3.6 KiB

Math416 Lecture 11

Continue on integration over complex plane

Continue on last example

Last lecture we have:Let R be a rectangular start from the -a to a, a+ib to -a+ib, \int_{R} e^{-\zeta^2}d\zeta=0, however, the integral consists of four parts:

Path 1: -a\to a

\int_{I_1}e^{-\zeta^2}d\zeta=\int_{-a}^{a}e^{-\zeta^2}d\zeta=\int_{-a}^{a}e^{-x^2}dx

Path 2: a+ib\to -a+ib

\int_{I_2}e^{-\zeta^2}d\zeta=\int_{a+ib}^{-a+ib}e^{-\zeta^2}d\zeta=\int_{0}^{b}e^{-(a+iy)^2}dy

Path 3: -a+ib\to -a-ib

-\int_{I_3}e^{-\zeta^2}d\zeta=-\int_{-a+ib}^{-a-ib}e^{-\zeta^2}d\zeta=-\int_{a}^{-a}e^{-(x-ib)^2}dx

Path 4: -a-ib\to a-ib

-\int_{I_4}e^{-\zeta^2}d\zeta=-\int_{-a-ib}^{a-ib}e^{-\zeta^2}d\zeta=-\int_{b}^{0}e^{-(-a+iy)^2}dy

The reverse of a curve 6.9

If

\gamma:[a,b]\to\mathbb{C}is a curve, then the rever of\gammais the curve-\gamma:[-b,-a]\to\mathbb{C}defined by(-\gamma)(t)=\gamma(a+b-t). It is the curve one obtains from\gammaby traversing it in the opposite direction.

- If

\gammais piecewise inC^1, then-\gammais piecewise inC^1.\int_{-\gamma}f(z)dz=-\int_{\gamma}f(z)dzfor any functionfthat is continuous on\gamma([a,b]).

If we keep b fixed, and let a\to\infty, then

Definition 6.10 (Estimate of the integral)

Let

\gamma:[a,b]\to\mathbb{C}be a piecewiseC^1curve, and letf:[a,b]\to\mathbb{C}be a continuous complex-valued function. LetMbe the maximum of|f|on\gamma([a,b]). (M=\max\{|f(t)|:t\in[a,b]\})Then

\left|\int_{\gamma}f(\zeta)d\zeta\right|\leq L(\gamma)M

Continue on previous example, we have:

\left|\int_{\gamma}f(\zeta)d\zeta\right|\leq L(\gamma)\max_{\zeta\in\gamma}|f(\zeta)|\to 0

Since,

\int_{-\infty}^{\infty}e^{-x^2}dx-\int_{-\infty}^{\infty}e^{-x^2+b^2}(\cos 2bx+i\sin 2bx)dx=0

Since \sin 2bx is odd, and \cos 2bx is even, we have

\int_{-\infty}^{\infty}e^{-x^2}dx=\int_{-\infty}^{\infty}e^{-x^2+b^2}\cos 2bxdx=\sqrt{\pi}e^{-b^2}

Proof for the last step:

\int_{-\infty}^{\infty}e^{-x^2}dx=\sqrt{\pi}

Proof:

Let J=\int_{-\infty}^{\infty}e^{-x^2}dx

Then

J^2=\int_{-\infty}^{\infty}e^{-x^2}dx\int_{-\infty}^{\infty}e^{-y^2}dy=\int_{-\infty}^{\infty}\int_{-\infty}^{\infty}e^{-(x^2+y^2)}dxdy

We can evaluate the integral on the right-hand side by converting to polar coordinates. x=r\cos\theta, y=r\sin\theta,dxdy=rdrd\theta

J^2=\int_{-\infty}^{\infty}\int_{-\infty}^{\infty}e^{-(x^2+y^2)}dxdy=\int_{0}^{2\pi}\int_{0}^{\infty}e^{-r^2}rdrd\theta

J^2=\int_{0}^{2\pi}\int_{0}^{\infty}e^{-r^2}rdrd\theta=\int_{0}^{2\pi}\left[-\frac{1}{2}e^{-r^2}\right]_{0}^{\infty}d\theta

J^2=\int_{0}^{2\pi}\frac{1}{2}d\theta=\pi

J=\sqrt{\pi}

EOP

Chapter 7 Cauchy's theorem

Cauchy's theorem (Fundamental theorem of complex function theory)

Let \gamma be a closed curve in \mathbb{C} and let u be an open set containing $\gamma^*$. Let f be a holomorphic function on u. Then

\int_{\gamma}f(z)dz=0

Note: What "containing $\gamma^*$" means? (Rabbit hole for topologists)

Lemma 7.1 (Goursat's lemma)

Cauchy's theorem is true if \gamma is a triangle.

Proof:

We plan to keep shrinking the triangle until f(\zeta+h)=f(\zeta)+hf'(\zeta)+\mu(h) where \mu(h) is a function of h that goes to 0 as h\to 0.

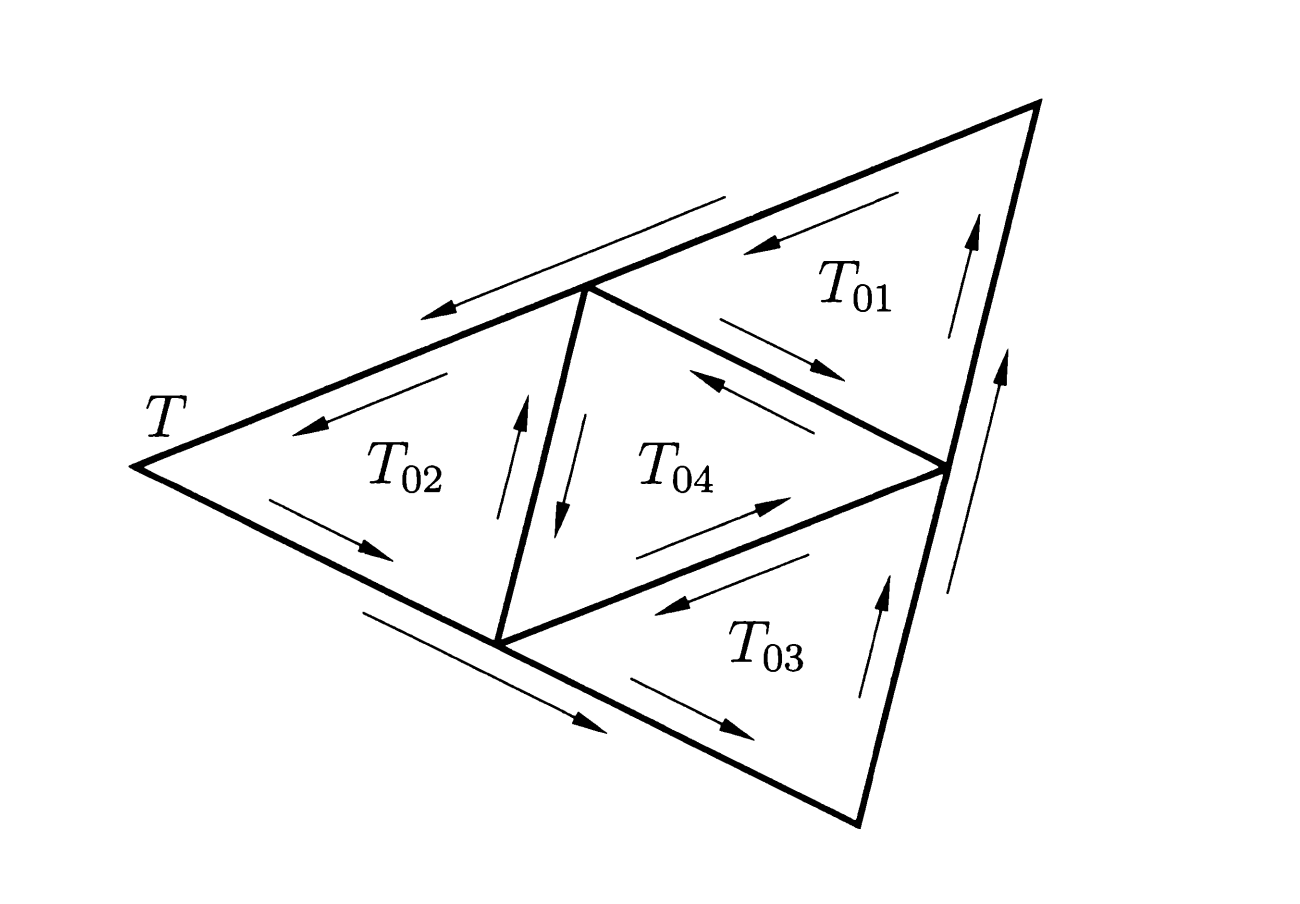

Let's start with a triangle T with vertices z_1,z_2,z_3.

We divide T into four smaller triangles by drawing lines from the midpoints of the sides to the opposite vertices.