12 KiB

Math401 Topic 3: Separable Hilbert spaces

Infinite-dimensional Hilbert spaces

Recall from Topic 1.

Let \lambda be a measure on \mathbb{R}, or any other field you are interested in.

A function is square integrable if

\int_\mathbb{R} |f(x)|^2 d\lambda(x)<\infty

L^2 space and general Hilbert spaces

Definition of L^2(\mathbb{R},\lambda)

The space L^2(\mathbb{R},\lambda) is the space of all square integrable, measurable functions on \mathbb{R} with respect to the measure \lambda (The Lebesgue measure).

The Hermitian inner product is defined by

\langle f,g\rangle=\int_\mathbb{R} \overline{f(x)}g(x) d\lambda(x)

The norm is defined by

\|f\|=\sqrt{\int_\mathbb{R} |f(x)|^2 d\lambda(x)}

The space L^2(\mathbb{R},\lambda) is complete.

[Proof ignored here]

Recall the definition of complete metric space.

The inner product space L^2(\mathbb{R},\lambda) is complete.

Note that by some general result in point-set topology, a normed vector space can always be enlarged so as to become complete. This process is called completion of the normed space.

Some exercise is showing some hints for this result:

Show that the subspace of

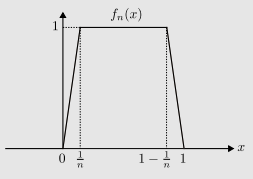

L^2(\mathbb{R},\lambda)consisting of square integrable continuous functions is not closed.Suggestion: consider the sequence of continuous functions

f_1(x), f_2(x),\cdots, wheref_n(x)is defined by the following graph:Show that

f_nconverges in theL^2norm to a functionf\in L^2(\mathbb{R},\lambda)but the limit functionfis not continuous. Draw the graph off_nto make this clear.

Definition of general Hilbert space

A Hilbert space is a complete inner product vector space.

General Pythagorean theorem

Let u_1,u_2,\cdots,u_N be an orthonormal set in an inner product space \mathscr{V} (may not be complete). Then for all v\in \mathscr{V},

\|v\|^2=\sum_{i=1}^N |\langle v,u_i\rangle|^2+\left\|v-\sum_{i=1}^N \langle v,u_i\rangle u_i\right\|^2

[Proof ignored here]

Bessel's inequality

Let u_1,u_2,\cdots,u_N be an orthonormal set in an inner product space \mathscr{V} (may not be complete). Then for all v\in \mathscr{V},

\sum_{i=1}^N |\langle v,u_i\rangle|^2\leq \|v\|^2

Immediate from the general Pythagorean theorem.

Orthonormal bases

An orthonormal subset S of a Hilbert space \mathscr{H} is a set all of whose elements have norm 1 and are mutually orthogonal. (\forall u,v\in S, \langle u,v\rangle=0)

Definition of orthonormal basis

An orthonormal subset of S of a Hilbert space \mathscr{H} is an orthonormal basis of \mathscr{H} if there are no other orthonormal subsets of \mathscr{H} that contain S as a proper subset.

Theorem of existence of orthonormal basis

Every separable Hilbert space has an orthonormal basis.

[Proof ignored here]

Theorem of Fourier series

Let \mathscr{H} be a separable Hilbert space with an orthonormal basis \{e_n\}. Then for any f\in \mathscr{H},

f=\sum_{n=1}^\infty \langle f,e_n\rangle e_n

The series converges to some g\in \mathscr{H}.

[Proof ignored here]

Fourier series in L^2([0,2\pi],\lambda)

Let f\in L^2([0,2\pi],\lambda).

f_N(x)=\sum_{n:|n|\leq N} c_n\frac{e^{inx}}{\sqrt{2\pi}}

where c_n=\frac{1}{2\pi}\int_0^{2\pi} f(x)e^{-inx} dx.

The series converges to some f\in L^2([0,2\pi],\lambda) as N\to \infty.

This is the Fourier series of f.

Hermite polynomials

The subspace spanned by polynomials is dense in L^2(\mathbb{R},\lambda).

An orthonormal basis of L^2(\mathbb{R},\lambda) can be obtained by the Gram-Schmidt process on \{1,x,x^2,\cdots\}.

The polynomials are called the Hermite polynomials.

Isomorphism and \ell_2 space

Definition of isomorphic Hilbert spaces

Let \mathscr{H}_1 and \mathscr{H}_2 be two Hilbert spaces.

\mathscr{H}_1 and \mathscr{H}_2 are isomorphic if there exists a surjective linear map U:\mathscr{H}_1\to \mathscr{H}_2 that is bijective and preserves the inner product.

\langle Uf,Ug\rangle=\langle f,g\rangle

for all f,g\in \mathscr{H}_1.

When \mathscr{H}_1=\mathscr{H}_2, the map U is called unitary.

\ell_2 space

The space \ell_2 is the space of all square summable sequences.

\ell_2=\left\{(a_n)_{n=1}^\infty: \sum_{n=1}^\infty |a_n|^2<\infty\right\}

An example of element in \ell_2 is (1,0,0,\cdots).

With inner product

\langle (a_n)_{n=1}^\infty, (b_n)_{n=1}^\infty\rangle=\sum_{n=1}^\infty \overline{a_n}b_n

It is a Hilbert space (every Cauchy sequence in \ell_2 converges to some element in \ell_2).

Bounded operators and continuity

Let T:\mathscr{V}\to \mathscr{W} be a linear map between two vector spaces \mathscr{V} and \mathscr{W}.

We define the norm of \|\cdot\| on \mathscr{V} and \mathscr{W}.

Then T is continuous if for all u\in \mathscr{V}, if u_n\to u in \mathscr{V}, then T(u_n)\to T(u) in \mathscr{W}.

Using the delta-epsilon language, we can say that T is continuous if for all \epsilon>0, there exists a \delta>0 such that if \|u-v\|<\delta, then \|T(u)-T(v)\|<\epsilon.

Definition of bounded operator

A linear map T:\mathscr{V}\to \mathscr{W} is bounded if

\|T\|=\sup_{\|u\|=1}\|T(u)\|< \infty

Theorem of continuity and boundedness

A linear map T:\mathscr{V}\to \mathscr{W} is continuous if and only if it is bounded.

[Proof ignored here]

Definition of bounded Hilbert space

The set of all bounded linear operators in \mathscr{V} is denoted by \mathscr{B}(\mathscr{V}).

Direct sum of Hilbert spaces

Suppose \mathscr{H}_1 and \mathscr{H}_2 are two Hilbert spaces.

The direct sum of \mathscr{H}_1 and \mathscr{H}_2 is the Hilbert space \mathscr{H}_1\oplus \mathscr{H}_2 with the inner product

\langle (u_1,u_2),(v_1,v_2)\rangle=\langle u_1,v_1\rangle_{\mathscr{H}_1}+\langle u_2,v_2\rangle_{\mathscr{H}_2}

Such space is denoted by \mathscr{H}_1\oplus \mathscr{H}_2.

A countable direct sum of Hilbert spaces can be defined similarly, as long as it is bounded.

That is, \{u_n:n=1,2,\cdots\} is a sequence of elements in \mathscr{H}_n, and \sum_{n=1}^\infty \|u_n\|^2<\infty.

The inner product in such countable direct sum is defined by

\langle (u_n)_{n=1}^\infty, (v_n)_{n=1}^\infty\rangle=\sum_{n=1}^\infty \langle u_n,v_n\rangle_{\mathscr{H}_n}

Such space is denoted by \mathscr{H}=\bigoplus_{n=1}^\infty \mathscr{H}_n.

Closed subspaces of Hilbert spaces

Definition of closed subspace

A subspace \mathscr{M} of a Hilbert space \mathscr{H} is closed if every convergent sequence in \mathscr{M} converges to some element in \mathscr{M}.

Definition of pairwise orthogonal subspaces

Two subspaces \mathscr{M}_1 and \mathscr{M}_2 of a Hilbert space \mathscr{H} are pairwise orthogonal if \langle u,v\rangle=0 for all u\in \mathscr{M}_1 and v\in \mathscr{M}_2.

Orthogonal projections

Definition of orthogonal complement

The orthogonal complement of a subspace \mathscr{M} of a Hilbert space \mathscr{H} is the set of all elements in \mathscr{H} that are orthogonal to every element in \mathscr{M}.

It is denoted by \mathscr{M}^\perp=\{u\in \mathscr{H}: \langle u,v\rangle=0,\forall v\in \mathscr{M}\}.

Projection theorem

Let \mathscr{H} be a Hilbert space and \mathscr{M} be a closed subspace of \mathscr{H}. Then for any v\in \mathscr{H} can be uniquely decomposed as v=u+w where u\in \mathscr{M} and w\in \mathscr{M}^\perp.

[Proof ignored here]

Dual Hilbert spaces

Norm of linear functionals

Let \mathscr{H} be a Hilbert space.

The norm of a linear functional f\in \mathscr{H}^* is defined by

\|f\|=\sup_{\|u\|=1}|f(u)|

Definition of dual Hilbert space

The dual Hilbert space of \mathscr{H} is the space of all bounded linear functionals on \mathscr{H}.

It is denoted by \mathscr{H}^*.

\mathscr{H}^*=\mathscr{B}(\mathscr{H},\mathbb{C})=\{f: \mathscr{H}\to \mathbb{C}: f\text{ is linear and }\|f\|<\infty\}

You can exchange the \mathbb{C} with any other field you are interested in.

The Riesz lemma

For each f\in \mathscr{H}^*, there exists a unique v_f\in \mathscr{H} such that f(u)=\langle u,v_f\rangle for all u\in \mathscr{H}. And \|f\|=\|v_f\|.

[Proof ignored here]

Definition of bounded sesqilinear form

A bounded sesqilinear form on \mathscr{H} is a function B: \mathscr{H}\times \mathscr{H}\to \mathbb{C} satisfying

B(u,av+bw)=aB(u,v)+bB(u,w)for allu,v,w\in \mathscr{H}anda,b\in \mathbb{C}.B(av+bw,u)=\overline{a}B(v,u)+\overline{b}B(w,u)for allu,v,w\in \mathscr{H}anda,b\in \mathbb{C}.|B(u,v)|\leq C\|u\|\|v\|for allu,v\in \mathscr{H}and some constantC>0.

There exists a unique bounded linear operator A\in \mathscr{B}(\mathscr{H}) such that B(u,v)=\langle Au,v\rangle for all u,v\in \mathscr{H}. The norm of A is the smallest constant C such that |B(u,v)|\leq C\|u\|\|v\| for all u,v\in \mathscr{H}.

[Proof ignored here]

The adjoint of a bounded operator

Let A\in \mathscr{B}(\mathscr{H}). And bounded sesqilinear form B: \mathscr{H}\times \mathscr{H}\to \mathbb{C} such that B(u,v)=\langle u,Av\rangle for all u,v\in \mathscr{H}. Then there exists a unique bounded linear operator A^*\in \mathscr{B}(\mathscr{H}) such that B(u,v)=\langle A^*u,v\rangle for all u,v\in \mathscr{H}.

[Proof ignored here]

And \|A^*\|=\|A\|.

Additional properties of bounded operators:

Let A,B\in \mathscr{B}(\mathscr{H}) and a,b\in \mathbb{C}. Then

(aA+bB)^*=\overline{a}A^*+\overline{b}B^*.(AB)^*=B^*A^*.(A^*)^*=A.\|A^*\|=\|A\|.\|A^*A\|=\|A\|^2.

Definition of self-adjoint operator

An operator A\in \mathscr{B}(\mathscr{H}) is self-adjoint if A^*=A.

Definition of normal operator

An operator N\in \mathscr{B}(\mathscr{H}) is normal if NN^*=N^*N.

Definition of unitary operator

An operator U\in \mathscr{B}(\mathscr{H}) is unitary if U^*U=UU^*=I.

where I is the identity operator on \mathscr{H}.

Definition of orthogonal projection

An operator P\in \mathscr{B}(\mathscr{H}) is an orthogonal projection if P^*=P and P^2=P.

Tensor product of (infinite-dimensional) Hilbert spaces

Definition of tensor product

Let \mathscr{H}_1 and \mathscr{H}_2 be two Hilbert spaces. u_1\in \mathscr{H}_1 and u_2\in \mathscr{H}_2. Then u_1\otimes u_2 is an conjugate bilinear functional on \mathscr{H}_1\times \mathscr{H}_2.

(u_1\otimes u_2)(v_1,v_2)=\langle u_1,v_1\rangle_{\mathscr{H}_1}\langle u_2,v_2\rangle_{\mathscr{H}_2}

Let \mathscr{V} be the set of all finite lienar combination of such conjugate bilinear functionals. We define the inner product on \mathscr{V} by

\langle u\otimes v,u'\otimes v'\rangle=\langle u,u'\rangle_{\mathscr{H}_1}\langle v,v'\rangle_{\mathscr{H}_2}

The infinite-dimensional tensor product of \mathscr{H}_1 and \mathscr{H}_2 is the completion (extension of those bilinear functionals to make the set closed) of \mathscr{V} with respect to the norm induced by the inner product.

Denoted by \mathscr{H}_1\otimes \mathscr{H}_2.

The orthonormal basis of \mathscr{H}_1\otimes \mathscr{H}_2 is \{u_i\otimes v_j:i=1,2,\cdots,j=1,2,\cdots\}. where u_i is the orthonormal basis of \mathscr{H}_1 and v_j is the orthonormal basis of \mathscr{H}_2.

Fock space

Definition of Fock space

Let \mathscr{H}^{\otimes n} be the $n$-fold tensor product of \mathscr{H}.

Set \mathscr{H}^{\otimes 0}=\mathbb{C}.

The Fock space of \mathscr{H} is the direct sum of all \mathscr{H}^{\otimes n}.

\mathscr{F}(\mathscr{H})=\bigoplus_{n=0}^\infty \mathscr{H}^{\otimes n}

For example, if \mathscr{H}=L^2(\mathbb{R},\lambda), then an element in \mathscr{F}(\mathscr{H}) is a sequence of functions \psi=(\psi_0,\psi_1(x_1),\psi_2(x_1,x_2),\cdots) such that |\psi_0|^2+\sum_{n=1}^\infty \int|\psi_n(x_1,\cdots,x_n)|^2dx_1\cdots dx_n<\infty.