update

This commit is contained in:

@@ -1 +1,224 @@

|

|||||||

# CSE332S Lecture 13

|

# CSE332S Lecture 13

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

## Copy control

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Copy control consists of 5 distinct operations

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

- A `copy constructor` initializes an object by duplicating the const l-value that was passed to it by reference

|

||||||

|

- A `copy-assignment operator` (re)sets an object's value by duplicating the const l-value passed to it by reference

|

||||||

|

- A `destructor` manages the destruction of an object

|

||||||

|

- A `move constructor` initializes an object by transferring the implementation from the r-value reference passed to it (next lecture)

|

||||||

|

- A `move-assignment operator` (re)sets an object's value by transferring the implementation from the r-value reference passed to it (next lecture)

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Today we'll focus on the first 3 operations and will defer the others (introduced in C++11) until next time

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

- The others depend on the new C++11 `move semantics`

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### Basic copy control operations

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

A copy constructor or copy-assignment operator takes a reference to a (usually const) instance of the class

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

- Copy constructor initializes a new object from it

|

||||||

|

- Copy-assignment operator sets object's value from it

|

||||||

|

- In either case, original the object is left unchanged (which differs from the move versions of these operations)

|

||||||

|

- Destructor takes no arguments `~A()` (except implicit `this`)

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Copy control operations for built-in types

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

- Copy construction and copy-assignment copy values

|

||||||

|

- Destructor of built-in types does nothing (is a "no-op")

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Compiler-synthesized copy control operations

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

- Just call that same operation on each member of the object

|

||||||

|

- Uses defined/synthesized definition of that operation for user-defined types (see above for built-in types)

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### Preventing or Allowing Basic Copy Control

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Old (C++03) way to prevent compiler from generating a default constructor, copy constructor, destructor, or assignment operator was somewhat awkward

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

- Declare private, don't define, don't use within class

|

||||||

|

- This works, but gives cryptic linker error if operation is used

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

New (C++11) way to prevent calls to any method

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

- End the declaration with `= delete` (and don't define)

|

||||||

|

- Compiler will then give an intelligible error if a call is made

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

C++11 allows a constructor to call peer constructors

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

- Allows re-use of implementation (through delegation)

|

||||||

|

- Object is fully constructed once any constructor finishes

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

C++11 lets you ask compiler to synthesize operations

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

- Explicitly, but only for basic copy control, default constructor

|

||||||

|

- End the declaration with `= default` (and don't define) The compiler will then generate the operation or throw an error if it can't.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

## Shallow vs Deep Copy

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### Shallow Copy Construction

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

```cpp

|

||||||

|

// just uses the array that's already in the other object

|

||||||

|

IntArray::IntArray(const IntArray &a)

|

||||||

|

:size_(a.size_),

|

||||||

|

values_(a.values_) {

|

||||||

|

// only memory address is copied, not the memory it points to

|

||||||

|

}

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

int main(int argc, char * argv[]){

|

||||||

|

IntArray arr = {0,1,2};

|

||||||

|

IntArray arr2 = arr;

|

||||||

|

return 0;

|

||||||

|

}

|

||||||

|

```

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

There are two ways to "copy"

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

- Shallow: re-aliases existing resources

|

||||||

|

- E.g., by copying the address value from a pointer member variable

|

||||||

|

- Deep: makes a complete and separate copy

|

||||||

|

- I.e., by following pointers and deep copying what they alias

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Version above shows shallow copy

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

- Efficient but may be risky (why?) The destructor will delete the memory that the other object is pointing to.

|

||||||

|

- Usually want no-op destructor, aliasing via `shared_ptr` or a boolean value to check if the object is the original memory allocator for the resource.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### Deep Copy Construction

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

```cpp

|

||||||

|

IntArray::IntArray(const IntArray &a)

|

||||||

|

:size_(0), values_(nullptr) {

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

if (a.size_ > 0) {

|

||||||

|

// new may throw bad_alloc,

|

||||||

|

// set size_ after it succeeds

|

||||||

|

values_ = new int[a.size_];

|

||||||

|

size_ = a.size_;

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

// could use memcpy instead

|

||||||

|

for (size_t i = 0;

|

||||||

|

i < size_; ++i) {

|

||||||

|

values_[i] = a.values_[i];

|

||||||

|

}

|

||||||

|

}

|

||||||

|

}

|

||||||

|

int main(int argc, char * argv[]){

|

||||||

|

IntArray arr = {0,1,2};

|

||||||

|

IntArray arr2 = arr;

|

||||||

|

return 0;

|

||||||

|

}

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

```

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

This code shows deep copy

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

- Safe: no shared aliasing, exception aware initialization

|

||||||

|

- But may not be as efficient as shallow copy in many cases

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Note trade-offs with arrays

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

- Allocate memory once

|

||||||

|

- More efficient than multiple calls to new (heap search)

|

||||||

|

- Constructor and assignment called on each array element

|

||||||

|

- Less efficient than block copy

|

||||||

|

- E.g., using `memcpy()`

|

||||||

|

- But sometimes necessary

|

||||||

|

- i.e., constructors, destructors establish needed invariants

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Each object is responsible for its own resources.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

## Swap Trick for Copy-Assignment

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

The swap trick is a way to implement the copy-assignment operator, given that the `size_` and `values_` members are already defined in constructor.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

```cpp

|

||||||

|

class Array {

|

||||||

|

public:

|

||||||

|

Array(unsigned int) ; // assume constructor allocates memory

|

||||||

|

Array(const Array &); // assume copy constructor makes a deep copy

|

||||||

|

~Array(); // assume destructor calls delete on values_

|

||||||

|

Array & operator=(const Array &a);

|

||||||

|

private:

|

||||||

|

size_t size_;

|

||||||

|

int * values_;

|

||||||

|

};

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Array & Array::operator=(const Array &a) { // return ref lets us chain

|

||||||

|

if (&a != this) { // note test for self-assignment (safe, efficient)

|

||||||

|

Array temp(a); // copy constructor makes deep copy of a

|

||||||

|

swap(temp.size_, size_); // note unqualified calls to swap

|

||||||

|

swap(temp.values_, values_); // (do user-defined or std::swap)

|

||||||

|

}

|

||||||

|

return *this; // previous *values_ cleaned up by temp's destructor, which is the member variable of the current object

|

||||||

|

}

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

int main(int argc, char * argv[]){

|

||||||

|

IntArray arr = {0,1,2};

|

||||||

|

IntArray arr2 = {3,4,5};

|

||||||

|

arr2 = arr;

|

||||||

|

return 0;

|

||||||

|

}

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

```

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

## Review: Construction/destruction order with inheritance, copy control with inheritance

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### Constructor and Destructor are Inverses

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

```cpp

|

||||||

|

IntArray::IntArray(unsigned int u)

|

||||||

|

: size_(0), values_(nullptr) {

|

||||||

|

// exception safe semantics

|

||||||

|

values_ = new int [u];

|

||||||

|

size_ = u;

|

||||||

|

}

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

IntArray::~IntArray() {

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

// deallocates heap memory

|

||||||

|

// that values_ points to,

|

||||||

|

// so it's not leaked:

|

||||||

|

// with deep copy, object

|

||||||

|

// owns the memory

|

||||||

|

delete [] values_;

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

// the size_ and values_

|

||||||

|

// member variables are

|

||||||

|

// themselves destroyed

|

||||||

|

// after destructor body

|

||||||

|

}

|

||||||

|

```

|

||||||

|

Constructors initialize

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

- At the start of each object's lifetime

|

||||||

|

- Implicitly called when object is created

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Destructors clean up

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

- Implicitly called when an object is destroyed

|

||||||

|

- E.g., when stack frame where it was declared goes out of scope

|

||||||

|

- E.g., when its address is passed to delete

|

||||||

|

- E.g., when another object of which it is a member is being destroyed

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### More on Initialization and Destruction

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Initialization follows a well defined order

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

- Base class constructor is called

|

||||||

|

- That constructor recursively follows this order, too

|

||||||

|

- Member constructors are called

|

||||||

|

- In order members were declared

|

||||||

|

- Good style to list in that order (a good compiler may warn if not)

|

||||||

|

- Constructor body is run

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Destruction occurs in the reverse order

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

- Destructor body is run, then member destructors, then base class destructor (which recursively follows reverse order)

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

**Make destructor virtual if members are virtual**

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

- Or if class is part of an inheritance hierarchy

|

||||||

|

- Avoids “slicing”: ensures destruction starts at the most derived class destructor (not at some higher base class)

|

||||||

|

|||||||

@@ -1,3 +1,303 @@

|

|||||||

# Math 416 Midterm 1 Review

|

# Math 416 Midterm 1 Review

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

So everything we have learned so far is to extend the real line to the complex plane.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

## Chapter 1 Complex Numbers

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### Definition of complex numbers

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

An ordered pair of real numbers $(x, y)$ can be represented as a complex number $z = x + yi$, where $i$ is the imaginary unit.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

With operations defined as:

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

$$

|

||||||

|

(x_1 + y_1i) + (x_2 + y_2i) = (x_1 + x_2) + (y_1 + y_2)i

|

||||||

|

$$

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

$$

|

||||||

|

(x_1 + y_1i) \cdot (x_2 + y_2i) = (x_1x_2 - y_1y_2) + (x_1y_2 + x_2y_1)i

|

||||||

|

$$

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### De Moivre's Formula

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Every complex number $z$ can be written as $z = r(\cos \theta + i \sin \theta)$, where $r$ is the magnitude of $z$ and $\theta$ is the argument of $z$.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

$$

|

||||||

|

z^n = r^n(\cos n\theta + i \sin n\theta)

|

||||||

|

$$

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

The De Moivre's formula is useful for finding the $n$th roots of a complex number.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

$$

|

||||||

|

z^n = r^n(\cos n\theta + i \sin n\theta)

|

||||||

|

$$

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### Roots of complex numbers

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Using De Moivre's formula, we can find the $n$th roots of a complex number.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

If $z=r(\cos \theta + i \sin \theta)$, then the $n$th roots of $z$ are given by:

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

$$

|

||||||

|

z_k = r^{1/n}(\cos \frac{\theta + 2k\pi}{n} + i \sin \frac{\theta + 2k\pi}{n})

|

||||||

|

$$

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

for $k = 0, 1, 2, \ldots, n-1$.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

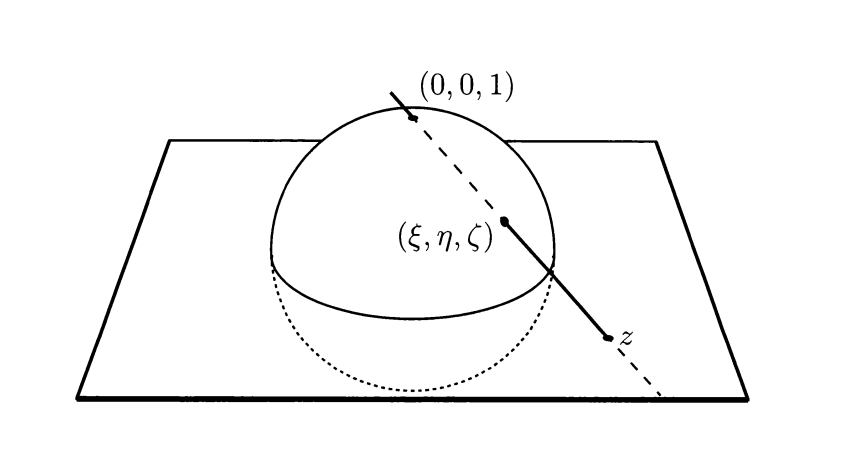

### Stereographic projection

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

The stereographic projection is a map from the unit sphere $S^2$ to the complex plane $\mathbb{C}\setminus\{0\}$.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

The projection is given by:

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

$$

|

||||||

|

z\mapsto \frac{(2Re(z), 2Im(z), |z|^2-1)}{|z|^2+1}

|

||||||

|

$$

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

The inverse map is given by:

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

$$

|

||||||

|

(\xi,\eta, \zeta)\mapsto \frac{\xi + i\eta}{1 - \zeta}

|

||||||

|

$$

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

## Chapter 2 Complex Differentiation

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### Definition of complex differentiation

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Let the complex plane $\mathbb{C}$ be defined in an open subset $G$ of $\mathbb{C}$. (Domain)

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Then $f$ is said to be differentiable at $z_0\in G$ if the limit

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

$$

|

||||||

|

\lim_{z\to z_0} \frac{f(z)-f(z_0)}{z-z_0}

|

||||||

|

$$

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

exists.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

The limit is called the derivative of $f$ at $z_0$ and is denoted by $f'(z_0)$.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

To prove that a function is differentiable, we can use the standard delta-epsilon definition of a limit.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

$$

|

||||||

|

\left|\frac{f(z)-f(z_0)}{z-z_0} - f'(z_0)\right| < \epsilon

|

||||||

|

$$

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

whenever $0 < |z-z_0| < \delta$.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

With such definition, all the properties of real differentiation can be extended to complex differentiation.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

#### Differentiation of complex functions

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

1. If $f$ is differentiable at $z_0$, then $f$ is continuous at $z_0$.

|

||||||

|

2. If $f,g$ are differentiable at $z_0$, then $f+g, fg$ are differentiable at $z_0$.

|

||||||

|

$$

|

||||||

|

(f+g)'(z_0) = f'(z_0) + g'(z_0)

|

||||||

|

$$

|

||||||

|

$$

|

||||||

|

(fg)'(z_0) = f'(z_0)g(z_0) + f(z_0)g'(z_0)

|

||||||

|

$$

|

||||||

|

3. If $f,g$ are differentiable at $z_0$ and $g(z_0)\neq 0$, then $f/g$ is differentiable at $z_0$.

|

||||||

|

$$

|

||||||

|

\left(\frac{f}{g}\right)'(z_0) = \frac{f'(z_0)g(z_0) - f(z_0)g'(z_0)}{g(z_0)^2}

|

||||||

|

$$

|

||||||

|

4. If $f$ is differentiable at $z_0$ and $g$ is differentiable at $f(z_0)$, then $g\circ f$ is differentiable at $z_0$.

|

||||||

|

$$

|

||||||

|

(g\circ f)'(z_0) = g'(f(z_0))f'(z_0)

|

||||||

|

$$

|

||||||

|

5. If $f(z)=\sum_{k=0}^n c_k(z-z_0)^k$, where $c_k\in\mathbb{C}$, then $f$ is differentiable at $z_0$ and $f'(z_0)=\sum_{k=1}^n kc_k(z_0-z_0)^{k-1}$.

|

||||||

|

$$

|

||||||

|

f'(z_0) = c_1 + 2c_2(z_0-z_0) + 3c_3(z_0-z_0)^2 + \cdots + nc_n(z_0-z_0)^{n-1}

|

||||||

|

$$

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### Cauchy-Riemann Equations

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Let the function defined on an open subset $G$ of $\mathbb{C}$ be $f(x,y)=u(x,y)+iv(x,y)$, where $u,v$ are real-valued functions.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Then $f$ is differentiable at $z_0=x_0+y_0i$ if and only if the partial derivatives of $u$ and $v$ exist at $(x_0,y_0)$ and satisfy the Cauchy-Riemann equations:

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

$$

|

||||||

|

\frac{\partial u}{\partial x} = \frac{\partial v}{\partial y}, \quad \frac{\partial u}{\partial y} = -\frac{\partial v}{\partial x}

|

||||||

|

$$

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### Holomorphic functions

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

A function $f$ is said to be holomorphic on an open subset $G$ of $\mathbb{C}$ if $f$ is differentiable at every point of $G$.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

#### Partial differential operators

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

$$

|

||||||

|

\frac{\partial}{\partial z} = \frac{1}{2}\left(\frac{\partial}{\partial x} - i\frac{\partial}{\partial y}\right)

|

||||||

|

$$

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

$$

|

||||||

|

\frac{\partial}{\partial \bar{z}} = \frac{1}{2}\left(\frac{\partial}{\partial x} + i\frac{\partial}{\partial y}\right)

|

||||||

|

$$

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

This gives that

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

$$

|

||||||

|

\frac{\partial f}{\partial z} = \frac{1}{2}\left(\frac{\partial f}{\partial x} - i\frac{\partial f}{\partial y}\right)=\frac{1}{2}\left(\frac{\partial u}{\partial x} +\frac{\partial v}{\partial y}\right) + \frac{i}{2}\left(\frac{\partial v}{\partial x} - \frac{\partial u}{\partial y}\right)

|

||||||

|

$$

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

$$

|

||||||

|

\frac{\partial f}{\partial \bar{z}} = \frac{1}{2}\left(\frac{\partial f}{\partial x} + i\frac{\partial f}{\partial y}\right)=\frac{1}{2}\left(\frac{\partial u}{\partial x} - \frac{\partial v}{\partial y}\right) + \frac{i}{2}\left(\frac{\partial u}{\partial y} + \frac{\partial v}{\partial x}\right)

|

||||||

|

$$

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

If the function $f$ is holomorphic, then by the Cauchy-Riemann equations, we have

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

$$

|

||||||

|

\frac{\partial f}{\partial \bar{z}} = 0

|

||||||

|

$$

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### Conformal mappings

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

A holomorphic function $f$ is said to be conformal if it preserves the angles between the curves. More formally, if $f$ is holomorphic on an open subset $G$ of $\mathbb{C}$ and $z_0\in G$, $\gamma_1, \gamma_2$ are two curves passing through $z_0$ ($\gamma_1(t_1)=\gamma_2(t_2)=z_0$) and intersecting at an angle $\theta$, then

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

$$

|

||||||

|

\arg(f\circ\gamma_1)'(t_1) - \arg(f\circ\gamma_2)'(t_2) = \theta

|

||||||

|

$$

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

In other words, the angle between the curves is preserved.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

An immediate consequence is that

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

$$

|

||||||

|

\arg(f\cdot \gamma_1)'(t_1) =\arg f'(z_0) + \arg \gamma_1'(t_1)\\

|

||||||

|

\arg(f\cdot \gamma_2)'(t_2) =\arg f'(z_0) + \arg \gamma_2'(t_2)

|

||||||

|

$$

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### Harmonic functions

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

A real-valued function $u$ is said to be harmonic if it satisfies the Laplace equation:

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

$$

|

||||||

|

\frac{\partial^2 u}{\partial x^2} + \frac{\partial^2 u}{\partial y^2} = 0

|

||||||

|

$$

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

## Chapter 3 Linear Fractional Transformations

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### Definition of linear fractional transformations

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

A linear fractional transformation is a function of the form

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

$$

|

||||||

|

\phi(z) = \frac{az+b}{cz+d}

|

||||||

|

$$

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

where $a,b,c,d$ are complex numbers and $ad-bc\neq 0$.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### Properties of linear fractional transformations

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

#### Conformality

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

A linear fractional transformation is conformal.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

$$

|

||||||

|

\phi'(z) = \frac{ad-bc}{(cz+d)^2}

|

||||||

|

$$

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

#### Three-fold transitivity

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

If $z_1,z_2,z_3$ are distinct points in the complex plane, then there exists a unique linear fractional transformation $\phi$ such that $\phi(z_1)=\infty$, $\phi(z_2)=0$, $\phi(z_3)=1$.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

The map is given by

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

$$

|

||||||

|

\phi(z) =\begin{cases}

|

||||||

|

\frac{(z-z_2)(z_1-z_3)}{(z-z_1)(z_2-z_3)} & \text{if } z_1,z_2,z_3 \text{ are all finite}\\

|

||||||

|

\frac{z-z_2}{z_3-z_2} & \text{if } z_1=\infty\\

|

||||||

|

\frac{z_3-z_1}{z-z_1} & \text{if } z_2=\infty\\

|

||||||

|

\frac{z-z_2}{z-z_1} & \text{if } z_3=\infty\\

|

||||||

|

\end{cases}

|

||||||

|

$$

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

So if $z_1,z_2,z_3$, $w_1,w_2,w_3$ are distinct points in the complex plane, then there exists a unique linear fractional transformation $\phi$ such that $\phi(z_i)=w_i$ for $i=1,2,3$.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

#### Inversion

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

#### Factorization

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

#### Clircle

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

## Chapter 4 Elementary Functions

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### Exponential function

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### Trigonometric functions

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### Logarithmic function

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### Power function

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### Inverse trigonometric functions

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

## Chapter 5 Power Series

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### Definition of power series

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### Properties of power series

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### Radius/Region of convergence

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### Cauchy-Hadamard Theorem

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### Cauchy Product (of power series)

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

## Chapter 6 Complex Integration

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### Definition of Riemann Integral for complex functions

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

The complex integral of a complex function $\phi$ on the closed subinterval $[a,b]$ of the real line is said to be piecewise continuous if there exists a partition $a=t_0<t_1<\cdots<t_n=b$ such that $\phi$ is continuous on each open interval $(t_{i-1},t_i)$ and has a finite limit at each discontinuity point of the closed interval $[a,b]$.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

If $\phi$ is piecewise continuous on $[a,b]$, then the complex integral of $\phi$ on $[a,b]$ is defined as

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

$$

|

||||||

|

\int_a^b \phi(t) dt = \int_a^b \operatorname{Re}\phi(t) dt + i\int_a^b \operatorname{Im}\phi(t) dt

|

||||||

|

$$

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### Fundamental Theorem of Calculus

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

If $\phi$ is piecewise continuous on $[a,b]$, then

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

$$

|

||||||

|

\int_a^b \phi'(t) dt = \phi(b)-\phi(a)

|

||||||

|

$$

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### Triangle inequality

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

$$

|

||||||

|

\left|\int_a^b \phi(t) dt\right| \leq \int_a^b |\phi(t)| dt

|

||||||

|

$$

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### Integral on curve

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Let $\gamma$ be a piecewise smooth curve in the complex plane.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

The integral of a complex function $f$ on $\gamma$ is defined as

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

$$

|

||||||

|

\int_\gamma f(z) dz = \int_a^b f(\gamma(t))\gamma'(t) dt

|

||||||

|

$$

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### Properties of complex integrals

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

1. Linearity:

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

## Chapter 7 Cauchy's Theorem

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### Cauchy's Theorem

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### Cauchy's Formula for a Circle

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### Cauchy's Product

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|||||||

@@ -99,7 +99,7 @@ $$

|

|||||||

|

|

||||||

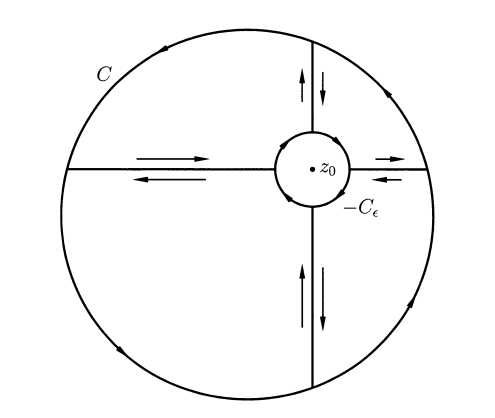

We divide the integral into four parts:

|

We divide the integral into four parts:

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

Notice that $\frac{f(\xi)}{\xi-z}$ is holomorphic whenever $f(\xi)\in U$ and $\xi\in \mathbb{C}\setminus\{z\}$.

|

Notice that $\frac{f(\xi)}{\xi-z}$ is holomorphic whenever $f(\xi)\in U$ and $\xi\in \mathbb{C}\setminus\{z\}$.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|||||||

BIN

public/Math416/Cauchy_theorem_disk.png

Normal file

BIN

public/Math416/Cauchy_theorem_disk.png

Normal file

Binary file not shown.

|

After Width: | Height: | Size: 25 KiB |

BIN

public/Math416/Stereographic_projection.png

Normal file

BIN

public/Math416/Stereographic_projection.png

Normal file

Binary file not shown.

|

After Width: | Height: | Size: 37 KiB |

Reference in New Issue

Block a user