21 KiB

Math401 Topic 4: The quantum version of probabilistic concepts

In mathematics, on often speaks of non-commutative instead of quantum constructions.

Note, in this section, we will see a lot of mixed used terms used in physics and mathematics. I will use italic to denote the terminology used in physics. It is safe to ignore them if you just care about the mathematics.

Section 1: Generalities about classical versus quantum systems

In classical physics, we assume that a system's properties have well-defined values regardless of how we choose to measure them.

Basic terminology

Set of states

The preparation of a system builds a convex set of states as our initial condition for the system.

For a collection of N system. Let procedure N_1=\lambda P_1 be a preparation procedure for state P_1, and N_2=(1-\lambda) P_2 be a preparation procedure for state P_2. The state of the collection is N=\lambda N_1+(1-\lambda) N_2.

Set of effects

The set of effects is the set of all possible outcomes of a measurement. \Omega=\{\omega_1, \omega_2, \ldots, \omega_n\}. Where each \omega_i is an associated effect, or some query problems regarding the system. (For example, is outcome \omega_i observed?)

Registration of outcomes

A pair of state and effect determines a probability E_i(P)=p(\omega_i|P). By the law of large numbers, this probability shall converge to N(\omega_i)/N as N increases.

Quantum states, observables (random variables), and effects can be represented mathematically by linear operators on a Hilbert space.

Section 2: Examples of physical experiment in language of mathematics

Sten-Gernach experiment

State preparation: Silver tams are emitted from a thermal source and collimated to form a beam.

Measurement: Silver atoms interact with the field produced by the magnet and impinges on the class plate.

Registration: The impression left on the glass pace by the condensed silver atoms.

Section 3: Finite probability spaces in the language of Hilbert space and operators

Superposition is a linear combination of two or more states.

A quantum coin can be represented mathematically by linear combination of |0\rangle and |1\rangle.$\alpha|0\rangle+\beta|1\rangle\in\mathscr{H}\cong\mathbb{C}^2$.

For the rest of the material, we shall take the

\mathscr{H}to be vector space over\mathbb{C}.

Definitions in classical probability under generalized probability theory

Definition of states (classical probability)

A state in classical probability is a probability distribution on the set of all possible outcomes. We can list as (p_1,p_2,\cdots,p_n).

To each event A\in \Omega, we associate the operator on \mathscr{H} of multiplication by the indicator function P_A\coloneqq M_{\mathbb{I}_A}:f\mapsto \mathbb{I}_A f that projects onto the subspace of \mathscr{H} corresponding to the event A.

P_A=\sum_{k=1}^n a_k|k\rangle\langle k|

where a_k\in\{0,1\}, and a_k=1 if and only if k\in A. Note that P_A^*=P_A and P_A^2=P_A.

Definition of density operator (classical probability)

Let (p_1,p_2,\cdots,p_n) be a probability distribution on X, where p_k\geq 0 and \sum_{k=1}^n p_k=1. The density operator \rho is defined by

\rho=\sum_{k=1}^n p_k|k\rangle\langle k|

The probability of event A relative to the probability distribution (p_1,p_2,\cdots,p_n) becomes the trace of the product of \rho and P_A.

\operatorname{Prob}_\rho(A)\coloneqq\text{Tr}(\rho P_A)

Definition of random variables (classical probability)

A random variable is a function f:X\to\mathbb{R}. It can also be written in operator form:

F=\sum_{k=1}^n f(k)P_{\{k\}}

The expectation of f relative to the probability distribution (p_1,p_2,\cdots,p_n) is given by

\mathbb{E}_\rho(f)=\sum_{k=1}^n p_k f(k)=\operatorname{Tr}(\rho F)

Note, by our definition of the operator F,P_A,\rho (all diagonal operators) commute among themselves, which does not hold in general, in non-commutative (quantum) theory.

Section 4: Why we need generalized probability theory to study quantum systems

Story of light polarization and violation of Bell's inequality.

Classical picture of light polarization and Bell's inequality

An interesting story will be presented here.

Polarization of light

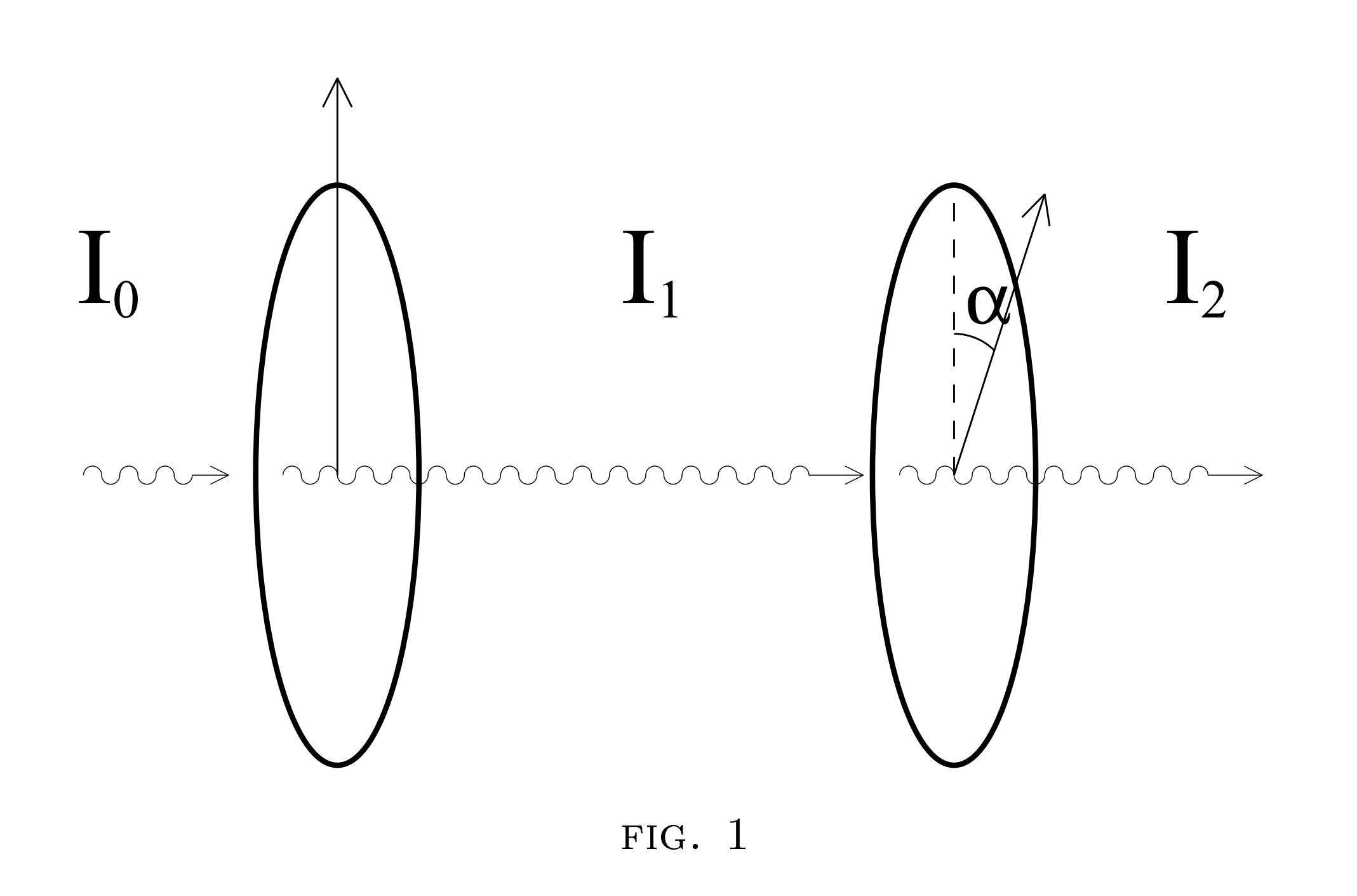

The light which comes through a polarizer is polarized in a certain direction. If we fixed the first filter and rotate the second filter, we will observe the intensity of the light will change.

The light intensity decreased with \alpha (the angle between the two filters). The light should vanished when \alpha=\pi/2.

By experimental measurement, the intensity of the light passing the first filter is half the beam intensity (Assume the original beam is completely unpolarized).

Then I_1=I_0/2, and

I_2=I_0\cos^2\alpha

Claim: there exist a smallest package of monochromatic light, which is a photon.

We can model the behavior of each individual photon passing through the filter with direction \alpha with random variable P_\alpha. The P_\alpha(\omega)=1 if the photon passes through the filter, and P_\alpha(\omega)=0 if the photon does not pass through the filter.

Then, the probability of the photon passing through the two filters with direction \alpha and \beta is given by

\mathbb{E}(P_\alpha P_\beta)=\operatorname{Prob}(P_\alpha=1 \text{ and } P_\beta=1)=\frac{1}{2}\cos^2(\alpha-\beta)

However, for system of 3 polarizing filters F_1,F_2,F_3, having direction \alpha_1,\alpha_2,\alpha_3. If we put them on the optical bench in pairs, Then we will have three random variables P_1,P_2,P_3.

Bell's 3 variable inequality

\operatorname{Prob}(P_1=1,P_3=0)\leq \operatorname{Prob}(P_1=1,P_2=0)+\operatorname{Prob}(P_2=1,P_3=0)

Proof

By the law of total probability, (The event that the photon passes through the first filter but not the third filter is the union of the event that the photon did not pass through the second filter and the event that the photon passed the second filter and did not pass through the third filter) we have

\begin{aligned}

\operatorname{Prob}(P_1=1,P_3=0)&=\operatorname{Prob}(P_1=1,P_2=0,P_3=0)+\operatorname{Prob}(P_1=1,P_2=1,P_3=0)\\

&=\operatorname{Prob}(P_1=1,P_2=0)\operatorname{Prob}(P_3=0)+\operatorname{Prob}(P_2=1,P_3=0)\operatorname{Prob}(P_1=1)\\

&\leq\operatorname{Prob}(P_1=1,P_2=0)+\operatorname{Prob}(P_2=1,P_3=0)

\end{aligned}

However, according to our experimental measurement, for any pair of polarizers F_i,F_j, by the complement rule, we have

\begin{aligned}

\operatorname{Prob}(P_i=1,P_j=0)&=\operatorname{Prob}(P_i=1)-\operatorname{Prob}(P_i=1,P_j=1)\\

&=\frac{1}{2}-\frac{1}{2}\cos^2(\alpha_i-\alpha_j)\\

&=\frac{1}{2}\sin^2(\alpha_i-\alpha_j)

\end{aligned}

This leads to a contradiction if we apply the inequality to the experimental data.

\frac{1}{2}\sin^2(\alpha_1-\alpha_3)\leq\frac{1}{2}\sin^2(\alpha_1-\alpha_2)+\frac{1}{2}\sin^2(\alpha_2-\alpha_3)

If \alpha_1=0,\alpha_2=\frac{\pi}{6},\alpha_3=\frac{\pi}{3}, then

\begin{aligned}

\frac{1}{2}\sin^2(-\frac{\pi}{3})&\leq\frac{1}{2}\sin^2(-\frac{\pi}{6})+\frac{1}{2}\sin^2(\frac{\pi}{6}-\frac{\pi}{3})\\

\frac{3}{8}&\leq\frac{1}{8}+\frac{1}{8}\\

\frac{3}{8}&\leq\frac{1}{4}

\end{aligned}

This is a contradiction, so Bell's inequality is violated.

QED

Other revised experiments (eg. Aspect's experiment, Calcium entangled photon experiment) are also conducted and the inequality is still violated.

The true model of light polarization

The full description of the light polarization is given belows:

State of polarization of a photon: \psi=\alpha|0\rangle+\beta|1\rangle, where |0\rangle and |1\rangle are the two orthogonal polarization states in \mathbb{C}^2.

Polarization filter (generalized 0,1 valued random variable): orthogonal projection P_\alpha on \mathbb{C}^2 corresponding to the direction \alpha. (operator satisfies P_\alpha^*=P_\alpha=P_\alpha^2.)

The matrix representation of P_\alpha is given by

P_\alpha=\begin{pmatrix}

\cos^2(\alpha) & \cos(\alpha)\sin(\alpha)\\

\cos(\alpha)\sin(\alpha) & \sin^2(\alpha)

\end{pmatrix}

Probability of a photon passing through the filter P_\alpha is given by \langle P_\alpha\psi,\psi\rangle, this is \cos^2(\alpha) if we set \psi=|0\rangle.

Since the probability of a photon passing through the three filters is not commutative, it is impossible to discuss \operatorname{Prob}(P_1=1,P_3=0) in the classical setting.

Section 5: The non-commutative (quantum) probability theory

Let \mathscr{H} be a Hilbert space. \mathscr{H} consists of complex-valued functions on a finite set \Omega=\{1,2,\cdots,n\}. and that the functions (e_1,e_2,\cdots,e_n) form an orthonormal basis of \mathscr{H}. We use Dirac notation |k\rangle to denote the basis vector e_k.

In classical settings, multiplication operators is now be the full space of bounded linear operators on \mathscr{H}. (Denoted by \mathscr{B}(\mathscr{H}))

Let A,B\in\mathscr{F} be the set of all events in the classical probability settings. X denotes the set of all possible outcomes.

A orthogonal projection on a Hilbert space is a projection operator satisfying

P^*=PandP^2=P. We denote the set of all orthogonal projections on\mathscr{H}by\mathscr{P}.This can be found in linear algebra. Orthogonal projection

Let P,Q\in\mathscr{P} be the event in non-commutative (quantum) probability space. R(\cdot) is the range of the operator. P^\perp is the orthogonal complement of P.

| Classical | Classical interpretation | Non-commutative (Quantum) | Non-commutative (Quantum) interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

A\subset B |

Event A is a subset of event B |

P\leq Q |

R(P)\subseteq R(Q) Range of event P is a subset of range of event Q |

A\cap B |

Both event A and B happened |

P\land Q |

projection to R(P)\cap R(Q) Range of event P and event Q happened |

A\cup B |

Any of the event A or B happened |

P\lor Q |

projection to R(P)\cup R(Q) Range of event P or event Q happened |

X\subset A or A^c |

Event A did not happen |

P^\perp |

projection$R(P)^\perp$ Range of event P is the orthogonal complement of range of event P |

In such setting, some rules of classical probability theory are not valid in quantum probability theory.

In classical probability theory, A\cap(B\cup C)=(A\cap B)\cup(A\cap C).

In quantum probability theory, P\land(Q\lor R)\neq(P\land Q)\lor(P\land R) in general.

Definitions of non-commutative (quantum) probability theory under generalized probability theory

Definition of states (non-commutative (quantum) probability theory)

A state on (\mathscr{B}(\mathscr{H}),\mathscr{P}) is a map \mu:\mathscr{P}\to[0,1] such that:

\mu(O)=0, whereOis the zero projection.- If

P_1,P_2,\cdots,P_nare pairwise disjoint orthogonal projections, then\mu(P_1\lor P_2\lor\cdots\lor P_n)=\sum_{i=1}^n\mu(P_i).

Where projections are disjoint if P_iP_j=P_jP_i=O.

Definition of density operator (non-commutative (quantum) probability theory)

A density operator \rho on the finite-dimensional Hilbert space \mathscr{H} is:

- self-adjoint (

A^*=A, that is\langle Ax,y\rangle=\langle x,Ay\ranglefor allx,y\in\mathscr{H}) - positive semi-definite (all eigenvalues are non-negative)

\operatorname{Tr}(\rho)=1.

If (|\psi_1\rangle,|\psi_2\rangle,\cdots,|\psi_n\rangle) is an orthonormal basis of \mathscr{H} consisting of eigenvectors of \rho, for the eigenvalue p_1,p_2,\cdots,p_n, then p_j\geq 0 and \sum_{j=1}^n p_j=1.

We can write \rho as

\rho=\sum_{j=1}^n p_j|\psi_j\rangle\langle\psi_j|

(under basis |\psi_j\rangle, it is a diagonal matrix with p_j on the diagonal)

Every basis of \mathscr{H} can be decomposed to these forms.

Theorem: Born's rule

Let \rho be a density operator on \mathscr{H}. then

\mu(P)\coloneqq\operatorname{Tr}(\rho P)=\sum_{j=1}^n p_j\langle\psi_j|P|\psi_j\rangle

Defines a probability measure on the space \mathscr{P}.

[Proof ignored here]

Theorem: Gleason's theorem (very important)

Let \mathscr{H} be a Hilbert space over \mathbb{C} or \mathbb{R} of dimension n\geq 3. Let \mu be a state on the space \mathscr{P} of projections on \mathscr{H}. Then there exists a unique density operator \rho such that

\mu(P)=\operatorname{Tr}(\rho P)

for all P\in\mathscr{P}. \mathscr{P} is the space of all orthogonal projections on \mathscr{H}.

[Proof ignored here]

Definition of random variable or Observables (non-commutative (quantum) probability theory)

It is the physical measurement of a system that we are interested in. (kinetic energy, position, momentum, etc.)

\mathscr{B}(\mathbb{R}) is the set of all Borel sets on \mathbb{R}.

An random variable on the Hilbert space \mathscr{H} is a projection valued map P:\mathscr{B}(\mathbb{R})\to\mathscr{P}.

With the following properties:

P(\emptyset)=O(the zero projection)P(\mathbb{R})=I(the identity projection)- For any sequence

A_1,A_2,\cdots,A_n\in \mathscr{B}(\mathbb{R}). the following holds:

(a)P(\bigcup_{i=1}^n A_i)=\bigvee_{i=1}^n P(A_i)

(b)P(\bigcap_{i=1}^n A_i)=\bigwedge_{i=1}^n P(A_i)

(c)P(A^c)=I-P(A)(d) IfA_jare mutually disjoint (that isP(A_i)P(A_j)=P(A_j)P(A_i)=Ofori\neq j), thenP(\bigcup_{j=1}^n A_j)=\sum_{j=1}^n P(A_j)

Definition of probability of a random variable

For a system prepared in state \rho, the probability of the random variable by the projection-valued measure P is in the Borel set A is \operatorname{Tr}(\rho P(A)).

Expectation of an random variable and projective measurement

Notice that if we set \lambda is observed with probability p_\lambda=\operatorname{Tr}(\rho P_\lambda). \rho'\coloneqq\sum_{\lambda\in sp(T)}P_\lambda \rho P_\lambda is a density operator.

Definition of expectation of operators

Let T be a self-adjoint operator on \mathscr{H}. The expectation of T relative to the density operator \rho is given by

\mathbb{E}_\rho(T)=\operatorname{Tr}(\rho T)=\sum_{\lambda\in sp(T)}\lambda \operatorname{Tr}(\rho P(\lambda))

if we set T=\sum_{\lambda\in sp(T)}\lambda P_\lambda, then \mathbb{E}_\rho(T)=\sum_{\lambda\in sp(T)}\lambda \operatorname{Tr}(\rho P(\lambda)).

The uncertainty principle

Let A,B be two self-adjoint operators on \mathscr{H}. Then we define the following two self-adjoint operators:

i[A,B]\coloneqq i(AB-BA)

A\circ B\coloneqq \frac{AB+BA}{2}

Note that A\circ B satisfies Jordan's identity.

(A\circ B)\circ (A\circ A)=A\circ (B\circ (A\circ A))

Definition of variance

Given a state \rho, the variance of A is given by

\operatorname{Var}_\rho(A)\coloneqq\mathbb{E}_\rho(A^2)-\mathbb{E}_\rho(A)^2=\operatorname{Tr}(\rho A^2)-\operatorname{Tr}(\rho A)^2

Definition of covariance

Given a state \rho, the covariance of A and B is given by the Jordan product of A and B.

\operatorname{Cov}_\rho(A,B)\coloneqq\mathbb{E}_\rho(A\circ B)-\mathbb{E}_\rho(A)\mathbb{E}_\rho(B)=\operatorname{Tr}(\rho A\circ B)-\operatorname{Tr}(\rho A)\operatorname{Tr}(\rho B)

Robertson-Schrödinger uncertainty relation in finite dimensional Hilbert space

Let \rho be a state on \mathscr{H}, A,B be two self-adjoint operators on \mathscr{H}. Then

\operatorname{Var}_\rho(A)\operatorname{Var}_\rho(B)\geq\operatorname{Cov}_\rho(A,B)^2+\frac{1}{4}|\mathbb{E}_\rho([A,B])|^2

If \rho is a pure state (\rho=|\psi\rangle\langle\psi| for some unit vector |\psi\rangle\in\mathscr{H}), and the equality holds, then A and B are collinear (i.e. A=c B for some constant c\in\mathbb{R}).

When A and B commute, the classical inequality is recovered (Cauchy-Schwarz inequality).

\operatorname{Var}_\rho(A)\operatorname{Var}_\rho(B)\geq\operatorname{Cov}_\rho(A,B)^2

[Proof ignored here]

The uncertainty relation for unbounded symmetric operators

Definition of symmetric operator

An operator A is symmetric if for all \phi,\psi\in\mathscr{H}, we have

\langle A\phi,\psi\rangle=\langle\phi,A\psi\rangle

An example of symmetric operator is T(\psi)=i\hbar\frac{d\psi}{dx}. If we let \mathscr{H}=\mathscr{D}(T), \hbar is the Planck constant.

\mathscr{D}(T) be the space of all square integrable, differentiable, and it's derivative is also square integrable functions on \mathbb{R}.

Definition of joint domain of two operators

Let (A,\mathscr{D}(A)),(B,\mathscr{D}(B)) be two symmetric operators on their corresponding domains. The domain of AB is defined as

\mathscr{D}(AB)\coloneqq\{\psi\in\mathscr{D}(B):B\psi\in\mathscr{D}(A)\}

Since (AB)\psi=A(B\psi), the variance of an operator A relative to a pure state \rho=|\psi\rangle\langle\psi| is given by

\operatorname{Var}_\rho(A)=\operatorname{Tr}(\rho A^2)-\operatorname{Tr}(\rho A)^2=\langle\psi,A^2\psi\rangle-\langle\psi,A\psi\rangle^2

If A is symmetric, then \operatorname{Var}_\rho(A)=\langle A\psi,A\psi\rangle-\langle \psi, A\psi\rangle^2.

Robertson-Schrödinger uncertainty relation for unbounded symmetric operators

Let (A,\mathscr{D}(A)),(B,\mathscr{D}(B)) be two symmetric operators on their corresponding domains. Then

\operatorname{Var}_\rho(A)\operatorname{Var}_\rho(B)\geq\operatorname{Cov}_\rho(A,B)^2+\frac{1}{4}|\mathbb{E}_\rho([A,B])|^2

If \rho is a pure state (\rho=|\psi\rangle\langle\psi| for some unit vector |\psi\rangle\in\mathscr{H}), and the equality holds, then A\psi and B\psi are collinear (i.e. A\psi=c B\psi for some constant c\in\mathbb{R}).

[Proof ignored here]

Summary of analog of classical probability theory and non-commutative (quantum) probability theory

| Classical probability | Non-commutative (Quantum) probability |

|---|---|

Sample space \Omega, cardinality \vert\Omega\vert=n, example: \Omega=\{0,1\} |

Complex Hilbert space \mathscr{H}, dimension \dim\mathscr{H}=n, example: \mathscr{H}=\mathbb{C}^2 |

Common algebra of \mathbb{C} valued functions |

Algebra of bounded operators \mathscr{B}(\mathscr{H}) |

f\mapsto \bar{f} complex conjugation |

P\mapsto P^* adjoint |

| Events: indicator functions of sets | Projections: space of orthogonal projections \mathscr{P}\subseteq\mathscr{B}(\mathscr{H}) |

functions f such that f^2=f=\overline{f} |

orthogonal projections P such that P^*=P=P^2 |

$\mathbb{R}$-valued functions f=\overline{f} |

self-adjoint operators A=A^* |

\mathbb{I}_{f^{-1}(\{\lambda\})} is the indicator function of the set f^{-1}(\{\lambda\}) |

P(\lambda) is the orthogonal projection to eigenspace |

f=\sum_{\lambda\in \operatorname{Range}(f)}\lambda \mathbb{I}_{f^{-1}(\{\lambda\})} |

A=\sum_{\lambda\in \operatorname{sp}(A)}\lambda P(\lambda) |

Probability measure \mu on \Omega |

Density operator \rho on \mathscr{H} |

Delta measure \delta_\omega |

Pure state \rho=\vert\psi\rangle\langle\psi\vert |

\mu is non-negative measure and \sum_{i=1}^n\mu(\{i\})=1 |

\rho is positive semi-definite and \operatorname{Tr}(\rho)=1 |

Expected value of random variable f is \mathbb{E}_{\mu}(f)=\sum_{i=1}^n f(i)\mu(\{i\}) |

Expected value of operator A is \mathbb{E}_\rho(A)=\operatorname{Tr}(\rho A) |

Variance of random variable f is \operatorname{Var}_\mu(f)=\sum_{i=1}^n (f(i)-\mathbb{E}_\mu(f))^2\mu(\{i\}) |

Variance of operator A is \operatorname{Var}_\rho(A)=\operatorname{Tr}(\rho A^2)-\operatorname{Tr}(\rho A)^2 |

Covariance of random variables f and g is \operatorname{Cov}_\mu(f,g)=\sum_{i=1}^n (f(i)-\mathbb{E}_\mu(f))(g(i)-\mathbb{E}_\mu(g))\mu(\{i\}) |

Covariance of operators A and B is \operatorname{Cov}_\rho(A,B)=\operatorname{Tr}(\rho A\circ B)-\operatorname{Tr}(\rho A)\operatorname{Tr}(\rho B) |

Composite system is given by Cartesian product of the sample spaces \Omega_1\times\Omega_2 |

Composite system is given by tensor product of the Hilbert spaces \mathscr{H}_1\otimes\mathscr{H}_2 |

Product measure \mu_1\times\mu_2 on \Omega_1\times\Omega_2 |

Tensor product of space \rho_1\otimes\rho_2 on \mathscr{H}_1\otimes\mathscr{H}_2 |

Marginal distribution \pi_*v |

Partial trace \operatorname{Tr}_2(\rho) |

States of two dimensional system and the complex projective space (Bloch sphere)

Let v=e^{i\theta}u, then the space of pure states (\rho=|u\rangle\langle u|) is the complex projective space \mathbb{C}P^1.

\alpha=x_i+iy_i,\beta=x_2+iy_2 must satisfy |\alpha|^2+|\beta|^2=1, that is x_1^2+x_2^2+y_1^2+y_2^2=1.

The set of unit vectors in \mathbb{C}^2 is the unit sphere in \mathbb{R}^3.

So the space of pure states is the unit circle in \mathbb{R}^2.

Mapping between the space of pure states and the complex projective space

Any two dimensional pure state can be written as e^{i\theta}u, where u is a unit vector in \mathbb{R}^2. There exists a bijective map P:S^2\to\mathscr{P}_1\subseteq M_2(\mathbb{C}) such that P(u)=|u\rangle\langle u|.

P(\vec{x})=\frac{1}{2}(I+\vec{a}\cdot\vec{\sigma})=\frac{1}{2}\begin{pmatrix}

1&0\\

0&1

\end{pmatrix}+\frac{a_x}{2}\begin{pmatrix}

0&1\\

1&0

\end{pmatrix}+\frac{a_y}{2}\begin{pmatrix}

0&-i\\

i&0

\end{pmatrix}+\frac{a_z}{2}\begin{pmatrix}

1&0\\

0&-1

\end{pmatrix}