lebesgue outer measure of $S$ is defined as:

|

||||

>

|

||||

> $$m_e(S)=\inf_{C\in\mathcal{C}} \sum_{i=1}^\infty |I_i|$$

|

||||

>

|

||||

> If $S\subset[a,b]$, then the inner measure of $S$ is defined as:

|

||||

>

|

||||

> $$m_i(S)=(b-a)-m_e([a,b]\setminus S)$$

|

||||

>

|

||||

> If $m_i(S)=m_e(S)$, then $S$ is Lebesgue measurable.

|

||||

|

||||

#### Proposition 5.4

|

||||

|

||||

Subadditivity of Lebesgue outer measure:

|

||||

|

||||

For any collection of sets $S_1, S_2, \cdots, S_N$,

|

||||

|

||||

$$m_e(\bigcup_{i=1}^N S_i)\leq \sum_{i=1}^N m_e(S_i)$$

|

||||

|

||||

#### Theorem 5.5

|

||||

|

||||

If $S$ is bounded, then any of the following conditions imply that $S$ is Lebesgue measurable:

|

||||

|

||||

1. $m_e(S)=0$

|

||||

2. $S$ is countable (measure of countable set is 0)

|

||||

3. $S$ is an interval

|

||||

|

||||

> Alternative definition of Lebesgue measure

|

||||

>

|

||||

> The outer measure of $S$ is defined as the infimum of all the open sets that contain $S$.

|

||||

>

|

||||

> The inner measure of $S$ is defined as the supremum of all the closed sets that are contained in $S$.

|

||||

|

||||

#### Theorem 5.6

|

||||

|

||||

Caratheodory's criterion:

|

||||

|

||||

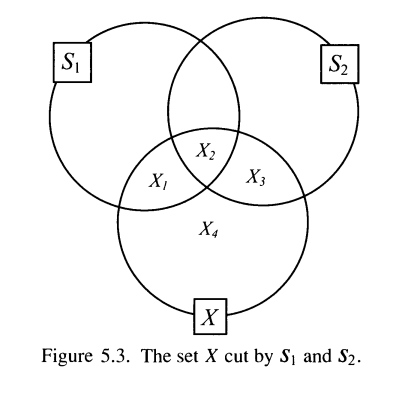

A set $S$ is Lebesgue measurable if and only if for any set $X$ with finite outer measure,

|

||||

|

||||

$$m_e(X-S)=m_e(X)-m_e(X\cap S)$$

|

||||

|

||||

#### Lemma 5.7

|

||||

|

||||

Local additivity of Lebesgue outer measure:

|

||||

|

||||

If $I_1, I_2, \cdots, I_N$ are any countable collection of **pairwise disjoint intervals** and $S$ is a bounded set, then

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

m_e\left(S\cup \bigcup_{i=1}^N I_i\right)=\sum_{i=1}^N m_e(S\cap I_i)

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

#### Theorem 5.8

|

||||

|

||||

Countable additivity of Lebesgue outer measure:

|

||||

|

||||

If $S_1, S_2, \cdots, S_N$ are any countable collection of pairwise disjoint Lebesgue measurable sets, **whose union has a finite outer measure,** then

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

m_e\left(\bigcup_{i=1}^N S_i\right)=\sum_{i=1}^N m_e(S_i)

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

#### Theorem 5.9

|

||||

|

||||

Any finite union or intersection of Lebesgue measurable sets is Lebesgue measurable.

|

||||

|

||||

#### Theorem 5.10

|

||||

|

||||

Any countable union or intersection of Lebesgue measurable sets is Lebesgue measurable.

|

||||

|

||||

#### Corollary 5.12

|

||||

|

||||

Limit of a monotone sequence of Lebesgue measurable sets is Lebesgue measurable.

|

||||

|

||||

If $S_1\subseteq S_2\subseteq S_3\subseteq \cdots$ are Lebesgue measurable sets, then $\bigcup_{i=1}^\infty S_i$ is Lebesgue measurable. And $m(\bigcup_{i=1}^\infty S_i)=\lim_{i\to\infty} m(S_i)$

|

||||

|

||||

If $S_1\supseteq S_2\supseteq S_3\supseteq \cdots$ are Lebesgue measurable sets, **and $S_1$ has finite measure**, then $\bigcap_{i=1}^\infty S_i$ is Lebesgue measurable. And $m(\bigcap_{i=1}^\infty S_i)=\lim_{i\to\infty} m(S_i)$

|

||||

|

||||

#### Theorem 5.13

|

||||

|

||||

Non-measurable sets (under axiom of choice)

|

||||

|

||||

Note that $(0,1)\subseteq \bigcup_{q\in \mathbb{Q}\cap (-1,1)}(\mathcal{N}+q)\subseteq (-1,2)$

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\bigcup_{q\in \mathbb{Q}\cap (-1,1)}(\mathcal{N}+q)

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

is not Lebesgue measurable.

|

||||

|

||||

## Chapter 6: Lebesgue Integration

|

||||

|

||||

### Lebesgue Integral

|

||||

|

||||

Let the partition on y-axis be $l=l_0<l_1<\cdots<l_n=L$, and $S_i=\{x|l_i<f(x)<l_{i+1}\}$

|

||||

|

||||

The Lebesgue integral of $f$ over $[a,b]$ is bounded by:

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\sum_{i=0}^{n-1} l_i m(S_i)\leq \int_a^b f(x) \, dx\leq \sum_{i=0}^{n-1} l_{i+1} m(S_i)

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

> Definition of measurable function:

|

||||

>

|

||||

> A function $f$ is measurable if for all $c\in \mathbb{R}$, the set $\{x\in [a,b]|f(x)>c\}$ is Lebesgue measurable.

|

||||

>

|

||||

> Equivalently, a function $f$ is measurable if any of the following conditions hold:

|

||||

>

|

||||

> 1. For all $c\in \mathbb{R}$, the set $\{x\in [a,b]|f(x)>c\}$ is Lebesgue measurable.

|

||||

> 2. For all $c\in \mathbb{R}$, the set $\{x\in [a,b]|f(x)\geq c\}$ is Lebesgue measurable.

|

||||

> 3. For all $c\in \mathbb{R}$, the set $\{x\in [a,b]|f(x)<c\}$ is Lebesgue measurable.

|

||||

> 4. For all $c\in \mathbb{R}$, the set $\{x\in [a,b]|f(x)\leq c\}$ is Lebesgue measurable.

|

||||

> 5. For all $c<d\in \mathbb{R}$, the set $\{x\in [a,b]|c\leq f(x)<d\}$ is Lebesgue measurable.

|

||||

>

|

||||

> Prove by using the fact$\{x\in [a,b]|f(x)\geq c\}=\bigcap_{n=1}^\infty \{x\in [a,b]|f(x)>c-\frac{1}{n}\}$

|

||||

|

||||

#### Proposition 6.3

|

||||

|

||||

If $f,g$ is a measurable function, and $k\in \mathbb{R}$, then $f+g,kf,f^2,fg,|f|$ is measurable.

|

||||

|

||||

> Definition of almost everywhere:

|

||||

>

|

||||

> A property holds almost everywhere if it holds everywhere except for a set of Lebesgue measure 0.

|

||||

|

||||

#### Proposition 6.4

|

||||

|

||||

If $f_n$ is a sequence of measurable functions, then $\limsup_{n\to\infty} f_n, \liminf_{n\to\infty} f_n$ is measurable.

|

||||

|

||||

#### Theorem 6.5

|

||||

|

||||

Limit of measurable functions is measurable.

|

||||

|

||||

> Definition of simple function:

|

||||

>

|

||||

> A simple function is a linear combination of indicator functions of Lebesgue measurable sets.

|

||||

|

||||

#### Theorem 6.6

|

||||

|

||||

Measurable function as limit of simple functions.

|

||||

|

||||

$f$ is a measurable function if and only if ffthere exists a sequence of simple functions $f_n$ s.t. $f_n\to f$ almost everywhere.

|

||||

|

||||

### Integration

|

||||

|

||||

#### Proposition 6.10

|

||||

|

||||

Let $\phi,\psi$ be simple functions, $c\in \mathbb{R}$ and $E=E_1\cup E_2$ where $E_1\cap E_2=\emptyset$.

|

||||

|

||||

Then

|

||||

|

||||

1. $\int_E \phi(x) \, dx=\int_{E_1} \phi(x) \, dx+\int_{E_2} \phi(x) \, dx$

|

||||

2. $\int_E (c\phi)(x) \, dx=c\int_E \phi(x) \, dx$

|

||||

3. $\int_E (\phi+\psi)(x) \, dx=\int_E \phi(x) \, dx+\int_E \psi(x) \, dx$

|

||||

4. If $\phi\leq \psi$ for all $x\in E$, then $\int_E \phi(x) \, dx\leq \int_E \psi(x) \, dx$

|

||||

|

||||

> Definition of Lebesgue integral of simple function:

|

||||

>

|

||||

> Let $\phi$ be a simple function, $\phi=\sum_{i=1}^n l_i \chi_{S_i}$

|

||||

>

|

||||

> $$\int_E \phi(x) \, dx=\sum_{i=1}^n l_i m(S_i\cap E)$$

|

||||

|

||||

> Definition of Lebesgue integral of measurable function:

|

||||

>

|

||||

> Let $f$ be a nonnegative measurable function, then

|

||||

>

|

||||

> $$\int_E f(x) \, dx=\sup_{\phi\leq f} \int_E \phi(x) \, dx$$

|

||||

>

|

||||

> If $f$ is not nonnegative, then

|

||||

>

|

||||

> $$\int_E f(x) \, dx=\int_E f^+(x) \, dx-\int_E f^-(x) \, dx$$

|

||||

>

|

||||

> where $f^+(x)=\max(f(x),0)$ and $f^-(x)=\max(-f(x),0)$

|

||||

|

||||

#### Proposition 6.12

|

||||

|

||||

Integral over a set of measure 0 is 0.

|

||||

|

||||

#### Theorem 6.13

|

||||

|

||||

If a nonnegative measurable function $f$ has integral 0 on a set $E$, then $f(x)=0$ almost everywhere on $E$.

|

||||

|

||||

#### Theorem 6.14

|

||||

|

||||

Monotone convergence theorem:

|

||||

|

||||

If $f_n$ is a sequence of monotone increasing measurable functions and $f_n\to f$ almost everywhere, and $\exists A>0$ s.t. $|\int_E f_n(x) \, dx|\leq A$ for all $n$, then $f(x)=\lim_{n\to\infty} f_n(x)$ exists almost everywhere and it's integrable on $E$ with

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\int_E f(x) \, dx=\lim_{n\to\infty} \int_E f_n(x) \, dx

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

#### Theorem 6.19

|

||||

|

||||

Dominated convergence theorem:

|

||||

|

||||

If $f_n$ is a sequence of integrable functions and $f_n\to f$ almost everywhere, and there exists a nonnegative integrable function $g$ s.t. $|f_n(x)|\leq g(x)$ for all $x\in E$ and all $n$, then $f(x)=\lim_{n\to\infty} f_n(x)$ exists almost everywhere and it's integrable on $E$ with

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\int_E f(x) \, dx=\lim_{n\to\infty} \int_E f_n(x) \, dx

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

#### Theorem 6.20

|

||||

|

||||

Fatou's lemma:

|

||||

|

||||

If $f_n$ is a sequence of nonnegative integrable functions, then

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\int_E \liminf_{n\to\infty} f_n(x) \, dx\leq \liminf_{n\to\infty} \int_E f_n(x) \, dx

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

> Definition of Hardy-Littlewood maximal function

|

||||

>

|

||||

> Given integrable $f$m and an interval $I$, look at the averaging operator $A_I f(x)=\frac{\chi_I(x)}{m(I)}\int_I f(y)dy$.

|

||||

>

|

||||

> The maximal function is defined as

|

||||

>

|

||||

> $$f^*(x)=\sup_{I \text{ is an open interval}} A_I f(x)$$

|

||||

|

||||

### Lebesgue's Fundamental theorem of calculus

|

||||

|

||||

If $f$ is Lebesgue integrable on $[a,b]$, then $F(x) = \int_a^x f(t)dt$ is differentiable **almost everywhere** and $F'(x) = f(x)$ **almost everywhere**.

|

||||

|

||||

Outline:

|

||||

|

||||

Let $\lambda,\epsilon > 0$. Find $g$ continuous such that $\int_{\mathbb{R}}|f-g|dm < \frac{\lambda \epsilon}{5}$.

|

||||

|

||||

To control $A_I f(x)-f(x)=(A_I(f-g)(x))+(A_I g(x)-g(x))+(g(x)-f(x))$, we need to estimate the three terms separately.

|

||||

|

||||

Our goal is to show that $\lim_{r\to 0^+}\sup_{I\text{ is open interval}, m(I)<r, x\in I}|A_I f(x)-f(x)|=0$. For $x$ almost every $x\in[a,b]$.

|

||||

|

||||

@@ -1,111 +0,0 @@

|

||||

# Math4121 Lecture 1

|

||||

|

||||

## Chapter 5: Differentiation

|

||||

|

||||

### The derivative of a real function

|

||||

|

||||

#### Definition 5.1

|

||||

|

||||

Let $f$ be a real-valued function on an interval $[a,b]$ ($f: [a,b] \to \mathbb{R}$).

|

||||

|

||||

We say that $f$ is _differentiable_ at a point $x\in [a,b]$ if the limit

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\lim_{t\to x} \frac{f(t)-f(x)}{t-x}

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

exists.

|

||||

|

||||

Then we defined the derivative of $f$, $f'$, a function whose domain is the set of all $x\in [a,b]$ at which $f$ is differentiable, by

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

f'(x) = \lim_{t\to x} \frac{f(t)-f(x)}{t-x}

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

#### Theorem 5.2

|

||||

|

||||

Let $f:[a,b]\to \mathbb{R}$. If $f$ is differentiable at $x\in [a,b]$, then $f$ is continuous at $x$.

|

||||

|

||||

Proof:

|

||||

|

||||

> Recall [Definition 4.5](https://notenextra.trance-0.com/Math4111/Math4111_L22#definition-45)

|

||||

>

|

||||

> $f$ is continuous at $x$ if $\forall \epsilon > 0, \exists \delta > 0$ such that if $|t-x| < \delta$, then $|f(t)-f(x)| < \epsilon$.

|

||||

>

|

||||

> Whenever you see a limit, you should think of this definition.

|

||||

|

||||

We need to show that $\lim_{t\to x} f(t) = f(x)$.

|

||||

|

||||

Equivalently, we need to show that

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\lim_{t\to x} (f(t)-f(x)) = 0

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

So for $t\ne x$, since $f$ is differentiable at $x$, we have

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\begin{aligned}

|

||||

\lim_{t\to x} (f(t)-f(x)) &= \lim_{t\to x} \left(\frac{f(t)-f(x)}{t-x}\right)(t-x) \\

|

||||

&= \lim_{t\to x} \left(\frac{f(t)-f(x)}{t-x}\right) \lim_{t\to x} (t-x) \\

|

||||

&= f'(x) \cdot 0 \\

|

||||

&= 0

|

||||

\end{aligned}

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

Therefore, differentiable is a stronger condition than continuous.

|

||||

|

||||

> There exists some function that is continuous but not differentiable.

|

||||

>

|

||||

> For example, $f(x) = |x|$ is continuous at $x=0$, but not differentiable at $x=0$.

|

||||

>

|

||||

> We can see that the left-hand limit and the right-hand limit are not the same.

|

||||

>

|

||||

> $$ \lim_{t\to 0^-} \frac{|t|-|0|}{t-0} = -1 \quad \text{and} \quad \lim_{t\to 0^+} \frac{|t|-|0|}{t-0} = 1 $$

|

||||

>

|

||||

> Therefore, the limit does not exist. for $f(x) = |x|$ at $x=0$.

|

||||

|

||||

#### Theorem 5.3

|

||||

|

||||

Suppose $f$ is differentiable at $x\in [a,b]$ and $g$ is differentiable at a point $x\in [a,b]$. Then $f+g$, $fg$ and $f/g$ are differentiable at $x$, and

|

||||

|

||||

(a) $(f+g)'(x) = f'(x) + g'(x)$

|

||||

(b) $(fg)'(x) = f'(x)g(x) + f(x)g'(x)$

|

||||

(c) $\left(\frac{f}{g}\right)'(x) = \frac{f'(x)g(x) - f(x)g'(x)}{g(x)^2}$, provided $g(x)\ne 0$

|

||||

|

||||

Proof:

|

||||

|

||||

Since the limit of product is the product of the limits, we can use the definition of the derivative to prove the theorem.

|

||||

|

||||

(a)

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\begin{aligned}

|

||||

(f+g)'(x) &= \lim_{t\to x} \frac{(f+g)(t)-(f+g)(x)}{t-x} \\

|

||||

&= \lim_{t\to x} \frac{f(t)-f(x)}{t-x} + \lim_{t\to x} \frac{g(t)-g(x)}{t-x} \\

|

||||

&= f'(x) + g'(x)

|

||||

\end{aligned}

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

(b)

|

||||

|

||||

Since $f$ is differentiable at $x$, we have $\lim_{t\to x} f(t) = f(x)$.

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\begin{aligned}

|

||||

(fg)'(x) &= \lim_{t\to x} \left(\frac{f(t)g(t)-f(x)g(x)}{t-x}\right) \\

|

||||

&= \lim_{t\to x} \left(f(t)\frac{g(t)-g(x)}{t-x} + g(x)\frac{f(t)-f(x)}{t-x}\right) \\

|

||||

&= f(t) \lim_{t\to x} \frac{g(t)-g(x)}{t-x} + g(x) \lim_{t\to x} \frac{f(t)-f(x)}{t-x} \\

|

||||

&= f(x)g'(x) + g(x)f'(x)

|

||||

\end{aligned}

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

(c)

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\begin{aligned}

|

||||

\left(\frac{f}{g}\right)'(x) &= \lim_{t\to x}\left(\frac{f(t)g(x)}{g(t)g(x)} - \frac{f(x)g(x)}{g(t)g(x)}\right) \\

|

||||

&= \frac{1}{g(t)g(x)}\left(\lim_{t\to x} (f(t)g(x)-f(x)g(t))\right) \\

|

||||

\end{aligned}

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

@@ -1,109 +0,0 @@

|

||||

# Math4121 Lecture 10

|

||||

|

||||

## Recap

|

||||

|

||||

### Properties of Riemann-Stieltjes Integral

|

||||

|

||||

#### Linearity (Theorem 6.12 (a))

|

||||

|

||||

If $f,g\in \mathscr{R}(\alpha)$ on $[a, b]\subset \mathbb{R},c,d\in \mathbb{R}$, then $cf+dg\in \mathscr{R}(\alpha)$ on $[a, b]$ and

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\int_a^b (cf+dg)d\alpha = c\int_a^b f d\alpha + d\int_a^b g d\alpha

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

#### Composition (Theorem 6.11)

|

||||

|

||||

Suppose $f\in \mathscr{R}(\alpha)$ on $[a, b]$, $m\leq f(x)\leq M$ for all $x\in [a, b]$, and $\phi$ is continuous on $[m, M]$, and let $h(x)=\phi(f(x))$ on $[a, b]$. Then $h\in \mathscr{R}(\alpha)$ on $[a, b]$.

|

||||

|

||||

#### Monotonicity (Theorem 6.12 (b))

|

||||

|

||||

If $f,g\in \mathscr{R}(\alpha)$ on $[a, b]$, and $f(x)\leq g(x),\forall x\in [a, b]$, then $\int_a^b f d\alpha \leq \int_a^b g d\alpha$.

|

||||

|

||||

## Continue on Chapter 6

|

||||

|

||||

### Properties of Integrable Functions

|

||||

|

||||

#### Theorem 6.13

|

||||

|

||||

Suppose $f,g\in \mathscr{R}(\alpha)$ on $[a, b]$, and $c\in (a, b)$. Then

|

||||

|

||||

(a) $fg\in \mathscr{R}(\alpha)$ on $[a, b]$.

|

||||

|

||||

Proof:

|

||||

|

||||

By linearity, $f+g,f-g\in \mathscr{R}(\alpha)$ on $[a, b]$.

|

||||

|

||||

Moreover, let $\phi(x)=x^2$, which is continuous on $\mathbb{R}$.

|

||||

|

||||

By **Theorem 6.11**, $f^2,g^2\in \mathscr{R}(\alpha)$ on $[a, b]$.

|

||||

|

||||

By linearity, $fg=1/4((f+g)^2-(f-g)^2)\in \mathscr{R}(\alpha)$ on $[a, b]$.

|

||||

|

||||

QED

|

||||

|

||||

(b) $|f|\in \mathscr{R}(\alpha)$ on $[a, b]$, and $|\int_a^b f d\alpha|\leq \int_a^b |f| d\alpha$.

|

||||

|

||||

Proof:

|

||||

|

||||

Let $\phi(x)=|x|$, which is continuous on $\mathbb{R}$.

|

||||

|

||||

By **Theorem 6.11**, $|f|\in \mathscr{R}(\alpha)$ on $[a, b]$.

|

||||

|

||||

Let $c=-1$ or $c=1$. such that $c\int_a^b f d\alpha=| \int_a^b f d\alpha|$.

|

||||

|

||||

By linearity, $c\int_a^b f d\alpha=\int_a^b cfd\alpha$. Since $cf\leq |f|$, by monotonicity, $|\int_a^b cfd\alpha|=\int_a^b cfd\alpha\leq \int_a^b |f| d\alpha$.

|

||||

|

||||

QED

|

||||

|

||||

### Indicator Function

|

||||

|

||||

#### Definition 6.14

|

||||

|

||||

The unit step function is defined as

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

I(x)=\begin{cases}

|

||||

0, & x\le 0 \\

|

||||

1, & x>0

|

||||

\end{cases}

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

#### Theorem 6.15

|

||||

|

||||

Let $a<s<b$. $f$ is bounded on $[a, b]$ and continuous at $s$. Define $\alpha(x)=I(x-s)$ on $[a, b]$. Then $f\in \mathscr{R}(\alpha)$ on $[a, b]$, and $\int_a^b f d\alpha=f(s)$.

|

||||

|

||||

Proof:

|

||||

|

||||

Under the hypothesis, $f$ is bounded on $[a, b]$ and continuous at $s$.

|

||||

|

||||

We can choose partition $P=\{x_0,x_1,x_2,x_3\}$ such that $a=x_0<x_1=s<x_2<x_3=b$.

|

||||

|

||||

Then,

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\begin{aligned}

|

||||

U(P,f,\alpha)&=\sum_{i=1}^3 M_i(\alpha(x_i)-\alpha(x_{i-1}))\\

|

||||

&=M_1(0-0)+M_2(1-0)+M_3(1-1)\\

|

||||

&=\sup_{x\in [s,x_2]}f(x)(\alpha(x_2)-\alpha(s))\\

|

||||

&=\sup_{x\in [s,x_2]}f(x)(1-0)\\

|

||||

&=M_2 \\

|

||||

\end{aligned}

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\begin{aligned}

|

||||

L(P,f,\alpha)&=\sum_{i=1}^3 m_i(\alpha(x_i)-\alpha(x_{i-1}))\\

|

||||

&=m_1(0-0)+m_2(1-0)+m_3(1-1)\\

|

||||

&=\inf_{x\in [s,x_2]}f(x)(\alpha(x_2)-\alpha(s))\\

|

||||

&=\inf_{x\in [s,x_2]}f(x)(1-0)\\

|

||||

&=m_2 \\

|

||||

\end{aligned}

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

Since $f$ is continuous at $s$, when $x\to s$, $U(P,f,\alpha)\to f(s)$ and $L(P,f,\alpha)\to f(s)$.

|

||||

|

||||

Therefore, $U(P,f,\alpha)-L(P,f,\alpha)\to 0$, $f\in \mathscr{R}(\alpha)$ on $[a, b]$, and $\int_a^b f d\alpha=f(s)$.

|

||||

|

||||

QED

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

@@ -1,110 +0,0 @@

|

||||

# Lecture 11

|

||||

|

||||

## Recap

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

I(x)=\begin{cases}

|

||||

0 & x\leq 0 \\

|

||||

1 & x>0

|

||||

\end{cases}

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

## Continue on Chapter 6

|

||||

|

||||

### The step function

|

||||

|

||||

#### Theorem 6.16

|

||||

|

||||

If $\sum c_n$ converges and $\{s_n\}$ is a sequence of distinct elements of $(a,b)$, and $f$ is continuous on $[a,b]$, and $\alpha(x)=\sum_{n=1}^{\infty}c_nI(x-s_n)$, then $\int_a^bf \ d\alpha=\sum_{n=1}^{\infty}c_nf(s_n)$.

|

||||

|

||||

Proof:

|

||||

|

||||

For each $x$, $I(x-s_n)\leq 1$ so $\sum_{n=1}^{\infty}c_nI(x-s_n)\leq \sum_{n=1}^{\infty}c_n$ converges (by comparison test).

|

||||

|

||||

Let $\epsilon>0$. We can find $N$ such that $\sum_{n=N+1}^{\infty}c_n<\epsilon$. (Recall that the series $\sum_{n=1}^{\infty}c_n$ converges if and only if $\lim_{N\to\infty}\sum_{n=1}^{N}c_n$ exists.)

|

||||

|

||||

Set $\alpha_1(x)=\sum_{n=1}^{N}c_nI(x-s_n)$, and $\alpha_2(x)=\sum_{n=N+1}^{\infty}c_nI(x-s_n)$.

|

||||

|

||||

Using the linearity of the integral, we have

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\int_a^b f\ d\alpha_1= \sum_{n=1}^{N}c_n\int_a^b fd(I(x-s_n))= \sum_{n=1}^{N}c_nf(s_n)

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

On the other hand, with $M=\sup|f|$,

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\left|\int_a^b f\ d\alpha_2\right|\leq \int_a^b |f|\ d\alpha_2\leq M\int_a^b \alpha_2\ dx=M\sum_{n=N+1}^{\infty}c_n(b-s_n)<\epsilon

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

So,

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\begin{aligned}

|

||||

\left|\int_a^b f\ d\alpha-\sum_{n=1}^{\infty}c_nf(s_n)\right|&= \left|\int_a^b f\ d\alpha_2-\sum_{n=N+1}^{\infty}c_nf(s_n)\right|\\

|

||||

&\leq |M\epsilon-\sum_{n=N+1}^{\infty}|c_n|M(b-s_n)|\\

|

||||

&<2M\epsilon

|

||||

\end{aligned}

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

Since $\epsilon$ is arbitrary, we have $\int_a^b f\ d\alpha=\sum_{n=1}^{\infty}c_nf(s_n)$.

|

||||

|

||||

### Integration and differentiation

|

||||

|

||||

#### Theorem 6.20 Fundamental theorem of calculus

|

||||

|

||||

Let $f\in \mathscr{R}$ for $x\in [a,b]$. We define $F(x)=\int_a^x f(t)\ dt$. Then $F$ is continuous and if $f$ is continuous at $x_0\in [a,b]$, then $F$ is differentiable at $x_0$ and $F'(x_0)=f(x_0)$.

|

||||

|

||||

Proof:

|

||||

|

||||

Let $x<y,x,y\in [a,b]$. Then,

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|F(y)-F(x)|=\left|\int_a^y f(t)\ dt-\int_a^x f(t)\ dt\right|=\left|\int_x^y f(t)\ dt\right|\leq \sup|f|\cdot (y-x)

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

So, $F$ is continuous on $[a,b]$.

|

||||

|

||||

Now, let $f$ be continuous at $x_0\in (a,b)$ and $\epsilon>0$. Then we can find $\delta>0$ such that $a<x_0-\delta<s<x_0<t<x_0+\delta<b$ and $|f(u)-f(x_0)|<\epsilon$ for all $u\in (x_0-\delta,x_0+\delta)$.

|

||||

|

||||

So,

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\begin{aligned}

|

||||

\left|\frac{F(s)-F(x_0)}{s-x_0}-f(x_0)\right|&=\left|\frac{1}{s-x_0}\left(\int_a^s f(u)\ du-\int_a^{x_0} f(u)\ du\right)-f(x_0)\right|\\

|

||||

&=\left|\frac{1}{s-x_0}\left(\int_s^{x_0} f(u)\ du\right)-\frac{1}{s-x_0}\left(\int_s^{x_0} f(x_0)\ dv\right)-f(x_0)\right|\\

|

||||

&=\left|\frac{1}{x_0-s}\left(\int_s^{x_0} [f(u)-f(x_0)]\ du\right)\right|\\

|

||||

&\leq \frac{1}{x_0-s}\epsilon(x_0-s)\\

|

||||

&= \epsilon

|

||||

\end{aligned}

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

QED

|

||||

|

||||

If $f\in \mathscr{R}$, and there exists a differentiable function $F:[a,b]\to \mathbb{R}$ such that $F'=f$ on $(a,b)$, then

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\int_a^b f(x)\ dx=F(b)-F(a)

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

Proof:

|

||||

|

||||

Let $\epsilon>0$ and $P=\{x_0,x_1,\cdots,x_n\}$ be a partition of $[a,b]$.

|

||||

|

||||

By the mean value theorem, on each subinterval $[x_{i-1},x_i]$, there exists $t_i\in (x_{i-1},x_i)$ such that

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

F(x_i)-F(x_{i-1})=F'(t_i)(x_i-x_{i-1})=f(t_i)\Delta x_i

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

Since $m_i\leq f(t_i)\leq M_i$, notices that $\sum_{i=1}^n f(t_i)\Delta x_i=F(b)-F(a)$.

|

||||

|

||||

So,

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

L(P,f)\leq F(b)-F(a)\leq U(P,f)

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

So, $f\in \mathscr{R}$ and $\int_a^b f(x)\ dx=F(b)-F(a)$.

|

||||

|

||||

QED

|

||||

@@ -1,139 +0,0 @@

|

||||

# Math4121 Lecture 12

|

||||

|

||||

## Chapter 7: Uniform Convergence and Integrals

|

||||

|

||||

Our goal is to solve problems like this:

|

||||

|

||||

Let

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

s_{n,m}=\frac{m}{m+n}

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

The different order of computation gives different results:

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\lim_{n\to\infty}\lim_{m\to\infty}s_{n,m}=1

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\lim_{m\to\infty}\lim_{n\to\infty}s_{n,m}=0

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

We cannot always switch the order of limits. We cannot also do this on derivatives.

|

||||

|

||||

### Examples

|

||||

|

||||

#### Example 7.4

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

f_m(x)=\lim_{n\to\infty}cos(m!x\pi)^{2n}

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

If $cos(m!x\pi)^{2n}=\pm 1$, then $f_m(x)=1$.

|

||||

|

||||

If not, then $|cos(m!x\pi)^{2n}|<1$.

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

f_m(x)=\begin{cases}

|

||||

1 & \text{if } m!x\text{ is an integer} \\

|

||||

0 & \text{if } \text{otherwise}

|

||||

\end{cases}

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

This function "raise" the fractions with all denominators less than $m$.

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\lim_{m\to\infty}f_m(x)=

|

||||

\begin{cases}

|

||||

1 & \text{if } x\text{ is an rational number} \\

|

||||

0 & \text{if } \text{otherwise}

|

||||

\end{cases}

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

So this function is not Riemann integrable. (show in homework)

|

||||

|

||||

But

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

g_{n,m}(x)=cos(m!x\pi)^{2n}

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

is continuous, and

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\lim_{m\to\infty}\lim_{n\to\infty}g_{n,m}(x)=f(x)

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

So the function is not Riemann integrable.

|

||||

|

||||

#### Definition 7.7

|

||||

|

||||

A sequence of functions $\{f_n\}$ **converges uniformly** to $f$ on set $E$ if

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\forall \epsilon>0, \exists N, \forall n\geq N, \forall x\in E, |f_n(x)-f(x)|<\epsilon

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

If $E$ is just a point, then it is the common definition of convergence.

|

||||

|

||||

_If you have uniform convergence, then you can switch the order of limits._

|

||||

|

||||

### Uniform Convergence and Integrals

|

||||

|

||||

#### Theorem 7.16

|

||||

|

||||

Suppose $\{f_n\}\in\mathscr{R}(\alpha)$ on $[a,b]$ that converges uniformly to $f$ on $[a,b]$. Then $f\in\mathscr{R}(\alpha)$ on $[a,b]$ and

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\int_a^b f(x)d\alpha=\lim_{n\to\infty}\int_a^b f_n(x)d\alpha

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

#### Proof

|

||||

|

||||

Define $\epsilon_n=\sup_{x\in[a,b]}|f_n(x)-f(x)|$.

|

||||

|

||||

By uniform convergence, $\epsilon_n\to 0$ as $n\to\infty$.

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

f_n(x)-\epsilon_n\leq f(x)\leq f_n(x)+\epsilon_n

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\int_a^b f_n-\epsilon_nd\alpha\leq\overline{\int_a^b}fd\alpha\leq\int_a^bf_n+\epsilon_nd\alpha

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\int_a^b f_n-\epsilon_n d\alpha\leq\underline{\int_a^b}fd\alpha\leq\int_a^b f_n+\epsilon_n d\alpha

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

So,

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

0\leq\overline{\int_a^b}fd\alpha-\underline{\int_a^b}fd\alpha\leq\int_a^b \epsilon_n d\alpha+\int_a^b \epsilon_n d\alpha=2\epsilon_n[\alpha(b)-\alpha(a)]

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

So $f\in\mathscr{R}(\alpha)$ and

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\int_a^b fd\alpha\leq \int_a^b f_n d\alpha+\int_a^b \epsilon_n d\alpha\leq \int_a^b fd\alpha+2\epsilon_n d\alpha

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

So,

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\int_a^b fd\alpha-\int_a^b \epsilon_n d\alpha\leq \int_a^b f_n d\alpha\leq \int_a^b fd\alpha+\int_a^b \epsilon_n d\alpha

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

Since $\int_a^b \epsilon_n d\alpha\to 0$ as $n\to\infty$, by the squeeze theorem, we have

|

||||

|

||||

by the squeeze theorem, we have

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\lim_{n\to\infty}\int_a^b f_nd\alpha=\int_a^b fd\alpha

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

_Key is that $\int_a^b (f-f_n)d\alpha\leq \sup_{x\in[a,b]}|f-f_n|(\alpha(b)-\alpha(a))$_

|

||||

|

||||

@@ -1,171 +0,0 @@

|

||||

# Math4121 Lecture 13

|

||||

|

||||

## Hidden Chapter 1

|

||||

|

||||

This chapter is not covered in the lecture but I still want to mention it here.

|

||||

|

||||

At first, when the integral was first invented, it was thought to be the area under the curve or above the curve, using intuitive geometric definition from the mysterious common sense of the homo-sapiens. There was not a rigorous definition of the integral from the eighteenth century, when it was first invented, to the nineteenth century, when Riemann, Lebesgue, and others rigorously defined the integral.

|

||||

|

||||

The integral was thought to be the anti-derivative, for the general publics.

|

||||

|

||||

However, we want to apply the integral to more general functions, rather than just the differentiable functions.

|

||||

|

||||

So, we need a rigorous definition of the integral, one potential solution is the Cauchy-Riemann integral.

|

||||

|

||||

### Riemann integral

|

||||

|

||||

Recall from the previous lectures, we have the following definition of the Riemann integral:

|

||||

|

||||

A function $f$ is Riemann integrable on $[a,b]$ if there exists a number $V$ such that for every $\epsilon>0$, there exists a $\delta>0$ such that for every partition $P=\{x_0=a,x_1,\cdots,x_n=b\}$ of $[a,b]$ with mesh less than $\delta$, we have

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\left|\sum_{i=1}^{n}f(x_i^*)(x_i-x_{i-1})-V\right|<\epsilon

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

where $x_i^*$ is a point in the $i$-th subinterval $[x_{i-1},x_i]$.

|

||||

|

||||

This sum only exists if the Darboux's sum defined by the following is small:

|

||||

|

||||

### Darboux's sum

|

||||

|

||||

Let $M_i=\sup_{x\in [x_{i-1},x_i]}f(x)$ and $m_i=\inf_{x\in [x_{i-1},x_i]}f(x)$.

|

||||

|

||||

Then, the Darboux's sum is defined as

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\underline{S}(f,P)=\sum_{i=1}^{n}m_i(x_i-x_{i-1})

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

and

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\overline{S}(f,P)=\sum_{i=1}^{n}M_i(x_i-x_{i-1})

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

In this case, small means that $\forall \epsilon>0$, there exists a $\delta>0$ such that if $x_i-x_{i-1}<\delta$, then

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\sum_{i=1}^{n}(M_i-m_i)(x_i-x_{i-1})<\epsilon

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

$(M_i-m_i)$ is the oscillation of $f$ on the $i$-th subinterval $[x_{i-1},x_i]$.

|

||||

|

||||

#### Theorem 2.1: Riemann's Integrability Criterion (corollary version)

|

||||

|

||||