Compare commits

20 Commits

bce2fa426c

...

main

| Author | SHA1 | Date | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

0e28ba6261 | ||

|

|

c4888b796c | ||

|

|

a7ef223f67 | ||

|

|

005cd7dbd6 | ||

|

|

ef9059d27c | ||

|

|

bdf0ff9f06 | ||

|

|

669e1c889a | ||

|

|

b6b80f619a | ||

|

|

2529a251e7 | ||

|

|

5b103812b4 | ||

|

|

16f09e5723 | ||

|

|

83ada2df2a | ||

|

|

8f2e613b36 | ||

|

|

e69362ce3c | ||

|

|

6a0b35bb28 | ||

|

|

778538cce0 | ||

|

|

f3c54c4dc7 | ||

|

|

a861477d74 | ||

|

|

c51226328c | ||

|

|

ba9aedfc5a |

5

content/CSE4303/CSE4303_L6.md

Normal file

5

content/CSE4303/CSE4303_L6.md

Normal file

@@ -0,0 +1,5 @@

|

||||

# CSE4303 Introduction to Computer Security (Lecture 6)

|

||||

|

||||

Refer to this lecture notes

|

||||

|

||||

[CSE442T Lecture 3](https://notenextra.trance-0.com/CSE442T/CSE442T_L3/)

|

||||

144

content/CSE4303/CSE4303_L7.md

Normal file

144

content/CSE4303/CSE4303_L7.md

Normal file

@@ -0,0 +1,144 @@

|

||||

# CSE4303 Introduction to Computer Security (Lecture 7)

|

||||

|

||||

## Cryptography in Symmetric Systems

|

||||

|

||||

### Symmetric systems

|

||||

|

||||

Symmetric (shared-key) encryption

|

||||

|

||||

- Classical techniques

|

||||

- Computer-aided techniques

|

||||

- Formal reasoning

|

||||

- Realizations:

|

||||

- Stream ciphers

|

||||

- Block ciphers

|

||||

|

||||

## Stream ciphers

|

||||

|

||||

1. Operate on PT one bit at a time (usually), as a bit "stream"

|

||||

2. Generate arbitrarily long keystream on demand

|

||||

|

||||

### Keystream

|

||||

|

||||

Keystream $G(k)$ generated from key $k$.

|

||||

|

||||

Encryption:

|

||||

$$

|

||||

E(k,m) = m \oplus G(k)

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

Decryption:

|

||||

$$

|

||||

D(k,c) = c \oplus G(k)

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

### Security abstraction

|

||||

|

||||

1. XOR transfers randomness of keystream to randomness of CT regardless of PT’s content

|

||||

2. Security depends on $G$ being "practically" indistinguishable from random string and "practically" unpredictable

|

||||

3. Idea: shouldn’t be able to predict next bit of generator given all bits seen so far

|

||||

|

||||

### Keystream $G(k)$

|

||||

|

||||

- Idea: shouldn’t be able to predict next bit of generator given all bits seen so far

|

||||

- Strategies and challenges: many!

|

||||

|

||||

#### Idea that doesn’t quite work: Linear Feedback Shift Register (LFSR)

|

||||

|

||||

- Choice of feedback: by algebra

|

||||

- Pro: fast, statistically close to random

|

||||

- Problem: susceptible to cryptanalysis (because linear)

|

||||

|

||||

#### LFSR-based modifications

|

||||

|

||||

- Use non-linear combo of multiple LFSRs

|

||||

- Use controlled clocking (e.g. only cycle the LFSR when another LFSR outputs a 1)

|

||||

- Etc.

|

||||

|

||||

#### Others

|

||||

|

||||

- Modular arithmetic-based constructions

|

||||

- Other algebraic constructions

|

||||

|

||||

### Hazards

|

||||

|

||||

1. Weak PRG

|

||||

2. Key re-use

|

||||

3. Predictable effect of modifying CT on decrypted PT

|

||||

|

||||

#### Weak PRG

|

||||

|

||||

- Makes semantic security impossible

|

||||

|

||||

#### Key re-use

|

||||

|

||||

Suppose:

|

||||

$$

|

||||

c_1 = m_1 \oplus G(k)

|

||||

$$

|

||||

and

|

||||

$$

|

||||

c_2 = m_2 \oplus G(k)

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

Then:

|

||||

$$

|

||||

c_1 \oplus c_2 = m_1 \oplus m_2

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

This may be enough to recover $m_1$ or $m_2$ using natural language properties.

|

||||

|

||||

##### IV (Initialization Vector)

|

||||

|

||||

Used to avoid key re-use:

|

||||

|

||||

- IV incremented per frame

|

||||

- But repeats after $2^{24}$ frames

|

||||

- Sometimes resets to 0

|

||||

- Enough to recover key within minutes

|

||||

|

||||

Note:

|

||||

|

||||

- Happens if keystream period is too short

|

||||

- Real-world example: WEP attack (802.11b)

|

||||

|

||||

#### Predictable modification of ciphertext

|

||||

|

||||

If attacker modifies ciphertext by XORing $p$:

|

||||

|

||||

Ciphertext becomes:

|

||||

$$

|

||||

(m \oplus k) \oplus p

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

Decryption yields:

|

||||

$$

|

||||

m \oplus p

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

- Affects integrity

|

||||

- Not CCA-secure for integrity

|

||||

|

||||

### Summary: Stream ciphers

|

||||

|

||||

Pros

|

||||

|

||||

- Fast

|

||||

- Memory-efficient

|

||||

- No minimum PT size

|

||||

|

||||

Cons

|

||||

|

||||

- Require good PRG

|

||||

- Can never re-use key

|

||||

- No integrity mechanism

|

||||

|

||||

Note

|

||||

|

||||

- Integrity mechanisms exist for other symmetric ciphers (block ciphers)

|

||||

- "Authenticated encryption"

|

||||

|

||||

Examples / Uses

|

||||

|

||||

- RC4: legacy stream cipher (e.g. WEP)

|

||||

- ChaCha / Salsa: Android cell phone encryption (Adiantum)

|

||||

320

content/CSE4303/CSE4303_L8.md

Normal file

320

content/CSE4303/CSE4303_L8.md

Normal file

@@ -0,0 +1,320 @@

|

||||

# CSE4303 Introduction to Computer Security (Lecture 8)

|

||||

|

||||

## Block ciphers

|

||||

|

||||

1. Operate on PT one block at a time

|

||||

2. Use same key for multiple blocks (with caveats)

|

||||

3. Chaining modes intertwine successive blocks of CT (or not)

|

||||

|

||||

## Security abstraction

|

||||

|

||||

View cipher as a Pseudo-Random Permutation (PRP)

|

||||

|

||||

### Background: Pseudo-Random Function (PRF)

|

||||

|

||||

Defined over $(K,X,Y)$:

|

||||

$$

|

||||

F : K \times X \to Y

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

Such that there exists an efficient algorithm to evaluate $F(k,x)$.

|

||||

|

||||

Let:

|

||||

|

||||

- $\text{Funs}[X,Y]$ = set of all functions from $X$ to $Y$

|

||||

- $S_F = \{ F(k,\cdot) \mid k \in K \}$

|

||||

|

||||

Intuition:

|

||||

|

||||

A PRF is secure if a random function in $\text{Funs}[X,Y]$ is indistinguishable from a random function in $S_F$.

|

||||

|

||||

Adversarial game:

|

||||

|

||||

- Challenger samples $k \leftarrow K$

|

||||

- Or samples $f \leftarrow \text{Funs}[X,Y]$

|

||||

- Adversary queries oracle with $x \in X$

|

||||

- Receives either $F(k,x)$ or $f(x)$

|

||||

- Must distinguish

|

||||

|

||||

Goal: adversary’s advantage negligible

|

||||

|

||||

## PRP Definition

|

||||

|

||||

Defined over $(K,X)$:

|

||||

$$

|

||||

E : K \times X \to X

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

Such that:

|

||||

|

||||

1. Efficient deterministic algorithm to evaluate $E(k,x)$

|

||||

2. $E(k,\cdot)$ is one-to-one

|

||||

3. Efficient inversion algorithm $D(k,y)$ exists

|

||||

|

||||

i.e., a PRF that is an invertible one-to-one mapping from message space to message space

|

||||

|

||||

## Secure PRP

|

||||

|

||||

Let $\text{Perms}[X]$ be all permutations on $X$.

|

||||

|

||||

Intuition:

|

||||

|

||||

A PRP is secure if a random permutation in $\text{Perms}[X]$ is indistinguishable from a random element of:

|

||||

$$

|

||||

S_E = \{ E(k,\cdot) \mid k \in K \}

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

Adversarial game:

|

||||

|

||||

- Challenger samples $k \leftarrow K$

|

||||

- Or $\pi \leftarrow \text{Perms}[X]$

|

||||

- Adversary queries $x \in X$

|

||||

- Receives either $E(k,x)$ or $\pi(x)$

|

||||

- Must distinguish

|

||||

|

||||

Goal: negligible advantage

|

||||

|

||||

## Block cipher constructions

|

||||

|

||||

### Feistel network

|

||||

|

||||

Given:

|

||||

$$

|

||||

f_1, \dots, f_d : \{0,1\}^n \to \{0,1\}^n

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

Build invertible function:

|

||||

$$

|

||||

F : \{0,1\}^{2n} \to \{0,1\}^{2n}

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

Let input be split into $(L_0, R_0)$.

|

||||

|

||||

Round $i$:

|

||||

$$

|

||||

L_i = R_{i-1}

|

||||

$$

|

||||

$$

|

||||

R_i = L_{i-1} \oplus f_i(R_{i-1})

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

#### Invertibility

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

R_{i-1} = L_i

|

||||

$$

|

||||

$$

|

||||

L_{i-1} = R_i \oplus f_i(L_i)

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

Thus Feistel is invertible regardless of whether $f_i$ is invertible.

|

||||

|

||||

### Luby–Rackoff Theorem (1985)

|

||||

|

||||

If $f$ is a secure PRF, then 3-round Feistel is a secure PRP.

|

||||

|

||||

### DES (Data Encryption Standard) — 1976

|

||||

|

||||

- 16-round Feistel network

|

||||

- 64-bit block size

|

||||

- 56-bit key

|

||||

- Round functions:

|

||||

$$

|

||||

f_i(x) = F(k_i, x)

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

Round function uses:

|

||||

|

||||

- S-box (substitution box) — non-linear

|

||||

- P-box (permutation box)

|

||||

|

||||

To invert: use keys in reverse order.

|

||||

|

||||

Problem: 56-bit keyspace too small today (brute-force feasible).

|

||||

|

||||

### Substitution–Permutation Network (SPN)

|

||||

|

||||

Rounds of:

|

||||

|

||||

- Substitution (S-box layer)

|

||||

- Permutation (P-layer)

|

||||

- XOR with round key

|

||||

|

||||

All layers invertible.

|

||||

|

||||

### AES (Advanced Encryption Standard) — 2000

|

||||

|

||||

- 10 substitution-permutation rounds (128-bit key version)

|

||||

- 128-bit block size

|

||||

|

||||

Each round includes:

|

||||

|

||||

- ByteSub (1-byte S-box)

|

||||

- ShiftRows

|

||||

- MixColumns

|

||||

- AddRoundKey

|

||||

|

||||

Key sizes:

|

||||

|

||||

- 128-bit

|

||||

- 192-bit

|

||||

- 256-bit

|

||||

|

||||

Currently de facto standard symmetric-key cipher (e.g. TLS/SSL).

|

||||

|

||||

## Block cipher modes

|

||||

|

||||

### Challenge

|

||||

|

||||

Encrypt PTs longer than one block using same key while maintaining security.

|

||||

|

||||

### ECB (Electronic Codebook)

|

||||

|

||||

Encrypt blocks independently:

|

||||

$$

|

||||

c_i = E(k, m_i)

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

Problem:

|

||||

|

||||

If $m_1 = m_2$, then:

|

||||

$$

|

||||

c_1 = c_2

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

Not semantically secure.

|

||||

|

||||

#### Formal non-security argument

|

||||

|

||||

Two-block challenge:

|

||||

|

||||

- Adversary submits:

|

||||

- $m_0 = \text{"Hello World"}$

|

||||

- $m_1 = \text{"Hello Hello"}$

|

||||

- If $c_1 = c_2$, output 0; else 1

|

||||

|

||||

Advantage = 1

|

||||

|

||||

### CPA model (Chosen Plaintext Attack)

|

||||

|

||||

Attacker:

|

||||

|

||||

- Sees many PT/CT pairs under same key

|

||||

- Can submit arbitrary PTs

|

||||

|

||||

Definition:

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\text{Adv}_{CPA}[A,E] =

|

||||

\left|

|

||||

\Pr[\text{EXP}(0)=1] - \Pr[\text{EXP}(1)=1]

|

||||

\right|

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

Must be negligible.

|

||||

|

||||

ECB fails CPA security.

|

||||

|

||||

### Moral

|

||||

|

||||

If same secret key is used multiple times, given same PT twice, encryption must produce different CT outputs.

|

||||

|

||||

## Secure block modes

|

||||

|

||||

### Idea

|

||||

|

||||

Augment key with:

|

||||

|

||||

- Per-block nonce

|

||||

- Or chaining data from prior blocks

|

||||

|

||||

### CBC (Cipher Block Chaining)

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

c_1 = E(k, m_1 \oplus IV)

|

||||

$$

|

||||

$$

|

||||

c_i = E(k, m_i \oplus c_{i-1})

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

IV must be random/unpredictable.

|

||||

|

||||

### CFB (Cipher Feedback)

|

||||

|

||||

Uses previous ciphertext as input feedback into block cipher.

|

||||

|

||||

### OFB (Output Feedback)

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

s_i = E(k, s_{i-1})

|

||||

$$

|

||||

$$

|

||||

c_i = m_i \oplus s_i

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

Can pre-compute keystream.

|

||||

|

||||

Acts like stream cipher.

|

||||

|

||||

### CTR (Counter Mode)

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

c_i = m_i \oplus E(k, \text{nonce} \| \text{counter}_i)

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

Encryption and decryption parallelizable.

|

||||

|

||||

Nonce must be unique.

|

||||

|

||||

### GCM (Galois Counter Mode)

|

||||

|

||||

- Most popular ("AES-GCM")

|

||||

- Provides authenticated encryption

|

||||

- Confidentiality + integrity

|

||||

|

||||

## Nonce-based semantic security

|

||||

|

||||

Encryption:

|

||||

$$

|

||||

c = E(k, m, n)

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

Adversarial experiment:

|

||||

|

||||

- Challenger picks $k$

|

||||

- Adversary submits $(m_{i,0}, m_{i,1})$ and nonce $n_i$

|

||||

- Receives $c_i = E(k, m_{i,b}, n_i)$

|

||||

- Nonces must be distinct

|

||||

|

||||

Definition:

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\text{Adv}_{nCPA}[A,E] =

|

||||

\left|

|

||||

\Pr[\text{EXP}(0)=1] - \Pr[\text{EXP}(1)=1]

|

||||

\right|

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

In practice:

|

||||

|

||||

- CBC: IV must be random

|

||||

- CTR/GCM: nonce must be unique but not necessarily random

|

||||

|

||||

## Symmetric Encryption Summary

|

||||

|

||||

### Stream Ciphers

|

||||

|

||||

- Rely on secure PRG

|

||||

- No key re-use

|

||||

- Fast

|

||||

- Low memory

|

||||

- Less robust

|

||||

- No built-in integrity

|

||||

|

||||

### Block Ciphers

|

||||

|

||||

- Rely on secure PRP

|

||||

- Allow key re-use across blocks (secure mode required)

|

||||

- Provide authenticated encryption in some modes (e.g. GCM)

|

||||

- Slower

|

||||

- Higher memory

|

||||

- More robust

|

||||

- Used in most practical secure systems (e.g. TLS)

|

||||

1

content/CSE4303/CSE4303_L9.md

Normal file

1

content/CSE4303/CSE4303_L9.md

Normal file

@@ -0,0 +1 @@

|

||||

# CSE4303 Introduction to Computer Security (Lecture 9)

|

||||

@@ -8,4 +8,8 @@ export default {

|

||||

CSE4303_L3: "Introduction to Computer Security (Lecture 3)",

|

||||

CSE4303_L4: "Introduction to Computer Security (Lecture 4)",

|

||||

CSE4303_L5: "Introduction to Computer Security (Lecture 5)",

|

||||

CSE4303_L6: "Introduction to Computer Security (Lecture 6)",

|

||||

CSE4303_L7: "Introduction to Computer Security (Lecture 7)",

|

||||

CSE4303_L8: "Introduction to Computer Security (Lecture 8)",

|

||||

CSE4303_L9: "Introduction to Computer Security (Lecture 9)",

|

||||

}

|

||||

|

||||

@@ -32,241 +32,8 @@ Please refer to the syllabus for our policy regarding the use of GenAI.

|

||||

>

|

||||

> This notation system is annoying since in mathematics, $A^*$ is the transpose of $A$, but since we are using literatures in physics, we keep the notation of $A^*$. In this report, I will try to make the notation consistent as possible and follows the **physics** convention in this report. So every vector you see will be in $\ket{\psi}$ form. And we will avoid using the $\langle v,w\rangle$ notation for inner product as it used in math, we will use $\langle v|w\rangle$ or $\langle v,w\rangle$ to denote the inner product.

|

||||

|

||||

A quantum error-correcting code is defined to be a unitary mapping (encoding) of $k$ qubits (two-state quantum systems) into a subspace of the quantum state space of $n$ qubuits such that if any $t$ of the qubits undergo arbitary decoherence, not necessarily independently, the resulting $n$ qubit state can be used to faithfully reconstruct the original quantum state of the $k$ encoded qubits.

|

||||

|

||||

Asymptotic rate $k/n=1-2H_2(2t/n)$, where $H_2$ is the binary entropy function

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

H_2=-p\log_2(p)-(1-p)\log_2(1-p)

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

### Problem setting and motivation

|

||||

|

||||

#### Linear algebra 102

|

||||

|

||||

The main vector space we are interested in is $\mathbb{C}^n$, therefore, all the linear operator we defined are from $\mathbb{C}^n$ to $\mathbb{C}^n$.

|

||||

|

||||

We denote a vector in vector space as $\ket{\psi}=(z_1,\cdots,z_n)$ (might also be infinite dimensional, and $z_i\in\mathbb{C}$).

|

||||

|

||||

A natural inner product space defined on $\mathbb{C}^n$ is given by the Hermitian inner product:

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\langle\psi|\varphi\rangle=\sum_{i=1}^n z_i\bar{z}_i

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

This satisfies the following properties:

|

||||

1. $\bra{\psi}\sum_i \lambda_i\ket{\varphi}=\sum_i \lambda_i \langle\psi|\varphi\rangle$ (linear on the second argument)

|

||||

2. $\langle\varphi|\psi\rangle=(\langle\psi|\varphi\rangle)^*$

|

||||

3. $\langle\psi|\psi\rangle\geq 0$ with equality if and only if $\ket{\psi}=0$

|

||||

|

||||

Here $\psi$ is just a label for the vector and you don't need to worry about it too much. This is also called the ket, where the counterpart:

|

||||

|

||||

- $\langle\psi\rangle$ is called the bra, used to denote the vector dual to $\psi$, such element is a linear functional if you really wants to know what that is.

|

||||

- $\langle\psi|\varphi\rangle$ is the inner product between two vectors, and $\bra{\psi} A\ket{\varphi}$ is the inner product between $A\ket{\varphi}$ and $\bra{\psi}$, or equivalently $A^\dagger \bra{\psi}$ and $\ket{\varphi}$.

|

||||

- Given a complex matrix $A=\mathbb{C}^{n\times n}$,

|

||||

- $A^*$ is the complex conjugate of $A$.

|

||||

- i.e., $A=\begin{bmatrix}1+i & 2+i & 3+i\\4+i & 5+i & 6+i\\7+i & 8+i & 9+i\end{bmatrix}$, $A^*=\begin{bmatrix}1-i & 2-i & 3-i\\4-i & 5-i & 6-i\\7-i & 8-i & 9-i\end{bmatrix}$

|

||||

- $A^\top$ is the transpose of $A$.

|

||||

- i.e., $A=\begin{bmatrix}1+i & 2+i & 3+i\\4+i & 5+i & 6+i\\7+i & 8+i & 9+i\end{bmatrix}$, $A^\top=\begin{bmatrix}1+i & 4+i & 7+i\\2+i & 5+i & 8+i\\3+i & 6+i & 9+i\end{bmatrix}$

|

||||

- $A^\dagger=(A^*)^\top$ is the complex conjugate transpose, referred to as the adjoint, or Hermitian conjugate of $A$.

|

||||

- i.e., $A=\begin{bmatrix}1+i & 2+i & 3+i\\4+i & 5+i & 6+i\\7+i & 8+i & 9+i\end{bmatrix}$, $A^\dagger=\begin{bmatrix}1-i & 4-i & 7-i\\2-i & 5-i & 8-i\\3-i & 6-i & 9-i\end{bmatrix}$

|

||||

- $A$ is unitary if $A^\dagger A=AA^\dagger=I$.

|

||||

- $A$ is hermitian (self-adjoint in mathematics literatures) if $A^\dagger=A$.

|

||||

|

||||

#### Motivation of Tensor product

|

||||

|

||||

Recall from the traditional notation of product space of two vector spaces $V$ and $W$, that is, $V\times W$, is the set of all ordered pairs $(\ket{v},\ket{w})$ where $\ket{v}\in V$ and $\ket{w}\in W$.

|

||||

|

||||

The space has dimension $\dim V+\dim W$.

|

||||

|

||||

We want to define a vector space with notation of multiplication of two vectors from different vector spaces.

|

||||

|

||||

That is

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

(\ket{v_1}+\ket{v_2})\otimes \ket{w}=(\ket{v_1}\otimes \ket{w})+(\ket{v_2}\otimes \ket{w})

|

||||

$$

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\ket{v}\otimes (\ket{w_1}+\ket{w_2})=(\ket{v}\otimes \ket{w_1})+(\ket{v}\otimes \ket{w_2})

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

and enables scalar multiplication by

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\lambda (\ket{v}\otimes \ket{w})=(\lambda \ket{v})\otimes \ket{w}=\ket{v}\otimes (\lambda \ket{w})

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

And we wish to build a way associates the basis of $V$ and $W$ to the basis of $V\otimes W$. That makes the tensor product a vector space with dimension $\dim V\times \dim W$.

|

||||

|

||||

#### Definition of linear functional

|

||||

|

||||

> [!TIP]

|

||||

>

|

||||

> Note the difference between a linear functional and a linear map.

|

||||

>

|

||||

> A generalized linear map is a function $f:V\to W$ satisfying the condition

|

||||

>

|

||||

> 1. $f(\ket{u}+\ket{v})=f(\ket{u})+f(\ket{v})$

|

||||

> 2. $f(\lambda \ket{v})=\lambda f(\ket{v})$

|

||||

|

||||

A linear functional is a linear map from $V$ to $\mathbb{F}$.

|

||||

|

||||

#### Definition of bilinear functional

|

||||

|

||||

A bilinear functional is a bilinear function $\beta:V\times W\to \mathbb{F}$ satisfying the condition that $\ket{v}\to \beta(\ket{v},\ket{w})$ is a linear functional for all $\ket{w}\in W$ and $\ket{w}\to \beta(\ket{v},\ket{w})$ is a linear functional for all $\ket{v}\in V$.

|

||||

|

||||

The vector space of all bilinear functionals is denoted by $\mathcal{B}(V,W)$.

|

||||

|

||||

#### Definition of tensor product

|

||||

|

||||

Let $V,W$ be two vector spaces.

|

||||

|

||||

Let $V'$ and $W'$ be the dual spaces of $V$ and $W$, respectively, that is $V'=\{\psi:V\to \mathbb{F}\}$ and $W'=\{\phi:W\to \mathbb{F}\}$, $\psi, \phi$ are linear functionals.

|

||||

|

||||

The tensor product of vectors $v\in V$ and $w\in W$ is the bilinear functional defined by $\forall (\psi,\phi)\in V'\times W'$ given by the notation

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

(v\otimes w)(\psi,\phi)\coloneqq\psi(v)\phi(w)

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

The tensor product of two vector spaces $V$ and $W$ is the vector space $\mathcal{B}(V',W')$

|

||||

|

||||

Notice that the basis of such vector space is the linear combination of the basis of $V'$ and $W'$, that is, if $\{e_i\}$ is the basis of $V'$ and $\{f_j\}$ is the basis of $W'$, then $\{e_i\otimes f_j\}$ is the basis of $\mathcal{B}(V',W')$.

|

||||

|

||||

That is, every element of $\mathcal{B}(V',W')$ can be written as a linear combination of the basis.

|

||||

|

||||

Since $\{e_i\}$ and $\{f_j\}$ are bases of $V'$ and $W'$, respectively, then we can always find a set of linear functionals $\{\phi_i\}$ and $\{\psi_j\}$ such that $\phi_i(e_j)=\delta_{ij}$ and $\psi_j(f_i)=\delta_{ij}$.

|

||||

|

||||

Here $\delta_{ij}=\begin{cases}

|

||||

1 & \text{if } i=j \\

|

||||

0 & \text{otherwise}

|

||||

\end{cases}$ is the Kronecker delta.

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

V\otimes W=\left\{\sum_{i=1}^n \sum_{j=1}^m a_{ij} \phi_i(v)\psi_j(w): \phi_i\in V', \psi_j\in W'\right\}

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

Note that $\sum_{i=1}^n \sum_{j=1}^m a_{ij} \phi_i(v)\psi_j(w)$ is a bilinear functional that maps $V'\times W'$ to $\mathbb{F}$.

|

||||

|

||||

This enables basis free construction of vector spaces with proper multiplication and scalar multiplication.

|

||||

|

||||

This vector space is equipped with the unique inner product $\langle v\otimes w, u\otimes x\rangle_{V\otimes W}$ defined by

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\langle v\otimes w, u\otimes x\rangle=\langle v,u\rangle_V\langle w,x\rangle_W

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

In practice, we ignore the subscript of the vector space and just write $\langle v\otimes w, u\otimes x\rangle=\langle v,u\rangle\langle w,x\rangle$.

|

||||

|

||||

> [!NOTE]

|

||||

>

|

||||

> All those definitions and proofs can be found in Linear Algebra Done Right by Sheldon Axler.

|

||||

|

||||

#### Definition of two-state quantum system

|

||||

|

||||

The finite dimensional Hilbert space $\mathcscr{H}

|

||||

|

||||

#### Definition of Coherent states from the view of physics

|

||||

|

||||

#### Side node: Why quantum error-correcting code is hard

|

||||

|

||||

Decoherence process

|

||||

|

||||

#### No-cloning theorem

|

||||

|

||||

> Reference from P.532 of the book

|

||||

|

||||

Suppose we have a quantum system with two slots $A$, and $B$, the data slot, starts out in an unknown but pure quantum state $\ket{\psi}$. This is the state which is to be copied into slot $B$m the target slot. We assume that the target slot starts out in some standard pure state $\ket{s}$. Thus the initial state of the copying machine is $\ket{\psi}\otimes \ket{s}$.

|

||||

|

||||

Assume there exists some unitary operator $U$ such that $U(\ket{\psi}\otimes \ket{s})=\ket{\psi}\otimes \ket{\psi}$.

|

||||

|

||||

Consider two pure states $\ket{\psi}$ and $\ket{\varphi}$, such that $U(\ket{\psi}\otimes \ket{s})=\ket{\psi}\otimes \ket{\psi}$ and $U(\ket{\varphi}\otimes \ket{s})=\ket{\varphi}\otimes \ket{\varphi}$. The inner product of the two equation yields:

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\langle \psi|\varphi\rangle =(\langle \psi|\varphi\rangle)^2

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

This equation has only two solutions, either $\langle \psi|\varphi\rangle=0$ or $\langle \psi|\varphi\rangle=1$.

|

||||

|

||||

If $\langle \psi|\varphi\rangle=0$, then $\ket{\psi}=\ket{\varphi}$, no cloning for trivial case.

|

||||

|

||||

If $\langle \psi|\varphi\rangle=1$, then $\ket{\psi}$ and $\ket{\varphi}$ are orthogonal.

|

||||

|

||||

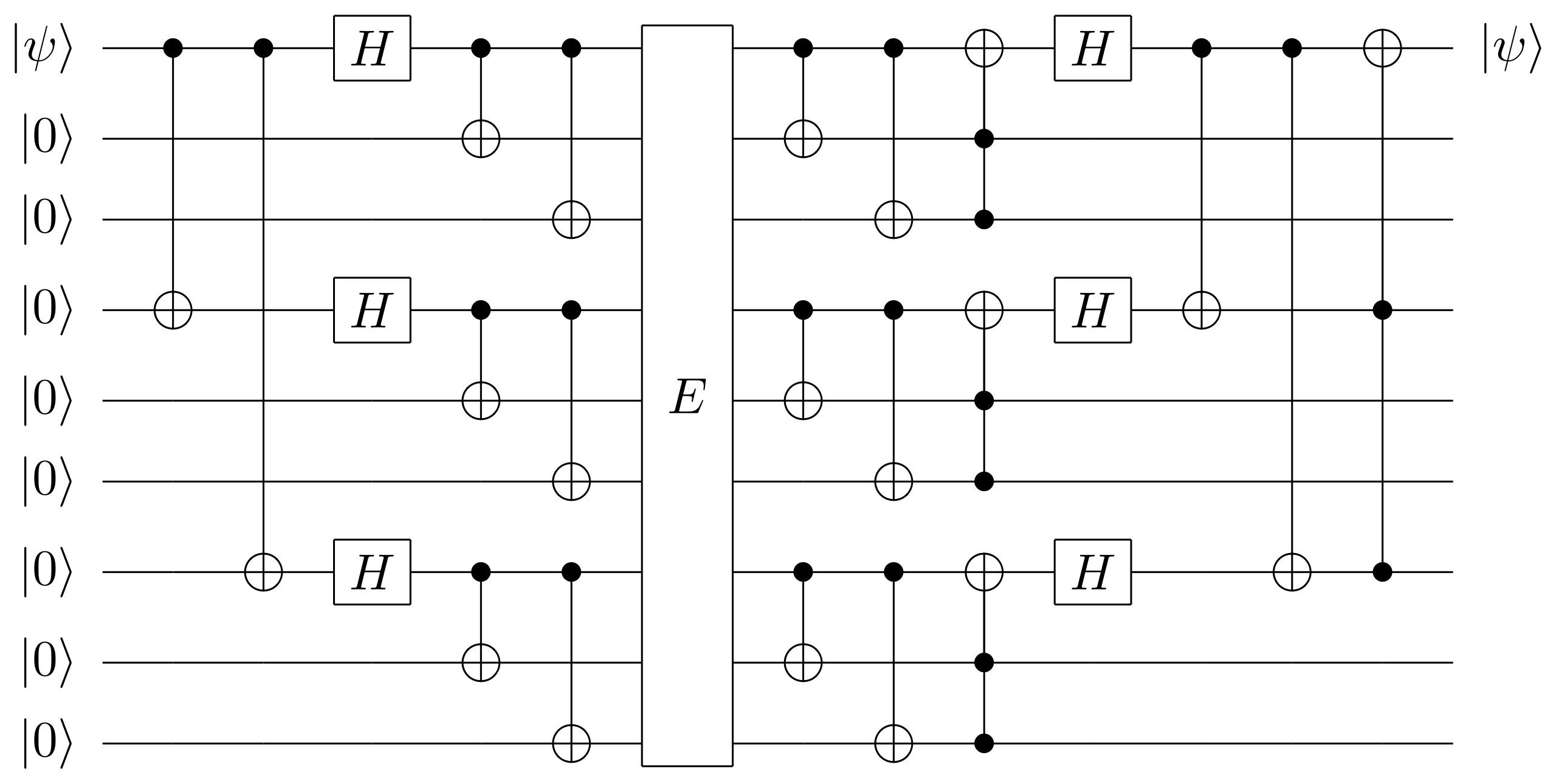

#### Proposition: Encoding 8 to 9 that correct 1 errors

|

||||

|

||||

Recover 1 qubit from a 9 qubit quantum system. (Shor code, 1995)

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

### Tools and related topics

|

||||

|

||||

#### Theoretical upper bound for quantum error-correcting code

|

||||

|

||||

From quantum information capacity of a quantum channel

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\min\{1-H_2(2t/3n),H_2(\frac{1}{2}+\sqrt{(1-t/n)t/n})\}

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

#### Definition of quantum error-correcting code from binary linear error-correcting code

|

||||

|

||||

All the operations will be done in $\mathbb{F}_2=\{0,1\}$.

|

||||

|

||||

Consider two binary vectors $v=[v_1,...,v_n],v_i\in\{0,1\}$ and $w=[w_1,...,w_n],w_i\in\{0,1\}$ with size $n$.

|

||||

|

||||

Recall from our lecture that

|

||||

|

||||

$d$ denotes the Hamming weight of a vector.

|

||||

|

||||

$d_H(v,w)=\sum_{i=1}^{n}\begin{cases} 0 & \text{if } v_i=w_i \\ 1 & \text{if } v_i\neq w_i \end{cases}$ denotes the Hamming distance between $v$ and $w$.

|

||||

|

||||

$\operatorname{supp}(v)=\{i\in[n]:v_i\neq 0\}$ denotes the support of $v$.

|

||||

|

||||

$v|_S$ denotes the projection of $v$ onto the subspace $S$, we usually denote the $S$ by a set of coordinates, that is $S\subseteq[n]$.

|

||||

|

||||

When projecting a vector $v$ onto a another vector $w$, we usually write $v|_E\coloneqq v|_{\operatorname{supp} w}$.

|

||||

|

||||

When we have two vector we may use $v\leqslant w$ (Note that this is different than $\leq$ sign) to mean $\operatorname{supp}(v)\subseteq \operatorname{supp}(w)$.

|

||||

|

||||

<details>

|

||||

<summary>Example</summary>

|

||||

|

||||

Let $v=[1,0,0,1,1,1,1]$ and $w=[1,0,0,1,0,0,1]$, then $\operatorname{supp}(v)=\{1,4,5,6,7\}$, $\operatorname{supp}(w)=\{1,4,7\}$. Therefore $w\leqslant v$.

|

||||

|

||||

$v|_w=[v_1,v_4,v_7]=[1,1,0]$

|

||||

</details>

|

||||

|

||||

$\mathcal{C}$ denotes the code, a set of arbitrary binary vectors with length $n$.

|

||||

|

||||

$d(\mathcal{C})=\{d(v,w)|v,w\in\mathcal{C}\}$ denotes the minimum distance of the code.

|

||||

|

||||

If $\mathcal{C}$ is linear then the minimum distance is the minimum Hamming weight of a non-zero codeword.

|

||||

|

||||

A $[n,k,d]$ linear code is a linear code of $n$ bits codeword with $k$ message bits that can correct $d$ errors.

|

||||

|

||||

$R\coloneqq\frac{\operatorname{dim}\mathcal{C}}{n}$ is the rate of code $\mathcal{C}$.

|

||||

|

||||

$\mathcal{C}^{\perp}\coloneqq\{v\in\mathbb{F}_2^n:v\cdot w=0\text{ for all }w\in\mathcal{C}\}$ is the dual code of a code $\mathcal{C}$. From linear algebra, we know that $\dim\mathcal{C}^{\perp}+\dim\mathcal{C}=n$.

|

||||

|

||||

<details>

|

||||

<summary>Example used in the paper</summary>

|

||||

|

||||

Consider the $[7,4,3]$ Hamming code with generator matrix $G$.

|

||||

|

||||

</details>

|

||||

|

||||

#### Proposition: Encoding $k$ to $n$ that correct $t$ errors

|

||||

|

||||

### Evaluation of paper

|

||||

|

||||

### Limitation and suggestions

|

||||

|

||||

### Further direction and research

|

||||

|

||||

#### Toric code, surface code

|

||||

|

||||

This is the topic I really want to dig into.

|

||||

|

||||

This method gives a [2nm+n+m+1, 1, min(n,m)] error correcting code with only needs local stabilizer checks and really interests me.

|

||||

|

||||

### References

|

||||

<iframe src="https://git.trance-0.com/Trance-0/CSE5313F1/raw/branch/main/latex/ZheyuanWu_CSE5313_FinalAssignment.pdf" width="100%" height="600px" style="border: none;" title="Embedded PDF Viewer">

|

||||

<!-- Fallback content for browsers that do not support iframes or PDFs within them -->

|

||||

<iframe src="https://git.trance-0.com/Trance-0/CSE5313F1/raw/branch/main/latex/ZheyuanWu_CSE5313_FinalAssignment.pdf" width="100%" height="500px">

|

||||

<p>Your browser does not support iframes. You can <a href="https://git.trance-0.com/Trance-0/CSE5313F1/raw/branch/main/latex/ZheyuanWu_CSE5313_FinalAssignment.pdf">download the PDF</a> file instead.</p>

|

||||

</iframe>

|

||||

|

||||

@@ -53,4 +53,4 @@ $$

|

||||

|

||||

This part is intentionally left blank and may be filled near the end of the semester, by assignments given in CSE5313.

|

||||

|

||||

[Link to self-contained report](../../CSE5313/Exam_reviews/CSE5313_F1.md)

|

||||

[Link to self-contained report](https://notenextra.trance-0.com/CSE5313/Exam_reviews/CSE5313_F1/)

|

||||

@@ -4,6 +4,7 @@ I made this little book for my Honor Thesis, showing the relevant parts of my wo

|

||||

|

||||

Contents updated as displayed and based on my personal interest and progress with Prof.Feres.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

<iframe src="https://git.trance-0.com/Trance-0/HonorThesis/raw/branch/main/main.pdf" width="100%" height="600px" style="border: none;" title="Embedded PDF Viewer">

|

||||

<!-- Fallback content for browsers that do not support iframes or PDFs within them -->

|

||||

<iframe src="https://git.trance-0.com/Trance-0/HonorThesis/raw/branch/main/main.pdf" width="100%" height="500px">

|

||||

|

||||

@@ -21,7 +21,7 @@ If $\mathbb{R}_l$ is second countable, then for any real number $x$, there is an

|

||||

|

||||

Any such open sets is of the form $[x,x+\epsilon)\cap A$ with $\epsilon>0$ and any element of $A$ being larger than $\min(U_x)=x$.

|

||||

|

||||

In summary, for any $x\in \mathbb{R}$, there is an element $U_x\in \mathcal{B}$ with $(U_x)=x$. In particular, if $x\neq y$, then $U_x\neq U_y$. SO there is an injective map $f:\mathbb{R}\rightarrow \mathcal{B}$ sending $x$ to $U_x$. This implies that $\mathbb{B}$ is uncountable.

|

||||

In summary, for any $x\in \mathbb{R}$, there is an element $U_x\in \mathcal{B}$ with $(U_x)=x$. In particular, if $x\neq y$, then $U_x\neq U_y$. So there is an injective map $f:\mathbb{R}\rightarrow \mathcal{B}$ sending $x$ to $U_x$. This implies that $\mathcal{B}$ is uncountable.

|

||||

|

||||

</details>

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

@@ -27,7 +27,7 @@ $$

|

||||

Let $(X,\mathcal{T})$ be a topological space. Let $\mathcal{C}\subseteq \mathcal{T}$ be a collection of subsets of $X$ satisfying the following property:

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\forall U\in \mathcal{T}, \exists C\in \mathcal{C} \text{ such that } U\subseteq C

|

||||

\forall U\in \mathcal{T}, \exists C\in \mathcal{C} \text{ such that } C\subseteq U

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

Then $\mathcal{C}$ is a basis and the topology generated by $\mathcal{C}$ is $\mathcal{T}$.

|

||||

|

||||

100

content/Math4202/Math4202_L10.md

Normal file

100

content/Math4202/Math4202_L10.md

Normal file

@@ -0,0 +1,100 @@

|

||||

# Math4202 Topology II (Lecture 10)

|

||||

|

||||

## Algebraic Topology

|

||||

|

||||

### Path homotopy

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

#### Theorem for properties of product of paths

|

||||

|

||||

1. If $f\simeq_p f_1, g\simeq_p g_1$, then $f*g\simeq_p f_1*g_1$. (Product is well-defined)

|

||||

2. $([f]*[g])*[h]=[f]*([g]*[h])$. (Associativity)

|

||||

3. Let $e_{x_0}$ be the constant path from $x_0$ to $x_0$, $e_{x_1}$ be the constant path from $x_1$ to $x_1$. Suppose $f$ is a path from $x_0$ to $x_1$.

|

||||

$$

|

||||

[e_{x_0}]*[f]=[f],\quad [f]*[e_{x_1}]=[f]

|

||||

$$

|

||||

(Right and left identity)

|

||||

4. Given $f$ in $X$ a path from $x_0$ to $x_1$, we define $\bar{f}$ to be the path from $x_1$ to $x_0$ where $\bar{f}(t)=f(1-t)$.

|

||||

$$

|

||||

f*\bar{f}=e_{x_0},\quad \bar{f}*f=e_{x_1}

|

||||

$$

|

||||

$$

|

||||

[f]*[\bar{f}]=[e_{x_0}],\quad [\bar{f}]*[f]=[e_{x_1}]

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

<details>

|

||||

<summary>Proof</summary>

|

||||

|

||||

(1) If $f\simeq_p f_1$, $g\simeq_p g_1$, then $f*g\simeq_p f_1*g_1$.

|

||||

|

||||

Let $F$ be homotopy between $f$ and $f_1$, $G$ be homotopy between $g$ and $g_1$.

|

||||

|

||||

We can define

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

F*G:[0,1]\times [0,1]\to X,\quad F*G(s,t)=\left(F(-,t)*G(-,t)\right)(s)=\begin{cases}

|

||||

F(2s,t) & 0\leq s\leq \frac{1}{2}\\

|

||||

G(2s-1,t) & \frac{1}{2}\leq s\leq 1

|

||||

\end{cases}

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

$F*G$ is a homotopy between $f*g$ and $f_1*g_1$.

|

||||

|

||||

We can check this by enumerating the cases from definition of homotopy.

|

||||

|

||||

---

|

||||

|

||||

(2) $([f]*[g])*[h]=[f]*([g]*[h])$.

|

||||

|

||||

For $f*(g*h)$, along the interval $[0,\frac{1}{2}]$ we map $x_1\to x_2$, then along the interval $[\frac{1}{2},\frac{3}{4}]$ we map $x_2\to x_3$, then along the interval $[\frac{3}{4},1]$ we map $x_3\to x_4$.

|

||||

|

||||

For $(f*g)*h$, along the interval $[0,\frac{1}{4}]$ we map $x_1\to x_2$, then along the interval $[\frac{1}{4},\frac{1}{2}]$ we map $x_2\to x_3$, then along the interval $[\frac{1}{2},1]$ we map $x_3\to x_4$.

|

||||

|

||||

We can construct the homotopy between $f*(g*h)$ and $(f*g)*h$ as follows.

|

||||

|

||||

Let $f((4-2t)s)$ for $F(s,t)$,

|

||||

|

||||

when $t=0$, $F(s,0)=f(4s)\in f*(g*h)$, when $t=1$, $F(s,1)=f(2s)\in (f*g)*h$.

|

||||

|

||||

....

|

||||

|

||||

_We make the linear maps between $f*(g*h)$ and $(f*g)*h$ continuous, then $f*(g*h)\simeq_p (f*g)*h$. With our homotopy constructed above_

|

||||

|

||||

---

|

||||

|

||||

(3) $e_{x_0}*f\simeq_p f\simeq_p f*e_{x_1}$.

|

||||

|

||||

We can construct the homotopy between $e_{x_0}*f$ and $f$ as follows.

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

H(s,t)=\begin{cases}

|

||||

x_0 & t\geq 2s\\

|

||||

f(2s-t) & t\leq 2s

|

||||

\end{cases}

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

or you may induct from $f(\frac{s-t/2}{1-t/2})$ if you like.

|

||||

|

||||

---

|

||||

|

||||

(4) $f*\bar{f}=e_{x_0},\quad \bar{f}*f=e_{x_1}$.

|

||||

|

||||

Note that we don't need to reach $x_1$ every time.

|

||||

|

||||

$f_t=f(ts)$ $s\in[0,\frac{1}{2}]$.

|

||||

|

||||

$\bar{f}_t=\bar{f}(1-ts)$ $s\in[\frac{1}{2},1]$.

|

||||

|

||||

</details>

|

||||

|

||||

> [!CAUTION]

|

||||

>

|

||||

> Homeomorphism does not implies homotopy automatically.

|

||||

|

||||

#### Definition for the fundamental group

|

||||

|

||||

The fundamental group of $X$ at $x$ is defined to be

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

(\Pi_1(X,x),*)

|

||||

$$

|

||||

132

content/Math4202/Math4202_L11.md

Normal file

132

content/Math4202/Math4202_L11.md

Normal file

@@ -0,0 +1,132 @@

|

||||

# Math4201 Topology II (Lecture 11)

|

||||

|

||||

## Algebraic topology

|

||||

|

||||

### Fundamental group

|

||||

|

||||

The $*$ operation has the following properties:

|

||||

|

||||

#### Properties for the path product operation

|

||||

|

||||

Let $[f],[g]\in \Pi_1(X)$, for $[f]\in \Pi_1(X)$, let $s:\Pi_1(X)\to X, [f]\mapsto f(0)$ and $t:\Pi_1(X)\to X, [f]\mapsto f(1)$.

|

||||

|

||||

Note that $t([f])=s([g])$, $[f]*[g]=[f*g]\in \Pi_1(X)$.

|

||||

|

||||

This also satisfies the associativity. $([f]*[g])*[h]=[f]*([g]*[h])$.

|

||||

|

||||

We have left and right identity. $[f]*[e_{t(f)}]=[f], [e_{s(f)}]*[f]=[f]$.

|

||||

|

||||

We have inverse. $[f]*[\bar{x}]=[e_{s(f)}], [\bar{x}]*[f]=[e_{t(f)}]$

|

||||

|

||||

#### Definition for Groupoid

|

||||

|

||||

Let $f,g$ be paths where $g,f:[0,1]\to X$, and consider the function of all pathes in $G$, denoted as $\mathcal{G}$,

|

||||

|

||||

Set $t:\mathcal{G}\to X$ be the source map, for this case $t(f)=f(0)$, and $s:\mathcal{G}\to X$ be the target map, for this case $s(f)=f(1)$.

|

||||

|

||||

We define

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\mathcal{G}^{(2)}=\{(f,g)\in \mathcal{G}\times \mathcal{G}|t(f)=s(g)\}

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

And we define the operation $*$ on $\mathcal{G}^{(2)}$ as the path product.

|

||||

|

||||

This satisfies the following properties:

|

||||

|

||||

- Associativity: $(f*g)*h=f*(g*h)$

|

||||

|

||||

Consider the function $\eta:X\to \mathcal{G}$, for this case $\eta(x)=e_{x}$.

|

||||

|

||||

- We have left and right identity: $\eta(t(f))*f=f, f*\eta(s(f))=f$

|

||||

|

||||

- Inverse: $\forall g\in \mathcal{G}, \exists g^{-1}\in \mathcal{G}, g*g^{-1}=\eta(s(g))$, $g^{-1}*g=\eta(t(g))$

|

||||

|

||||

#### Definition for loop

|

||||

|

||||

Let $x_0\in X$. A path starting and ending at $x_0$ is called a loop based at $x_0$.

|

||||

|

||||

#### Definition for the fundamental group

|

||||

|

||||

The fundamental group of $X$ at $x$ is defined to be

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

(\Pi_1(X,x),*)

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

where $*$ is the product operation, and $\Pi_1(X,x)$ is the set o homotopy classes of loops in $X$ based at $x$.

|

||||

|

||||

<details>

|

||||

<summary>Example of fundamental group</summary>

|

||||

|

||||

Consider $X=[0,1]$, with subspace topology from standard topology in $\mathbb{R}$.

|

||||

|

||||

$\Pi_1(X,0)=\{e\}$, (constant function at $0$) since we can build homotopy for all loops based at $0$ as follows $H(s,t)=(1-t)f(s)+t$.

|

||||

|

||||

And $\Pi_1(X,1)=\{e\}$, (constant function at $1$.)

|

||||

|

||||

---

|

||||

|

||||

Let $X=\{1,2\}$ with discrete topology.

|

||||

|

||||

$\Pi_1(X,1)=\{e\}$, (constant function at $1$.)

|

||||

|

||||

$\Pi_1(X,2)=\{e\}$, (constant function at $2$.)

|

||||

|

||||

---

|

||||

|

||||

Let $X=S^1$ be the circle.

|

||||

|

||||

$\Pi_1(X,1)=\mathbb{Z}$ (related to winding numbers, prove next week).

|

||||

|

||||

</details>

|

||||

|

||||

A natural question is, will the fundamental group depends on the basepoint $x$?

|

||||

|

||||

#### Definition for $\hat{\alpha}$

|

||||

|

||||

Let $\alpha$ be a path in $X$ from $x_0$ to $x_1$. $\alpha:[0,1]\to X$ such that $\alpha(0)=x_0$ and $\alpha(1)=x_1$. Define $\hat{\alpha}:\Pi_1(X,x_0)\to \Pi_1(X,x_1)$ as follows:

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\hat{\alpha}(\beta)=[\bar{\alpha}]*[f]*[\alpha]

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

#### $\hat{\alpha}$ is a group homomorphism

|

||||

|

||||

$\hat{\alpha}$ is a group homomorphism between $(\Pi_1(X,x_0),*)$ and $(\Pi_1(X,x_1),*)$

|

||||

|

||||

<details>

|

||||

<summary>Proof</summary>

|

||||

|

||||

Let $f,g\in \Pi_1(X,x_0)$, then $\hat{\alpha}(f*g)=\hat{\alpha}(f)\hat{\alpha}(g)$

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\begin{aligned}

|

||||

\hat{\alpha}(f*g)&=[\bar{\alpha}]*[f]*[g]*[\alpha]\\

|

||||

&=[\bar{\alpha}]*[f]*[e_{x_0}]*[g]*[\alpha]\\

|

||||

&=[\bar{\alpha}]*[f]*[\alpha]*[\bar{\alpha}]*[g]*[\alpha]\\

|

||||

&=([\bar{\alpha}]*[f]*[\alpha])*([\bar{\alpha}]*[g]*[\alpha])\\

|

||||

&=(\hat{\alpha}(f))*(\hat{\alpha}(g))

|

||||

\end{aligned}

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

---

|

||||

|

||||

Next, we will show that $\hat{\alpha}\circ \hat{\bar{\alpha}}([f])=[f]$, and $\hat{\bar{\alpha}}\circ \hat{\alpha}([f])=[f]$.

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\begin{aligned}

|

||||

\hat{\alpha}\circ \hat{\bar{\alpha}}([f])&=\hat{\alpha}([\bar{\alpha}]*[f]*[\alpha])\\

|

||||

&=[\alpha]*[\bar{\alpha}]*[f]*[\alpha]*[\bar{\alpha}]\\

|

||||

&=[e_{x_0}]*[f]*[e_{x_1}]\\

|

||||

&=[f]

|

||||

\end{aligned}

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

The other case is the same

|

||||

|

||||

</details>

|

||||

|

||||

#### Corollary of fundamental group

|

||||

|

||||

If $X$ is path-connected and $x_0,x_1\in X$, then $\Pi_1(X,x_0)$ is isomorphic to $\Pi_1(X,x_1)$.

|

||||

119

content/Math4202/Math4202_L12.md

Normal file

119

content/Math4202/Math4202_L12.md

Normal file

@@ -0,0 +1,119 @@

|

||||

# Math4201 Topology II (Lecture 12)

|

||||

|

||||

## Algebraic topology

|

||||

|

||||

### Fundamental group

|

||||

|

||||

Recall from last lecture, the $(\Pi_1(X,x_0),*)$ is a group, and for any two points $x_0,x_1\in X$, the group $(\Pi_1(X,x_0),*)$ is isomorphic to $(\Pi_1(X,x_1),*)$ if $x_0,x_1$ is path connected.

|

||||

|

||||

> [!TIP]

|

||||

>

|

||||

> How does the $\hat{\alpha}$ (isomorphism between $(\Pi_1(X,x_0),*)$ and $(\Pi_1(X,x_1),*)$) depend on the choice of $\alpha$ (path) we choose?

|

||||

|

||||

#### Definition of simply connected

|

||||

|

||||

A space $X$ is simply connected if

|

||||

|

||||

- $X$ is [path-connected](https://notenextra.trance-0.com/Math4201/Math4201_L23/#definition-of-path-connected-space) ($\forall x_0,x_1\in X$, there exists a continuous function $\alpha:[0,1]\to X$ such that $\alpha(0)=x_0$ and $\alpha(1)=x_1$)

|

||||

- $\Pi_1(X,x_0)$ is the trivial group for some $x_0\in X$

|

||||

|

||||

<details>

|

||||

<summary>Example of simply connected space</summary>

|

||||

|

||||

Intervals are simply connected.

|

||||

|

||||

---

|

||||

|

||||

Any star-shaped is simply connected.

|

||||

|

||||

---

|

||||

|

||||

$S^1$ is not simply connected, but $n\geq 2$, then $S^n$ is simply connected.

|

||||

|

||||

</details>

|

||||

|

||||

#### Lemma for simply connected space

|

||||

|

||||

In a simply connected space $X$, and two paths having the same initial and final points are path homotopic.

|

||||

|

||||

<details>

|

||||

<summary>Proof</summary>

|

||||

|

||||

Let $f,g$ be paths having the same initial and final points, then $f(0)=g(0)=x_0$ and $f(1)=g(1)=x_1$.

|

||||

|

||||

Therefore $[f]*[\bar{g}]\simeq_p [e_{x_0}]$ (by simply connected space assumption).

|

||||

|

||||

Then

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\begin{aligned}

|

||||

[f]*[\bar{g}]&\simeq_p [e_{x_0}]\\

|

||||

([f]*[\bar{g}])*[g]&\simeq_p [e_{x_0}]*[g]\\

|

||||

[f]*([\bar{g}]*[g])&\simeq_p [e_{x_0}]*[g]\\

|

||||

[f]*[e_{x_1}]&\simeq_p [e_{x_0}]*[g]\\

|

||||

[f]&\simeq_p [g]

|

||||

\end{aligned}

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

</details>

|

||||

|

||||

#### Definition of group homomorphism induced by continuous map

|

||||

|

||||

Let $h:(X,x_0)\to (Y,y_0)$ be a continuous map, define $h_*:\Pi_1(X,x_0)\to \Pi_1(Y,y_0)$ where $h(x_0)=y_0$. by $h_*([f])=[h\circ f]$.

|

||||

|

||||

$h_*$ is called the group homomorphism induced by $h$ relative to $x_0$.

|

||||

|

||||

<details>

|

||||

<summary>Check the homomorphism property</summary>

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\begin{aligned}

|

||||

h_*([f]*[g])&=h_*([f*g])\\

|

||||

&=[h_*[f*g]]\\

|

||||

&=[h_*[f]*h_*[g]]\\

|

||||

&=[h_*[f]]*[h_*[g]]\\

|

||||

&=h_*([f])*h_*([g])

|

||||

\end{aligned}

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

</details>

|

||||

|

||||

#### Theorem composite of group homomorphism

|

||||

|

||||

If $h:(X,x_0)\to (Y,y_0)$ and $k:(Y,y_0)\to (Z,z_0)$ are continuous maps, then $k_* \circ h_*:\Pi_1(X,x_0)\to \Pi_1(Z,z_0)$ where $h_*:\Pi_1(X,x_0)\to \Pi_1(Y,y_0)$, $k_*:\Pi_1(Y,y_0)\to \Pi_1(Z,z_0)$,is a group homomorphism.

|

||||

|

||||

<details>

|

||||

<summary>Proof</summary>

|

||||

|

||||

Let $f$ be a loop based at $x_0$.

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\begin{aligned}

|

||||

k_*(h_*([f]))&=k_*([h\circ f])\\

|

||||

&=[k\circ h\circ f]\\

|

||||

&=[(k\circ h)\circ f]\\

|

||||

&=(k\circ h)_*([f])\\

|

||||

\end{aligned}

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

</details>

|

||||

|

||||

#### Corollary of composite of group homomorphism

|

||||

|

||||

Let $\operatorname{id}:(X,x_0)\to (X,x_0)$ be the identity map. This induces $(\operatorname{id})_*:\Pi_1(X,x_0)\to \Pi_1(X,x_0)$.

|

||||

|

||||

If $h$ is a homeomorphism with the inverse $k$, with

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

k_*\circ h_*=(k\circ h)_*=(\operatorname{id})_*=I=(\operatorname{id})_*=(h\circ k)_*

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

This induced $h_*: \Pi_1(X,x_0)\to \Pi_1(Y,y_0)$ is an isomorphism.

|

||||

|

||||

#### Corollary for homotopy and group homomorphism

|

||||

|

||||

If $h,k:(X,x_0)\to (Y,y_0)$ are homotopic maps form $X$ to $Y$ such that the homotopy $H_t(x_0)=y_0,\forall t\in I$, then $h_*=k_*$.

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

h_*([f])=[h\circ f]\simeq_p[k\circ h]=k_*([f])

|

||||

$$

|

||||

59

content/Math4202/Math4202_L13.md

Normal file

59

content/Math4202/Math4202_L13.md

Normal file

@@ -0,0 +1,59 @@

|

||||

# Math4202 Topology II (Lecture 13)

|

||||

|

||||

## Algebraic Topology

|

||||

|

||||

### Covering space

|

||||

|

||||

#### Definition of partition into slice

|

||||

|

||||

Let $p:E\to B$ be a continuous surjective map. The open set $U\subseteq B$ is said to be evenly covered by $p$ if it's inverse image $p^{-1}(U)$ can be written as the union of **disjoint open sets** $V_\alpha$ in $E$. Such that for each $\alpha$, the restriction of $p$ to $V_\alpha$ is a homeomorphism of $V_\alpha$ onto $U$.

|

||||

|

||||

The collection of $\{V_\alpha\}$ is called a **partition** $p^{-1}(U)$ into slice.

|

||||

|

||||

_Stack of pancakes ($\{V_\alpha\}$) on plate $U$, each $V_\alpha$ is a pancake homeomorphic to $U$_

|

||||

|

||||

_Note that all the sets in the definition are open._

|

||||

|

||||

#### Definition of covering space

|

||||

|

||||

Let $p:E\to B$ be a continuous surjective map. If every point $b$ of $B$ has a neighborhood **evenly covered** by $p$, which means $p^{-1}(U)$ is partitioned into slice, then $p$ is called a covering map and $E$ is called a covering space.

|

||||

|

||||

<details>

|

||||

<summary>Examples of covering space</summary>

|

||||

|

||||

identity map is a covering map

|

||||

|

||||

---

|

||||

|

||||

Consider the $B\times \Gamma\to B$ with $\Gamma$ being the discrete topology with the projection map onto $B$.

|

||||

|

||||

This is a covering map.

|

||||

|

||||

---

|

||||

|

||||

Let $S^1=\{z\mid |z|=1\}$, then $p=z^n$ is a covering map to $S^1$.

|

||||

|

||||

Solving the inverse image for the $e^{i\theta}$ with $\epsilon$ interval, we can get $n$ slices for each neighborhood of $e^{i\theta}$, $-\epsilon< \theta< \epsilon$.

|

||||

|

||||

You can continue the computation and find the exact $\epsilon$ so that the inverse image of $p^{-1}$ is small and each interval don't intersect (so that we can make homeomorphism for each interval).

|

||||

|

||||

Usually, we don't choose the $U$ to be the whole space.

|

||||

|

||||

---

|

||||

|

||||

Consider the projection for the boundary of mobius strip into middle circle.

|

||||

|

||||

This is a covering map since the boundary of mobius strip is winding the middle circle twice, and for each point on the middle circle with small enough neighborhood, there will be two disjoint interval on the boundary of mobius strip that are homeomorphic to the middle circle.

|

||||

|

||||

</details>

|

||||

|

||||

#### Proposition of covering map is open map

|

||||

|

||||

If $p:E\to B$ is a covering map, then $p$ is an open map.

|

||||

|

||||

<details>

|

||||

<summary>Proof</summary>

|

||||

|

||||

Consider arbitrary open set $V\subseteq E$, consider $U=p(V)$, for every point $q\in U$, with neighborhood $q\in W$, the inverse image of $W$ is open, continue next lecture.

|

||||

|

||||

</details>

|

||||

@@ -1,4 +1,4 @@

|

||||

# Math4202 Topology II (Lecture 5)

|

||||

# Math4202 Topology II (Lecture 6)

|

||||

|

||||

## Manifolds

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

63

content/Math4202/Math4202_L7.md

Normal file

63

content/Math4202/Math4202_L7.md

Normal file

@@ -0,0 +1,63 @@

|

||||

# Math4202 Topology II (Lecture 7)

|

||||

|

||||

## Algebraic Topology

|

||||

|

||||

Classify 2-dimensional topological manifolds (connected) up to homeomorphism/homotopy equivalence.

|

||||

|

||||

Use fundamental groups.

|

||||

|

||||

We want to show that:

|

||||

|

||||

1. The fundamental group is invariant under the equivalence relation.

|

||||

2. develop some methods to compute the groups.

|

||||

3. 2-dimensional topological spaces with the same fundamental group are equivalent (homeomorphism).

|

||||

|

||||

### Homotopy of paths

|

||||

|

||||

#### Definition of path

|

||||

|

||||

If $f$ and $f'$ are two continuous maps from $X$ to $Y$, where $X$ and $Y$ are topological spaces. Then we say that $f$ is homotopic to $f'$ if there exists a continuous map $F:X\times [0,1]\to Y$ such that $F(x,0)=f(x)$ and $F(x,1)=f'(x)$ for all $x\in X$.

|

||||

|

||||

The map $F$ is called a homotopy between $f$ and $f'$.

|

||||

|

||||

We use $f\simeq f'$ to mean that $f$ is homotopic to $f'$.

|

||||

|

||||

#### Definition of homotopic equivalence map

|

||||

|

||||

Let $f:X\to Y$ and $g:Y\to X$ be two continuous maps. If $f\circ g:Y\to Y$ and $g\circ f:X\to X$ are homotopic to the identity maps $\operatorname{id}_Y$ and $\operatorname{id}_X$, then $f$ and $g$ are homotopic equivalence maps. And the two spaces $X$ and $Y$ are homotopy equivalent.

|

||||

|

||||

> [!NOTE]

|

||||

>

|

||||

> This condition is weaker than homeomorphism. (In homeomorphism, let $g=f^{-1}$, we require $g\circ f=\operatorname{id}_X$ and $f\circ g=\operatorname{id}_Y$.)

|

||||

|

||||

<details>

|

||||

<summary>Example of homotopy equivalence maps</summary>

|

||||

|

||||

Let $X=\{a\}$ and $Y=[0,1]$ with standard topology.

|

||||

|

||||

Consider $f:X\to Y$ by $f(a)=0$ and $g:Y\to X$ by $g(y)=a$, where $y\in [0,1]$.

|

||||

|

||||

$g\circ f=\operatorname{id}_X$ and $f\circ g=[0,1]\mapsto 0$.

|

||||

|

||||

$g\circ f\simeq \operatorname{id}_X$

|

||||

|

||||

and $f\circ g\simeq \operatorname{id}_Y$.

|

||||

|

||||

Consider $F:X\times [0,1]\to Y$ by $F(a,0)=0$ and $F(a,t)=(1-t)y$. $F$ is continuous and homotopy between $f\circ g$ and $\operatorname{id}_Y$.

|

||||

|

||||

This gives example of homotopy but not homeomorphism.

|

||||

|

||||

</details>

|

||||

|

||||

#### Definition of null homology

|

||||

|

||||

If $f:X\to Y$ is homotopy to a constant map. $f$ is called null homotopy.

|

||||

|

||||

#### Definition of path homotopy

|

||||

|

||||

Let $f,f':I\to X$ be a continuous maps from an interval $I=[0,1]$ to a topological space $X$.

|

||||

|

||||

Two pathes $f$ and $f'$ are path homotopic if

|

||||

|

||||

- there exists a continuous map $F:I\times [0,1]\to X$ such that $F(i,0)=f(i)$ and $F(i,1)=f'(i)$ for all $i\in I$.

|

||||

- $F(s,0)=f(0)$ and $F(s,1)=f(1)$, $\forall s\in I$.

|

||||

88

content/Math4202/Math4202_L8.md

Normal file

88

content/Math4202/Math4202_L8.md

Normal file

@@ -0,0 +1,88 @@

|

||||

# Math4202 Topology II (Lecture 8)

|

||||

|

||||

## Algebraic Topology

|

||||

|

||||

### Path homotopy

|

||||

|

||||

#### Recall definition of path homotopy

|

||||

|

||||

Let $f,f':I\to X$ be a continuous maps from an interval $I=[0,1]$ to a topological space $X$.

|

||||

|

||||

Two pathes $f$ and $f'$ are path homotopic if

|

||||

|

||||

- there exists a continuous map $F:I\times [0,1]\to X$ such that $F(i,0)=f(i)$ and $F(i,1)=f'(i)$ for all $i\in I$.

|

||||

- $F(s,0)=f(0)$ and $F(s,1)=f(1)$, $\forall s\in I$.$F(s,0)=f(0)$ and $F(s,1)=f(1)$, $\forall s\in I$

|

||||

|

||||

#### Lemma: Homotopy defines an equivalence relation

|

||||

|

||||

The $\simeq$, $\simeq_p$ are both equivalence relations.

|

||||

|

||||

<details>

|

||||

<summary>Proof</summary>

|

||||

|

||||

**Reflexive**:

|

||||

|

||||

$f:I\to X$, $F:I\times I\to X$, $F(s,t)=f(s)$.

|

||||

|

||||

$F$ is a homotopy between $f$ and $f$ itself.

|

||||

|

||||

**Symmetric**:

|

||||

|

||||

Suppose $f,g:I\to X$,

|

||||

|

||||

$F:I\times I\to X$ is a homotopy between $f$ and $g$.

|

||||

|

||||

Let $H: I\times I\to X$ be a homotopy between $g$ and $f$ defined as follows:

|

||||

|

||||

$H(s,t)=F(s,1-t)$.

|

||||

|

||||

$H(s,0)=F(s,1)=g(s)$, $H(s,1)=F(s,0)=f(s)$.

|

||||

|

||||

Therefore $H$ is a homotopy between $g$ and $f$.

|

||||

|

||||

**Transitive**:

|

||||

|

||||

Suppose we have $f\simeq_p g$ with homotopy $F_1$, and $g\simeq_p h$ with homotopy $F_2$.

|

||||

|

||||

Then we can glue the two homotopies together to get a homotopy $F$ between $f$ and $h$ using pasting lemma.

|

||||

|

||||

$F(s,t)=(F_1*F_2)(s,t)\coloneqq\begin{cases}

|

||||

F_1(s,2t), & t\in [0,\frac{1}{2}]\\

|

||||

F_2(s,2t-1), & t\in [\frac{1}{2},1]

|

||||

\end{cases}$

|

||||

|

||||

Therefore $f\simeq_p h$ with homotopy $F$.

|

||||

|

||||

</details>

|

||||

|

||||

> [!NOTE]

|

||||

>

|

||||

> We use $[x]$ to denote the equivalence class of $x$.

|

||||

|

||||

<details>

|

||||

<summary>Example of equivalence classes in path homotopy</summary>

|

||||

|

||||

Let $X=\{pt\}$, $\operatorname{Path}(X)=\{\text{constant map}\}$.$\operatorname{Path}/_{\simeq_p}(X)=\{[\text{constant map}]\}$.

|

||||

|

||||

---

|

||||

|

||||

$X=\{p,q\}$ with discrete topology, $\operatorname{Path}(X)=\{f_{p},f_{q}\}$.$\operatorname{Path}/_{\simeq_p}(X)=\{[f_{p}], [f_{q}]\}$

|

||||

|

||||

This applied to all discrete topological spaces.

|

||||

|

||||

---

|

||||

|

||||

Let $X=\mathbb{R}$ with standard topology.

|

||||

|

||||

$\operatorname{Path}(X)=\{f:[0,1]\to \mathbb{R}\in C^0\}$

|

||||

|

||||

Let $f_1,f_2:[0,1]\to \mathbb{R}$ where $f_1(0)=f_2(0)$, $f_1(1)=f_2(1)$.

|

||||

|

||||

Then we can construct a homotopy between $f_1$ and $f_2$.

|

||||

|

||||

$F:[0,1]\times [0,1]\to \mathbb{R}$, $F(s,t)=(1-t)f_1(s)+tf_2(s)$ is a homotopy between $f_1$ and $f_2$.

|

||||

|

||||

$\operatorname{Path}/_{\simeq_p}(X)=\{(x_1,x_1)|x_1,x_2\in \mathbb{R}\}$

|

||||

|

||||

This applies to any convex space $V$ in $\mathbb{R}^n$.

|

||||

</details>

|

||||

145

content/Math4202/Math4202_L9.md

Normal file

145

content/Math4202/Math4202_L9.md

Normal file

@@ -0,0 +1,145 @@

|

||||

# Math4202 Topology II (Lecture 9)

|

||||

|

||||

## Algebraic Topology

|

||||

|

||||

### Path homotopy

|

||||

|

||||

Consider the space of paths up to homotopy equivalence.

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\operatorname{Path}/\simeq_p(X) =\Pi_1(X)

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

We want to impose some group structure on $\operatorname{Path}/\simeq_p(X)$.

|

||||

|

||||

Consider the $*$ operation on $\operatorname{Path}/\simeq_p(X)$.

|

||||

|

||||

Let $f,g:[0,1]\to X$ be two paths, where $f(0)=a$, $f(1)=g(0)=b$ and $g(1)=c$.

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

f*g:[0,1]\to X,\quad f*g(t)=\begin{cases}

|

||||

f(2t) & 0\leq t\leq \frac{1}{2}\\

|

||||

g(2t-1) & \frac{1}{2}\leq t\leq 1

|

||||

\end{cases}

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

This connects our two paths.

|

||||

|

||||

#### Definition for product of paths

|

||||

|

||||

Given $f$ a path in $X$ from $x_0$ to $x_1$ and $g$ a path in $X$ from $x_1$ to $x_2$.

|

||||

|

||||

Define the product $f*g$ of $f$ and $g$ to be the map $h:[0,1]\to X$.

|

||||

|

||||

#### Definition for equivalent classes of paths

|

||||

|

||||

$\Pi_1(X,x)$ is the equivalent classes of paths starting and ending at $x$.

|

||||

|

||||

On $\Pi_1(X,x)$,, we define $\forall [f],[g],[f]*[g]=[f*g]$.

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

[f]\coloneqq \{f_i:[0,1]\to X|f_0(0)=f(0),f_i(1)=f(1)\}

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

#### Lemma

|

||||

|

||||

If we have some path $k:X\to Y$ is a continuous map, and if $F$ is path homotopy between $f$ and $f'$ in $X$, then $k\circ F$ is path homotopy between $k\circ f$ and $k\circ f'$ in $Y$.

|

||||

|

||||

If $k:X\to Y$ is a continuous map, and $f,g$ are two paths in $X$ with $f(1)=g(0)$, then

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

(k\circ f)*(k\circ g)=k\circ(f*g)

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

<details>

|

||||

<summary>Proof</summary>

|

||||

|

||||

We check the definition of path homotopy.

|

||||

|

||||

$k\circ F:I\times I\to Y$ is continuous.

|

||||

|

||||

$k\circ F(s,0)=k(F(s,0))=k(f(s))=k\circ f(s)$.

|

||||

|

||||

$k\circ F(s,1)=k(F(s,1))=k(f'(s))=k\circ f'(s)$.

|

||||

|

||||

$k\circ F(0,t)=k(F(0,t))=k(f(0))=k(x_0$.

|

||||

|

||||

$k\circ F(1,t)=k(F(1,t))=k(f'(1))=k(x_1)$.

|

||||

|

||||

Therefore $k\circ F$ is path homotopy between $k\circ f$ and $k\circ f'$ in $Y$.

|

||||

|

||||

---

|

||||

|

||||

For the second part of the lemma, we proceed from the definition.

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

(k\circ f)*(k\circ g)(t)=\begin{cases}

|

||||

k\circ f(2t) & 0\leq t\leq \frac{1}{2}\\

|

||||

k\circ g(2t-1) & \frac{1}{2}\leq t\leq 1

|

||||

\end{cases}

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

and

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

k\circ(f*g)=k(f*g(t))=k\left(\begin{cases}

|

||||

f(2t) & 0\leq t\leq \frac{1}{2}\\

|

||||

g(2t-1) & \frac{1}{2}\leq t\leq 1

|

||||

\end{cases}\right)=\begin{cases}

|

||||

k(f(2t))=k\circ f(2t) & 0\leq t\leq \frac{1}{2}\\

|

||||

k(g(2t-1))=k\circ g(2t-1) & \frac{1}{2}\leq t\leq 1

|

||||

\end{cases}

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

</details>

|

||||

|

||||

#### Theorem for properties of product of paths

|

||||

|

||||

1. If $f\simeq_p f_1, g\simeq_p g_1$, then $f*g\simeq_p f_1*g_1$. (Product is well-defined)

|

||||

2. $([f]*[g])*[h]=[f]*([g]*[h])$. (Associativity)

|

||||