upgrade structures and migrate to nextra v4

This commit is contained in:

59

content/CSE559A/CSE559A_L1.md

Normal file

59

content/CSE559A/CSE559A_L1.md

Normal file

@@ -0,0 +1,59 @@

|

||||

# CSE559A Lecture 1

|

||||

|

||||

## Introducing the syllabus

|

||||

|

||||

See the syllabus on Canvas.

|

||||

|

||||

## Motivational introduction for computer vision

|

||||

|

||||

Computer vision is the study of manipulating images.

|

||||

|

||||

Automatic understanding of images and videos

|

||||

|

||||

1. vision for measurement (measurement, segmentation)

|

||||

2. vision for perception, interpretation (labeling)

|

||||

3. search and organization (retrieval, image or video archives)

|

||||

|

||||

### What is image

|

||||

|

||||

A 2d array of numbers.

|

||||

|

||||

### Vision is hard

|

||||

|

||||

connection to graphics.

|

||||

|

||||

computer vision need to generate the model from the image.

|

||||

|

||||

#### Are A and B the same color?

|

||||

|

||||

It depends on the context what you mean by "the same".

|

||||

|

||||

todo

|

||||

|

||||

#### Chair detector example.

|

||||

|

||||

double for loops.

|

||||

|

||||

#### Our visual system is not perfect.

|

||||

|

||||

Some optical illusion images.

|

||||

|

||||

todo, embed images here.

|

||||

|

||||

### Ridiculously brief history of computer vision

|

||||

|

||||

1960s: interpretation of synthetic worlds

|

||||

1970s: some progress on interpreting selected images

|

||||

1980s: ANNs come and go; shift toward geometry and increased mathematical rigor

|

||||

1990s: face recognition; statistical analysis in vogue

|

||||

2000s: becoming useful; significant use of machine learning; large annotated datasets available; video processing starts.

|

||||

2010s: Deep learning with ConvNets

|

||||

2020s: String synthesis; continued improvement across tasks, vision-language models.

|

||||

|

||||

## How computer vision is used now

|

||||

|

||||

### OCR, Optical Character Recognition

|

||||

|

||||

Technology to convert scanned docs to text.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

148

content/CSE559A/CSE559A_L10.md

Normal file

148

content/CSE559A/CSE559A_L10.md

Normal file

@@ -0,0 +1,148 @@

|

||||

# CSE559A Lecture 10

|

||||

|

||||

## Convolutional Neural Networks

|

||||

|

||||

### Convolutional Layer

|

||||

|

||||

Output feature map resolution depends on padding and stride

|

||||

|

||||

Padding: add zeros around the input image

|

||||

|

||||

Stride: the step of the convolution

|

||||

|

||||

Example:

|

||||

|

||||

1. Convolutional layer for 5x5 image with 3x3 kernel, padding 1, stride 1 (no skipping pixels)

|

||||

- Input: 5x5 image

|

||||

- Output: 3x3 feature map, (5-3+2*1)/1+1=5

|

||||

2. Convolutional layer for 5x5 image with 3x3 kernel, padding 1, stride 2 (skipping pixels)

|

||||

- Input: 5x5 image

|

||||

- Output: 2x2 feature map, (5-3+2*1)/2+1=2

|

||||

|

||||

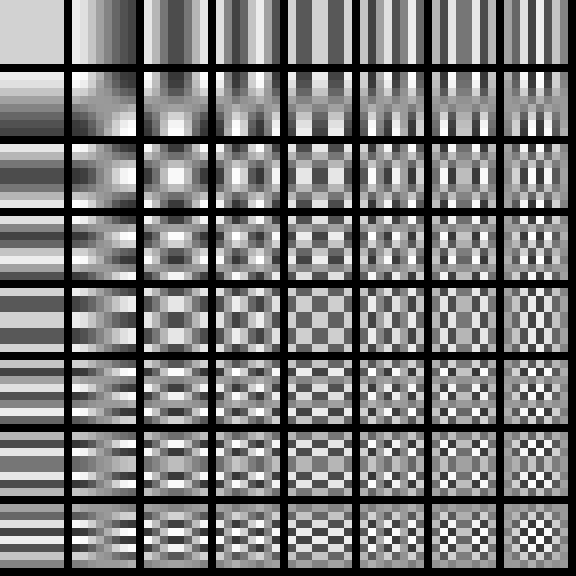

_Learned weights can be thought of as local templates_

|

||||

|

||||

```python

|

||||

import torch

|

||||

import torch.nn as nn

|

||||

|

||||

# suppose input image is HxWx3 (assume RGB image)

|

||||

|

||||

conv_layer = nn.Conv2d(in_channels=3, # input channel, input is HxWx3

|

||||

out_channels=64, # output channel (number of filters), output is HxWx64

|

||||

kernel_size=3, # kernel size

|

||||

padding=1, # padding, this ensures that the output feature map has the same resolution as the input image, H_out=H_in, W_out=W_in

|

||||

stride=1) # stride

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

Usually followed by a ReLU activation function

|

||||

|

||||

```python

|

||||

conv_layer = nn.Conv2d(in_channels=3, out_channels=64, kernel_size=3, padding=1, stride=1)

|

||||

relu = nn.ReLU()

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

Suppose input image is $H\times W\times K$, the output feature map is $H\times W\times L$ with kernel size $F\times F$, this takes $F^2\times K\times L\times H\times W$ parameters

|

||||

|

||||

Each operation $D\times (K^2C)$ matrix with $(K^2C)\times N$ matrix, assume $D$ filters and $C$ output channels.

|

||||

|

||||

### Variants 1x1 convolutions, depthwise convolutions

|

||||

|

||||

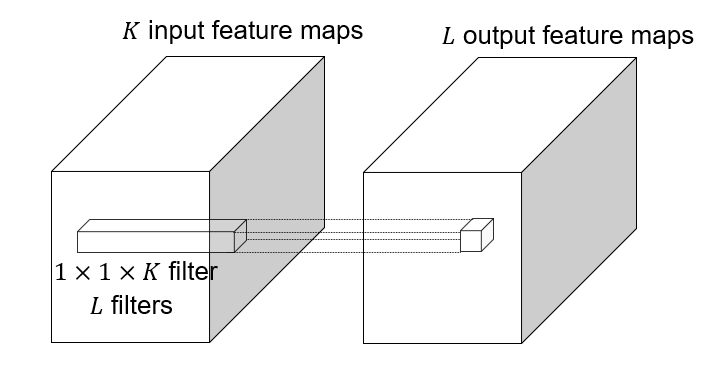

#### 1x1 convolutions

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

1x1 convolution: $F=1$, this layer do convolution in the pixel level, it is **pixel-wise** convolution for the feature.

|

||||

|

||||

Used to save computation, reduce the number of parameters.

|

||||

|

||||

Example: 3x3 conv layer with 256 channels at input and output.

|

||||

|

||||

Option 1: naive way:

|

||||

|

||||

```python

|

||||

conv_layer = nn.Conv2d(in_channels=256, out_channels=256, kernel_size=3, padding=1, stride=1)

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

This takes $256\times 3 \times 3\times 256=524,288$ parameters.

|

||||

|

||||

Option 2: 1x1 convolution:

|

||||

|

||||

```python

|

||||

conv_layer = nn.Conv2d(in_channels=256, out_channels=64, kernel_size=1, padding=0, stride=1)

|

||||

conv_layer = nn.Conv2d(in_channels=64, out_channels=64, kernel_size=3, padding=1, stride=1)

|

||||

conv_layer = nn.Conv2d(in_channels=64, out_channels=256, kernel_size=1, padding=0, stride=1)

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

This takes $256\times 1\times 1\times 64 + 64\times 3\times 3\times 64 + 64\times 1\times 1\times 256 = 16,384 + 36,864 + 16,384 = 69,632$ parameters.

|

||||

|

||||

This lose some information, but save a lot of parameters.

|

||||

|

||||

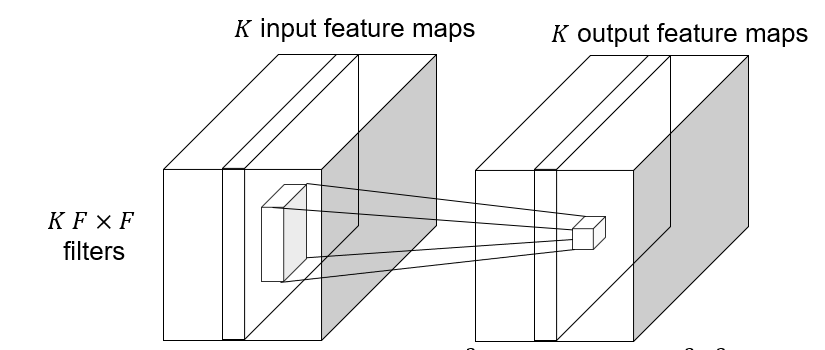

#### Depthwise convolutions

|

||||

|

||||

Depthwise convolution: $K\to K$ feature map, save computation, reduce the number of parameters.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

#### Grouped convolutions

|

||||

|

||||

Self defined convolution on the feature map following the similar manner.

|

||||

|

||||

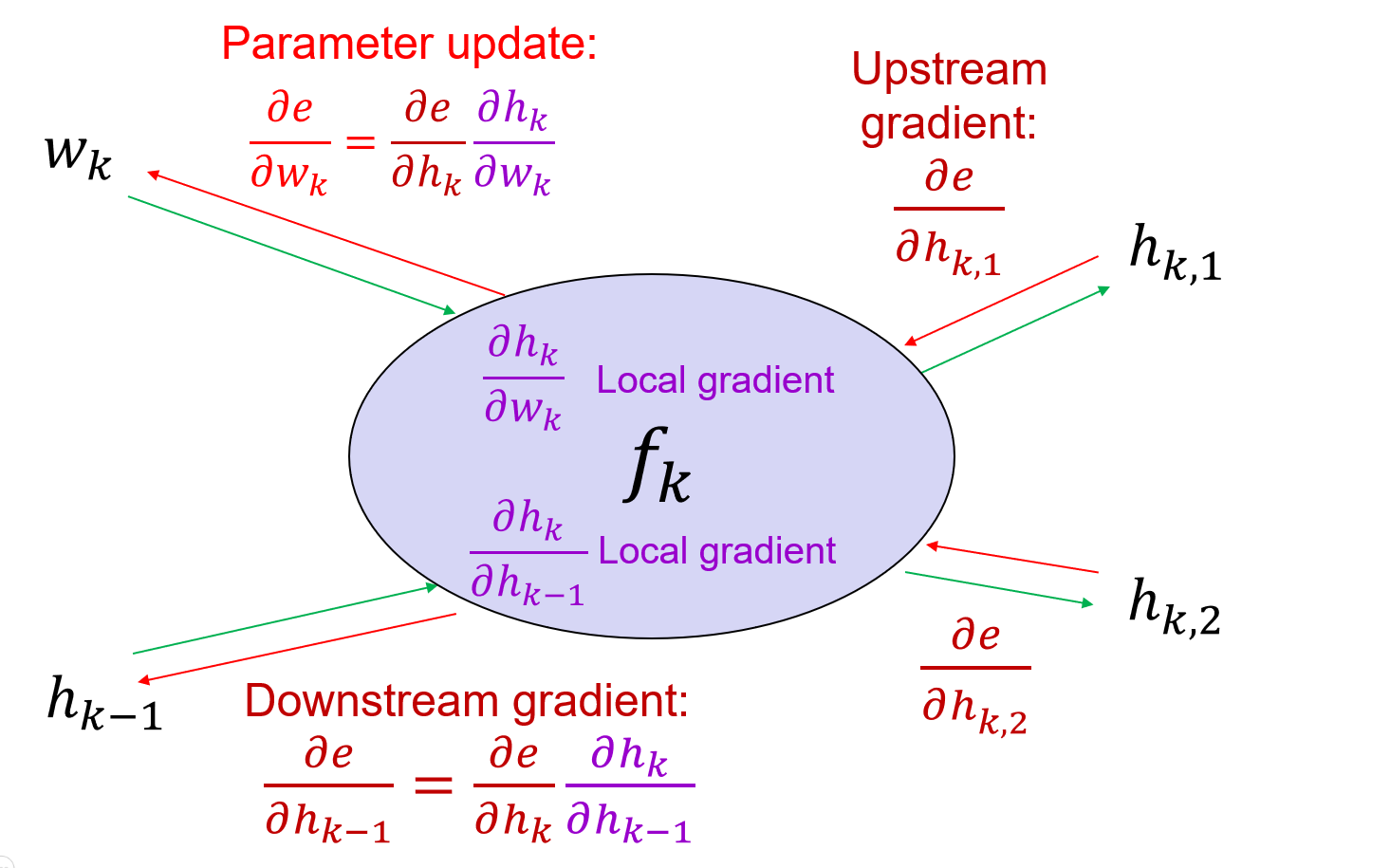

### Backward pass

|

||||

|

||||

Vector-matrix form:

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\frac{\partial e}{\partial x}=\frac{\partial e}{\partial z}\frac{\partial z}{\partial x}

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

Suppose the kernel is 3x3, the feature map is $\ldots, x_{i-1}, x_i, x_{i+1}, \ldots$, and $\ldots, z_{i-1}, z_i, z_{i+1}, \ldots$ is the output feature map, then:

|

||||

|

||||

The convolution operation can be written as:

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

z_i = w_1x_{i-1} + w_2x_i + w_3x_{i+1}

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

The gradient of the kernel is:

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\frac{\partial e}{\partial x_i} = \sum_{j=-1}^{1}\frac{\partial e}{\partial z_i}\frac{\partial z_i}{\partial x_i} = \sum_{j=-1}^{1}\frac{\partial e}{\partial z_i}w_j

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

### Max-pooling

|

||||

|

||||

Get max value in the local region.

|

||||

|

||||

#### Receptive field

|

||||

|

||||

The receptive field of a unit is the region of the input feature map whose values contribute to the response of that unit (either in the previous layer or in the initial image)

|

||||

|

||||

## Architecture of CNNs

|

||||

|

||||

### AlexNet (2012-2013)

|

||||

|

||||

Successor of LeNet-5, but with a few significant changes

|

||||

|

||||

- Max pooling, ReLU nonlinearity

|

||||

- Dropout regularization

|

||||

- More data and bigger model (7 hidden layers, 650K units, 60M params)

|

||||

- GPU implementation (50x speedup over CPU)

|

||||

- Trained on two GPUs for a week

|

||||

|

||||

#### Key points

|

||||

|

||||

Most floating point operations occur in the convolutional layers.

|

||||

|

||||

Most of the memory usage is in the early convolutional layers.

|

||||

|

||||

Nearly all parameters are in the fully-connected layers.

|

||||

|

||||

### VGGNet (2014)

|

||||

|

||||

### GoogLeNet (2014)

|

||||

|

||||

### ResNet (2015)

|

||||

|

||||

### Beyond ResNet (2016 and onward): Wide ResNet, ResNeXT, DenseNet

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

141

content/CSE559A/CSE559A_L11.md

Normal file

141

content/CSE559A/CSE559A_L11.md

Normal file

@@ -0,0 +1,141 @@

|

||||

# CSE559A Lecture 11

|

||||

|

||||

## Continue on Architecture of CNNs

|

||||

|

||||

### AlexNet (2012-2013)

|

||||

|

||||

Successor of LeNet-5, but with a few significant changes

|

||||

|

||||

- Max pooling, ReLU nonlinearity

|

||||

- Dropout regularization

|

||||

- More data and bigger model (7 hidden layers, 650K units, 60M params)

|

||||

- GPU implementation (50x speedup over CPU)

|

||||

- Trained on two GPUs for a week

|

||||

|

||||

#### Architecture for AlexNet

|

||||

|

||||

- Input: 224x224x3

|

||||

- 11x11 conv, stride 4, 96 filters

|

||||

- 3x3 max pooling, stride 2

|

||||

- 5x5 conv, 256 filters, padding 2

|

||||

- 3x3 max pooling, stride 2

|

||||

- 3x3 conv, 384 filters, padding 1

|

||||

- 3x3 conv, 384 filters, padding 1

|

||||

- 3x3 conv, 256 filters, padding 1

|

||||

- 3x3 max pooling, stride 2

|

||||

- 4096-unit FC, ReLU

|

||||

- 4096-unit FC, ReLU

|

||||

- 1000-unit FC, softmax

|

||||

|

||||

#### Key points for AlexNet

|

||||

|

||||

Most floating point operations occur in the convolutional layers.

|

||||

|

||||

Most of the memory usage is in the early convolutional layers.

|

||||

|

||||

Nearly all parameters are in the fully-connected layers.

|

||||

|

||||

#### Further refinement (ZFNet, 2013)

|

||||

|

||||

Best paper award at ILSVRC 2013.

|

||||

|

||||

Nicely visualizes the feature maps.

|

||||

|

||||

### VGGNet (2014)

|

||||

|

||||

All the cov layers are 3x3 filters with stride 1 and padding 1. Take advantage of pooling to reduce the spatial dimensionality.

|

||||

|

||||

#### Architecture for VGGNet

|

||||

|

||||

- Input: 224x224x3

|

||||

- 3x3 conv, 64 filters, padding 1

|

||||

- 3x3 conv, 64 filters, padding 1

|

||||

- 2x2 max pooling, stride 2

|

||||

- 3x3 conv, 128 filters, padding 1

|

||||

- 3x3 conv, 128 filters, padding 1

|

||||

- 2x2 max pooling, stride 2

|

||||

- 3x3 conv, 256 filters, padding 1

|

||||

- 3x3 conv, 256 filters, padding 1

|

||||

- 2x2 max pooling, stride 2

|

||||

- 3x3 conv, 512 filters, padding 1

|

||||

- 3x3 conv, 512 filters, padding 1

|

||||

- 3x3 conv, 512 filters, padding 1

|

||||

- 2x2 max pooling, stride 2

|

||||

- 3x3 conv, 512 filters, padding 1

|

||||

- 3x3 conv, 512 filters, padding 1

|

||||

- 3x3 conv, 512 filters, padding 1

|

||||

- 2x2 max pooling, stride 2

|

||||

- 4096-unit FC, ReLU

|

||||

- 4096-unit FC, ReLU

|

||||

- 1000-unit FC, softmax

|

||||

|

||||

#### Key points for VGGNet

|

||||

|

||||

- Sequence of deeper networks trained progressively

|

||||

- Large receptive fields replaced by successive layer of 3x3 convs with relu in between

|

||||

- 7x7 takes $49K^2$ parameters, 3x3 takes $27K^2$ parameters

|

||||

|

||||

#### Pretrained models

|

||||

|

||||

- Use pretrained-network as feature extractor (removing the last layer and training a new linear layer) (transfer learning)

|

||||

- Add RNN layers to generate captions

|

||||

- Fine-tune the model for the new task (finetuning)

|

||||

- Keep the earlier layers fixed and only train the new prediction layer

|

||||

|

||||

### GoogLeNet (2014)

|

||||

|

||||

Stem network at the start aggressively downsamples input.

|

||||

|

||||

#### Key points for GoogLeNet

|

||||

|

||||

- Parallel paths with different receptive field size and operations are means to capture space patterns of correlations in the stack of feature maps

|

||||

- Use 1x1 convs to reduce dimensionality

|

||||

- Use Global Average Pooling (GAP) to replace the fully connected layer

|

||||

- Auxiliary classifiers to improve training

|

||||

- Training using loss at the end of the network didn't work well: network is too deep, gradient don't provide useful model updates

|

||||

- As a hack, attach "auxiliary classifiers" at several intermediate points in the network that also try to classify the image and receive loss

|

||||

- _GooLeNet was before batch normalization, with batch normalization, the auxiliary classifiers were removed._

|

||||

|

||||

### ResNet (2015)

|

||||

|

||||

152 layers

|

||||

|

||||

[ResNet paper](https://arxiv.org/abs/1512.03385)

|

||||

|

||||

#### Key points for ResNet

|

||||

|

||||

- The residual module

|

||||

- Introduce `skip` or `shortcut` connections to avoid the degradation problem

|

||||

- Make it easy for network layers to represent the identity mapping

|

||||

- Directly performing 3×3 convolutions with 256 feature maps at input and output:

|

||||

- $256 \times 256 \times 3 \times 3 \approx 600K$ operations

|

||||

- Using 1×1 convolutions to reduce 256 to 64 feature maps, followed by 3×3 convolutions, followed by 1×1 convolutions to expand back to 256 maps:

|

||||

- $256 \times 64 \times 1 \times 1 \approx 16K$

|

||||

- $64 \times 64 \times 3 \times 3 \approx 36K$

|

||||

- $64 \times 256 \times 1 \times 1 \approx 16K$

|

||||

- Total $\approx 70K$

|

||||

|

||||

_Possibly the first model with top-5 error rate better than human performance._

|

||||

|

||||

### Beyond ResNet (2016 and onward): Wide ResNet, ResNeXT, DenseNet

|

||||

|

||||

#### Wide ResNet

|

||||

|

||||

Reduce number of residual blocks, but increase number of feature maps in each block

|

||||

|

||||

- More parallelizable, better feature reuse

|

||||

- 16-layer WRN outperforms 1000-layer ResNets, though with much larger # of parameters

|

||||

|

||||

#### ResNeXt

|

||||

|

||||

- Propose “cardinality” as a new factor in network design, apart from depth and width

|

||||

- Claim that increasing cardinality is a better way to increase capacity than increasing depth or width

|

||||

|

||||

#### DenseNet

|

||||

|

||||

- Use Dense block between conv layers

|

||||

- Less parameters than ResNet

|

||||

|

||||

Next class:

|

||||

|

||||

Transformer architectures

|

||||

159

content/CSE559A/CSE559A_L12.md

Normal file

159

content/CSE559A/CSE559A_L12.md

Normal file

@@ -0,0 +1,159 @@

|

||||

# CSE559A Lecture 12

|

||||

|

||||

## Transformer Architecture

|

||||

|

||||

### Outline

|

||||

|

||||

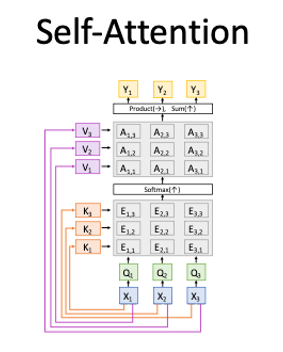

**Self-Attention Layers**: An important network module, which often has a global receptive field

|

||||

|

||||

**Sequential Input Tokens**: Breaking the restriction to 2d input arrays

|

||||

|

||||

**Positional Encodings**: Representing the metadata of each input token

|

||||

|

||||

**Exemplar Architecture**: The Vision Transformer (ViT)

|

||||

|

||||

**Moving Forward**: What does this new module enable? Who wins in the battle between transformers and CNNs?

|

||||

|

||||

### The big picture

|

||||

|

||||

CNNs

|

||||

|

||||

- Local receptive fields

|

||||

- Struggles with global content

|

||||

- Shape of intermediate layers is sometimes a pain

|

||||

|

||||

Things we might want:

|

||||

|

||||

- Use information from across the image

|

||||

- More flexible shape handling

|

||||

- Multiple modalities

|

||||

|

||||

Our Hero: MultiheadAttention

|

||||

|

||||

Use positional encodings to represent the metadata of each input token

|

||||

|

||||

## Self-Attention layers

|

||||

|

||||

### Comparing with ways to handling sequential data

|

||||

|

||||

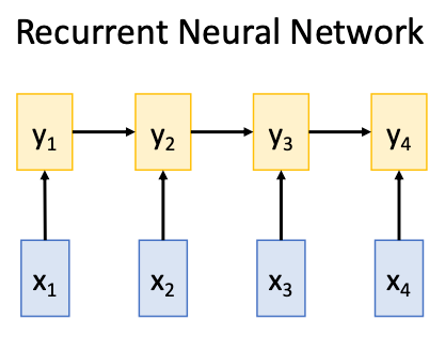

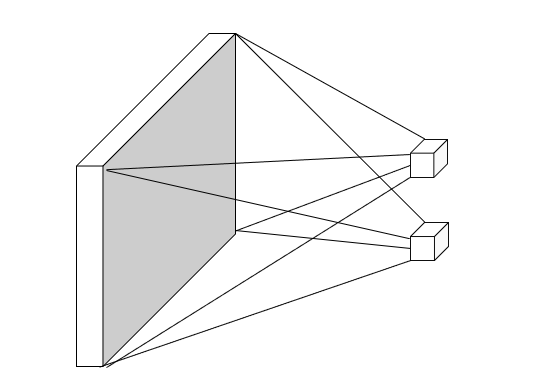

#### RNN

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

Works on **Ordered Sequences**

|

||||

|

||||

- Good at long sequences: After one RNN layer $h_r$ sees the whole sequence

|

||||

- Bad at parallelization: need to compute hidden states sequentially

|

||||

|

||||

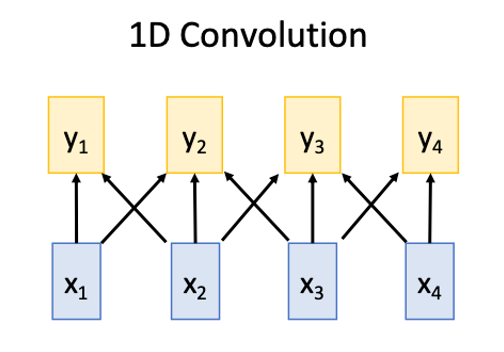

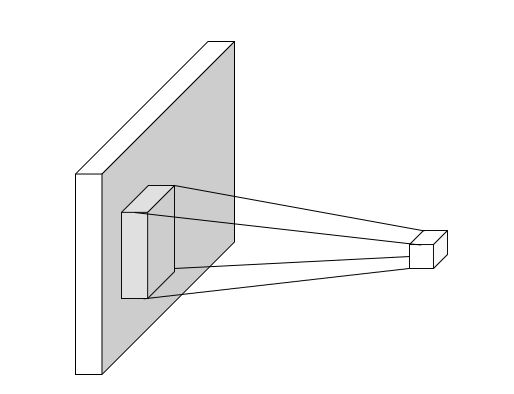

#### 1D conv

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

Works on **Multidimensional Grids**

|

||||

|

||||

- Bad at long sequences: Need to stack may conv layers or outputs to see the whole sequence

|

||||

- Good at parallelization: Each output can be computed in parallel

|

||||

|

||||

#### Self-Attention

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

Works on **Set of Vectors**

|

||||

|

||||

- Good at Long sequences: Each output can attend to all inputs

|

||||

- Good at parallelization: Each output can be computed in parallel

|

||||

- Bad at saving memory: Need to store all inputs in memory

|

||||

|

||||

### Encoder-Decoder Architecture

|

||||

|

||||

The encoder is constructed by stacking multiple self-attention layers and feed-forward networks.

|

||||

|

||||

#### Word Embeddings

|

||||

|

||||

Translate tokens to vector space

|

||||

|

||||

```python

|

||||

class Embedder(nn.Module):

|

||||

def __init__(self, vocab_size, d_model):

|

||||

super().__init__()

|

||||

self.embed=nn.Embedding(vocab_size, d_model)

|

||||

|

||||

def forward(self, x):

|

||||

return self.embed(x)

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

#### Positional Embeddings

|

||||

|

||||

The positional encodings are a way to represent the position of each token in the sequence.

|

||||

|

||||

Combined with the word embeddings, we get the input to the self-attention layer with information about the position of each token in the sequence.

|

||||

|

||||

> The reason why we just add the positional encodings to the word embeddings is _perhaps_ that we want the model to self-assign weights to the word-token and positional-token.

|

||||

|

||||

#### Query, Key, Value

|

||||

|

||||

The query, key, and value are the three components of the self-attention layer.

|

||||

|

||||

They are used to compute the attention weights.

|

||||

|

||||

```python

|

||||

class SelfAttention(nn.Module):

|

||||

def __init__(self, d_model, num_heads):

|

||||

super().__init__()

|

||||

self.d_model = d_model

|

||||

self.d_k = d_k

|

||||

self.q_linear = nn.Linear(d_model, d_k)

|

||||

self.k_linear = nn.Linear(d_model, d_k)

|

||||

self.v_linear = nn.Linear(d_model, d_k)

|

||||

self.dropout = nn.Dropout(dropout)

|

||||

self.out = nn.Linear(d_k, d_k)

|

||||

|

||||

def forward(self, q, k, v, mask=None):

|

||||

|

||||

bs = q.size(0)

|

||||

|

||||

k = self.k_linear(k)

|

||||

q = self.q_linear(q)

|

||||

v = self.v_linear(v)

|

||||

|

||||

# calculate attention weights

|

||||

outputs = attention(q, k, v, self.d_k, mask, self.dropout)

|

||||

|

||||

# apply output linear transformation

|

||||

outputs = self.out(outputs)

|

||||

|

||||

return outputs

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

#### Attention

|

||||

|

||||

```python

|

||||

def attention(q, k, v, d_k, mask=None, dropout=None):

|

||||

scores = torch.matmul(q, k.transpose(-2, -1)) / math.sqrt(d_k)

|

||||

|

||||

if mask is not None:

|

||||

mask = mask.unsqueeze(1)

|

||||

scores = scores.masked_fill(mask == 0, -1e9)

|

||||

|

||||

scores = F.softmax(scores, dim=-1)

|

||||

|

||||

if dropout is not None:

|

||||

scores = dropout(scores)

|

||||

|

||||

outputs = torch.matmul(scores, v)

|

||||

|

||||

return outputs

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

The query, key are used to compute the attention map, and the value is used to compute the attention output.

|

||||

|

||||

#### Multi-Head self-attention

|

||||

|

||||

The multi-head self-attention is a self-attention layer that has multiple heads.

|

||||

|

||||

Each head has its own query, key, and value.

|

||||

|

||||

### Computing Attention Efficiency

|

||||

|

||||

- the standard attention has a complexity of $O(n^2)$

|

||||

- We can use sparse attention to reduce the complexity to $O(n)$

|

||||

59

content/CSE559A/CSE559A_L13.md

Normal file

59

content/CSE559A/CSE559A_L13.md

Normal file

@@ -0,0 +1,59 @@

|

||||

# CSE559A Lecture 13

|

||||

|

||||

## Positional Encodings

|

||||

|

||||

### Fixed Positional Encodings

|

||||

|

||||

Set of sinusoids of different frequencies.

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

f(p,2i)=\sin(\frac{p}{10000^{2i/d}})\quad f(p,2i+1)=\cos(\frac{p}{10000^{2i/d}})

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

[source](https://kazemnejad.com/blog/transformer_architecture_positional_encoding/)

|

||||

|

||||

### Positional Encodings in Reconstruction

|

||||

|

||||

MLP is hard to learn high-frequency information from scaler input $(x,y)$.

|

||||

|

||||

Example: network mapping from $(x,y)$ to $(r,g,b)$.

|

||||

|

||||

### Generalized Positional Encodings

|

||||

|

||||

- Dependence on location, scaler, metadata, etc.

|

||||

- Can just be fully learned (use `nn.Embedding` and optimize based on a categorical input.)

|

||||

|

||||

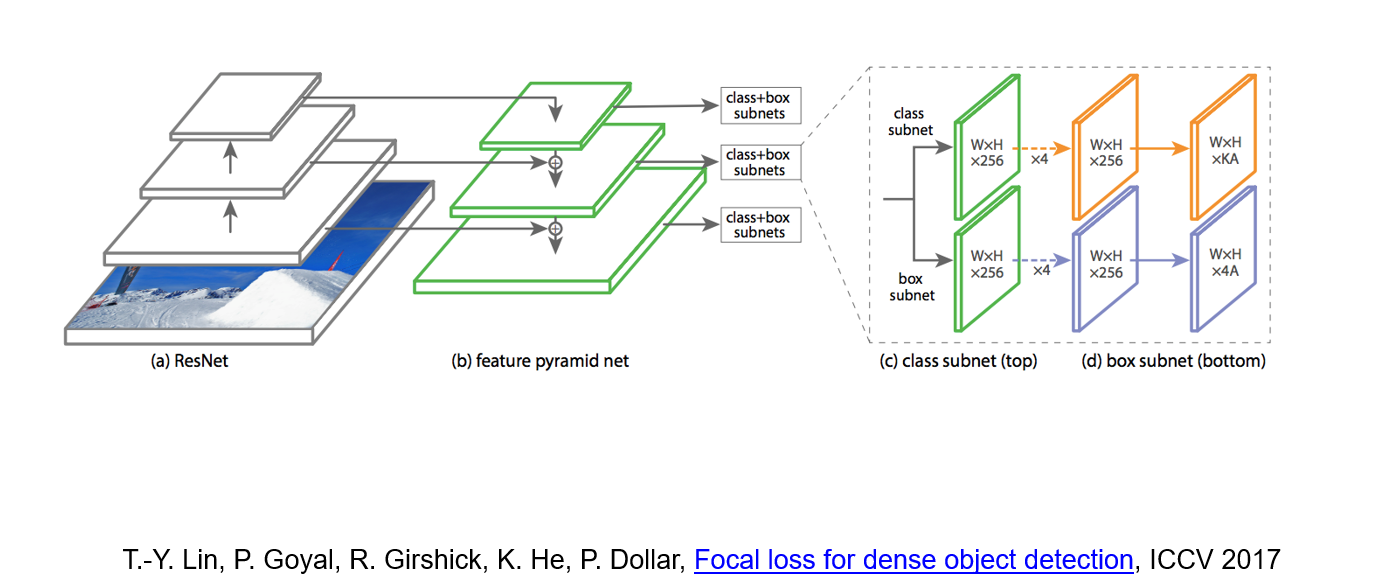

## Vision Transformer (ViT)

|

||||

|

||||

### Class Token

|

||||

|

||||

In Vision Transformers, a special token called the class token is added to the input sequence to aggregate information for classification tasks.

|

||||

|

||||

### Hidden CNN Modules

|

||||

|

||||

- PxP convolution with stride P (split the image into patches and use positional encoding)

|

||||

|

||||

### ViT + ResNet Hybrid

|

||||

|

||||

Build a hybrid model that combines the vision transformer after 50 layer of ResNet.

|

||||

|

||||

## Moving Forward

|

||||

|

||||

At least for now, CNN and ViT architectures have similar performance at least in ImageNet.

|

||||

|

||||

- General Consensus: once the architecture is big enough, and not designed terribly, it can do well.

|

||||

- Differences remain:

|

||||

- Computational efficiency

|

||||

- Ease of use in other tasks and with other input data

|

||||

- Ease of training

|

||||

|

||||

## Wrap up

|

||||

|

||||

Self attention as a key building block

|

||||

|

||||

Flexible input specification using tokens with positional encodings

|

||||

|

||||

A wide variety of architectural styles

|

||||

|

||||

Up Next:

|

||||

Training deep neural networks

|

||||

73

content/CSE559A/CSE559A_L14.md

Normal file

73

content/CSE559A/CSE559A_L14.md

Normal file

@@ -0,0 +1,73 @@

|

||||

# CSE559A Lecture 14

|

||||

|

||||

## Object Detection

|

||||

|

||||

AP (Average Precision)

|

||||

|

||||

### Benchmarks

|

||||

|

||||

#### PASCAL VOC Challenge

|

||||

|

||||

20 Challenge classes.

|

||||

|

||||

CNN increases the accuracy of object detection.

|

||||

|

||||

#### COCO dataset

|

||||

|

||||

Common objects in context.

|

||||

|

||||

Semantic segmentation. Every pixel is classified to tags.

|

||||

|

||||

Instance segmentation. Every pixel is classified and grouped into instances.

|

||||

|

||||

### Object detection: outline

|

||||

|

||||

Proposal generation

|

||||

|

||||

Object recognition

|

||||

|

||||

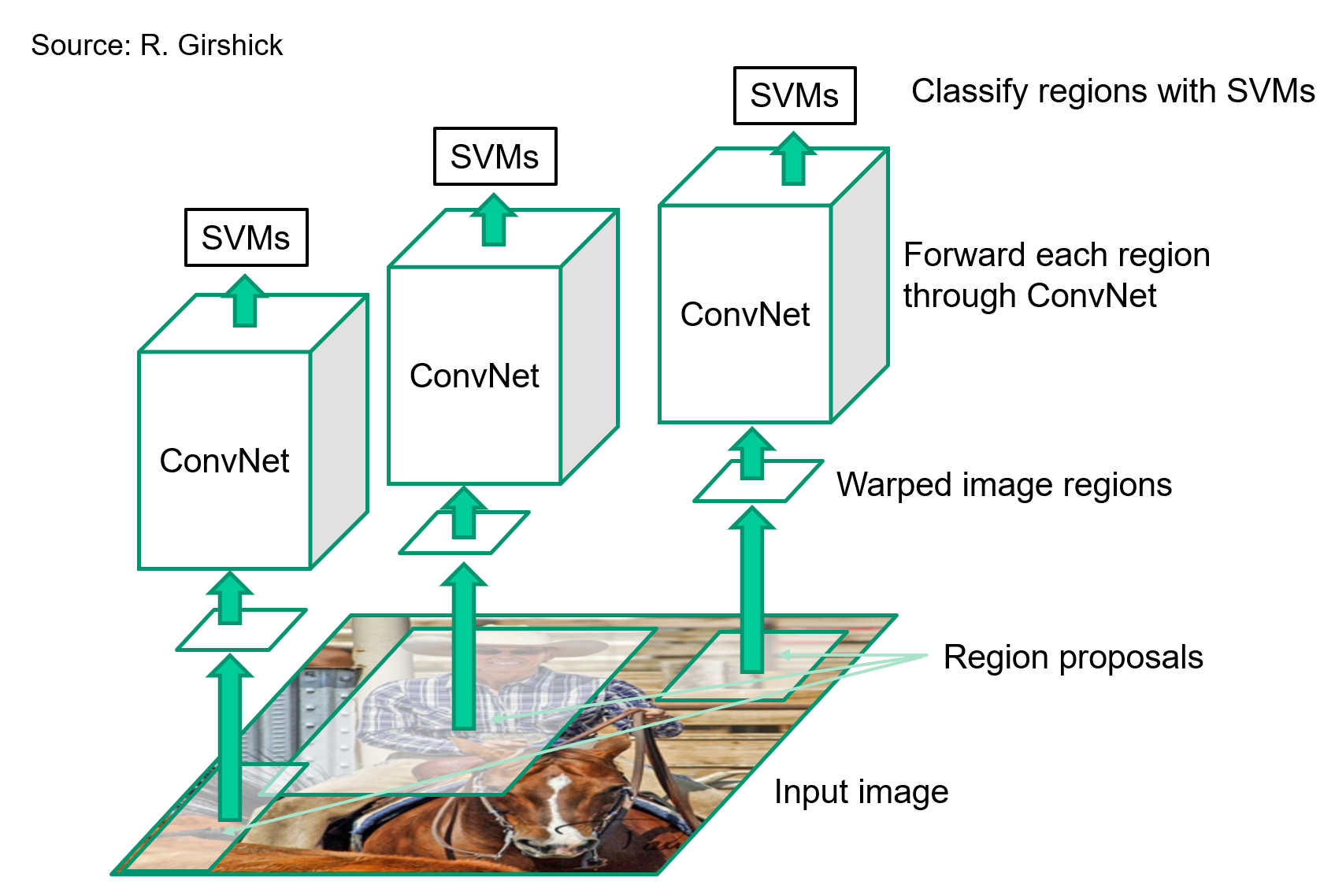

#### R-CNN

|

||||

|

||||

Proposal generation

|

||||

|

||||

Use CNN to extract features from proposals.

|

||||

|

||||

with SVM to classify proposals.

|

||||

|

||||

Use selective search to generate proposals.

|

||||

|

||||

Use AlexNet finetuned on PASCAL VOC to extract features.

|

||||

|

||||

Pros:

|

||||

|

||||

- Much more accurate than previous approaches

|

||||

- Andy deep architecture can immediately be "plugged in"

|

||||

|

||||

Cons:

|

||||

|

||||

- Not a single end-to-end trainable system

|

||||

- Fine-tune network with softmax classifier (log loss)

|

||||

- Train post-hoc linear SVMs (hinge loss)

|

||||

- Train post-hoc bounding box regressors (least squares)

|

||||

- Training is slow 2000CNN passes for each image

|

||||

- Inference (detection) was slow

|

||||

|

||||

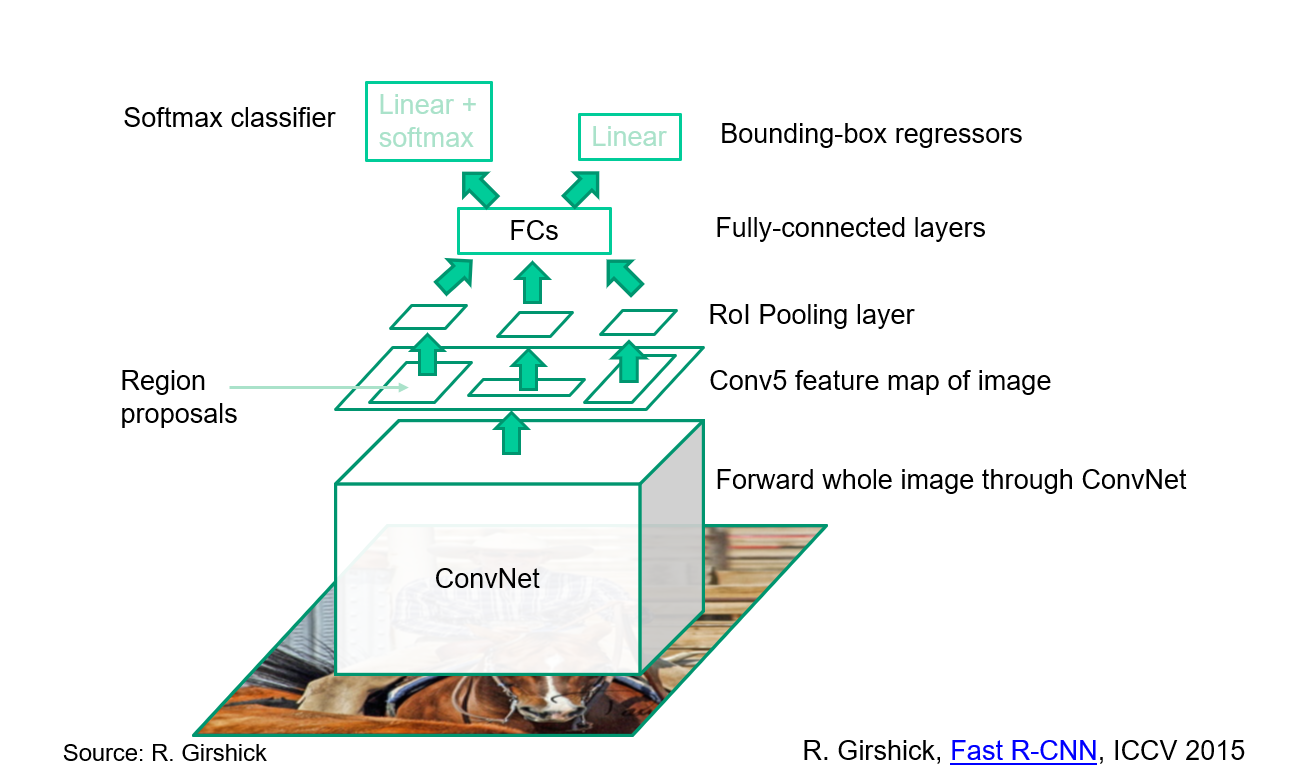

#### Fast R-CNN

|

||||

|

||||

Proposal generation

|

||||

|

||||

Use CNN to extract features from proposals.

|

||||

|

||||

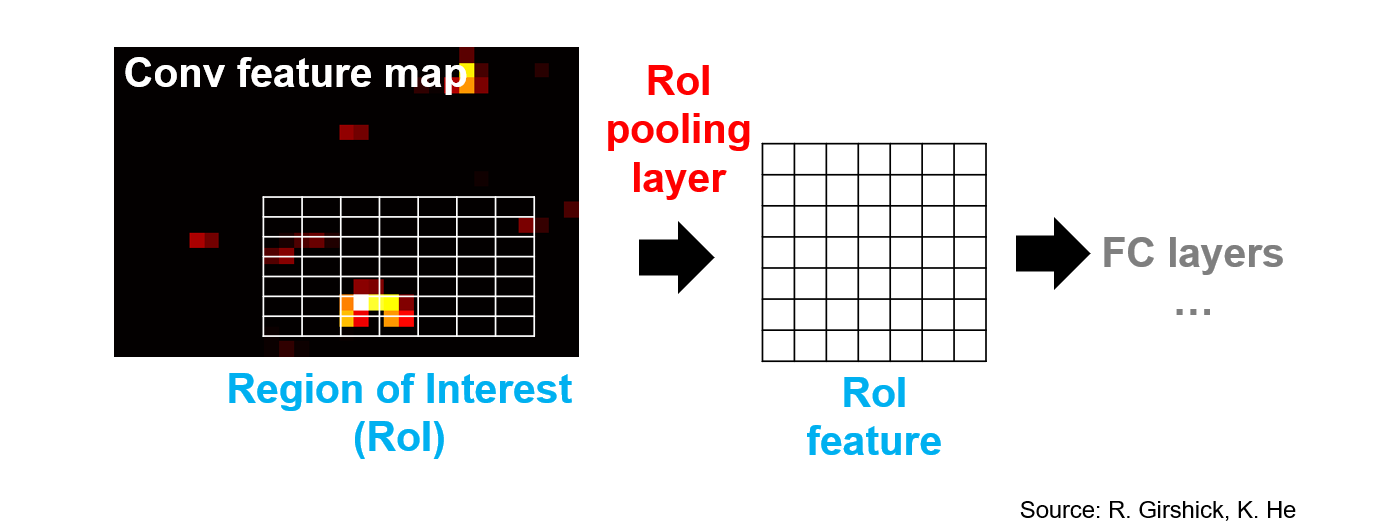

##### ROI pooling and ROI alignment

|

||||

|

||||

ROI pooling:

|

||||

|

||||

- Pooling is applied to the feature map.

|

||||

- Pooling is applied to the proposal.

|

||||

|

||||

ROI alignment:

|

||||

|

||||

- Align the proposal to the feature map.

|

||||

- Align the proposal to the feature map.

|

||||

|

||||

Use bounding box regression to refine the proposal.

|

||||

131

content/CSE559A/CSE559A_L15.md

Normal file

131

content/CSE559A/CSE559A_L15.md

Normal file

@@ -0,0 +1,131 @@

|

||||

# CSE559A Lecture 15

|

||||

|

||||

## Continue on object detection

|

||||

|

||||

### Two strategies for object detection

|

||||

|

||||

#### R-CNN: Region proposals + CNN features

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

#### Fast R-CNN: CNN features + RoI pooling

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

Use bilinear interpolation to get the features of the proposal.

|

||||

|

||||

#### Region of interest pooling

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

Use backpropagation to get the gradient of the proposal.

|

||||

|

||||

### New materials

|

||||

|

||||

#### Faster R-CNN

|

||||

|

||||

Use one CNN to generate region proposals. And use another CNN to classify the proposals.

|

||||

|

||||

##### Region proposal network

|

||||

|

||||

Idea: put an "anchor box" of fixed size over each position in the feature map and try to predict whether this box is likely to contain an object.

|

||||

|

||||

Introduce anchor boxes at multiple scales and aspect ratios to handle a wider range of object sizes and shapes.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

### Single-stage and multi-resolution detection

|

||||

|

||||

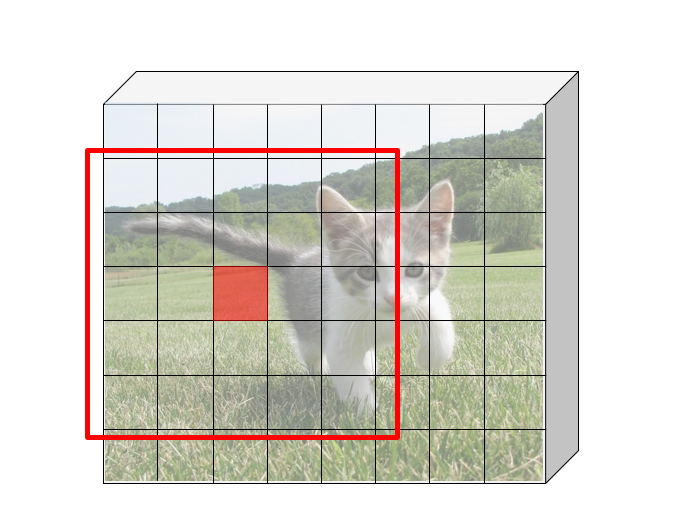

#### YOLO

|

||||

|

||||

You only look once (YOLO) is a state-of-the-art, real-time object detection system.

|

||||

|

||||

1. Take conv feature maps at 7x7 resolution

|

||||

2. Add two FC layers to predict, at each location, a score for each class and 2 bboxes with confidences

|

||||

|

||||

For PASCAL, output is 7×7×30 (30=20 + 2∗(4+1))

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

##### YOLO Network Head

|

||||

|

||||

```python

|

||||

model.add(Conv2D(1024, (3, 3), activation='lrelu', kernel_regularizer=l2(0.0005)))

|

||||

model.add(Conv2D(1024, (3, 3), activation='lrelu', kernel_regularizer=l2(0.0005)))

|

||||

# use flatten layer for global reasoning

|

||||

model.add(Flatten())

|

||||

model.add(Dense(512))

|

||||

model.add(Dense(1024))

|

||||

model.add(Dropout(0.5))

|

||||

model.add(Dense(7 * 7 * 30, activation='sigmoid'))

|

||||

model.add(YOLO_Reshape(target_shape=(7, 7, 30)))

|

||||

model.summary()

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

#### YOLO results

|

||||

|

||||

1. Each grid cell predicts only two boxes and can only have one class – this limits the number of nearby objects that can be predicted

|

||||

2. Localization accuracy suffers compared to Fast(er) R-CNN due to coarser features, errors on small boxes

|

||||

3. 7x speedup over Faster R-CNN (45-155 FPS vs. 7-18 FPS)

|

||||

|

||||

#### YOLOv2

|

||||

|

||||

1. Remove FC layer, do convolutional prediction with anchor boxes instead

|

||||

2. Increase resolution of input images and conv feature maps

|

||||

3. Improve accuracy using batch normalization and other tricks

|

||||

|

||||

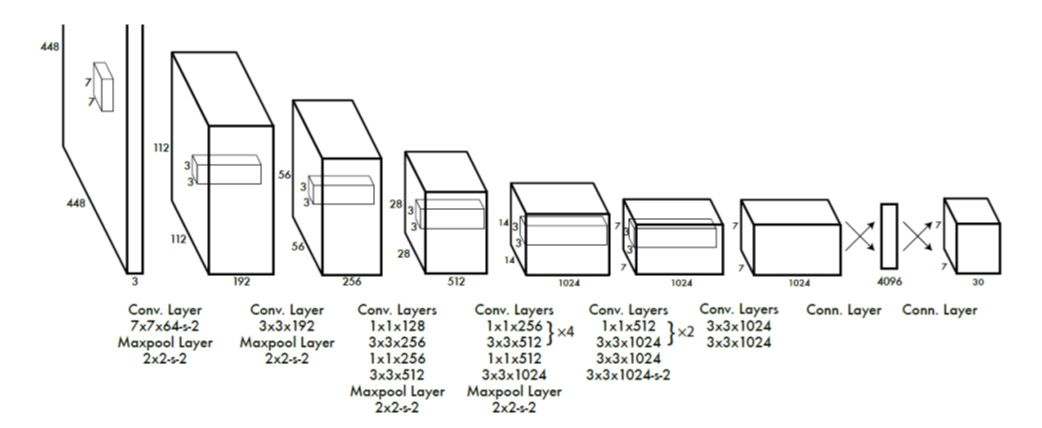

#### SSD

|

||||

|

||||

SSD is a multi-resolution object detection

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

1. Predict boxes of different size from different conv maps

|

||||

2. Each level of resolution has its own predictor

|

||||

|

||||

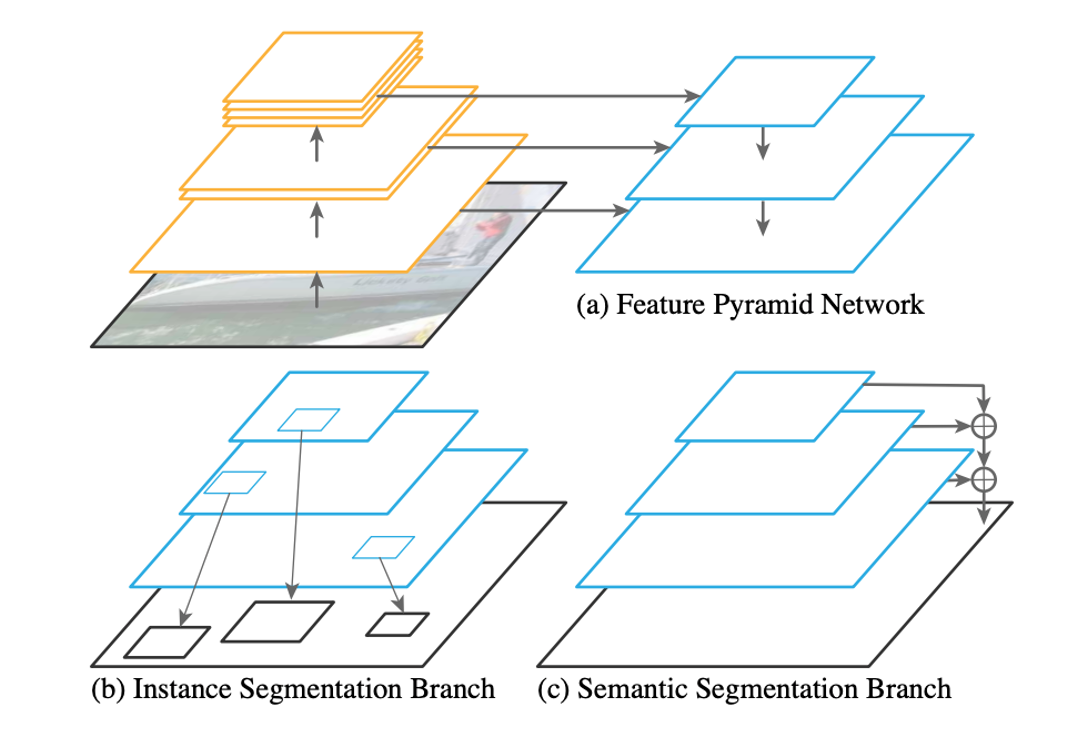

##### Feature Pyramid Network

|

||||

|

||||

- Improve predictive power of lower-level feature maps by adding contextual information from higher-level feature maps

|

||||

- Predict different sizes of bounding boxes from different levels of the pyramid (but share parameters of predictors)

|

||||

|

||||

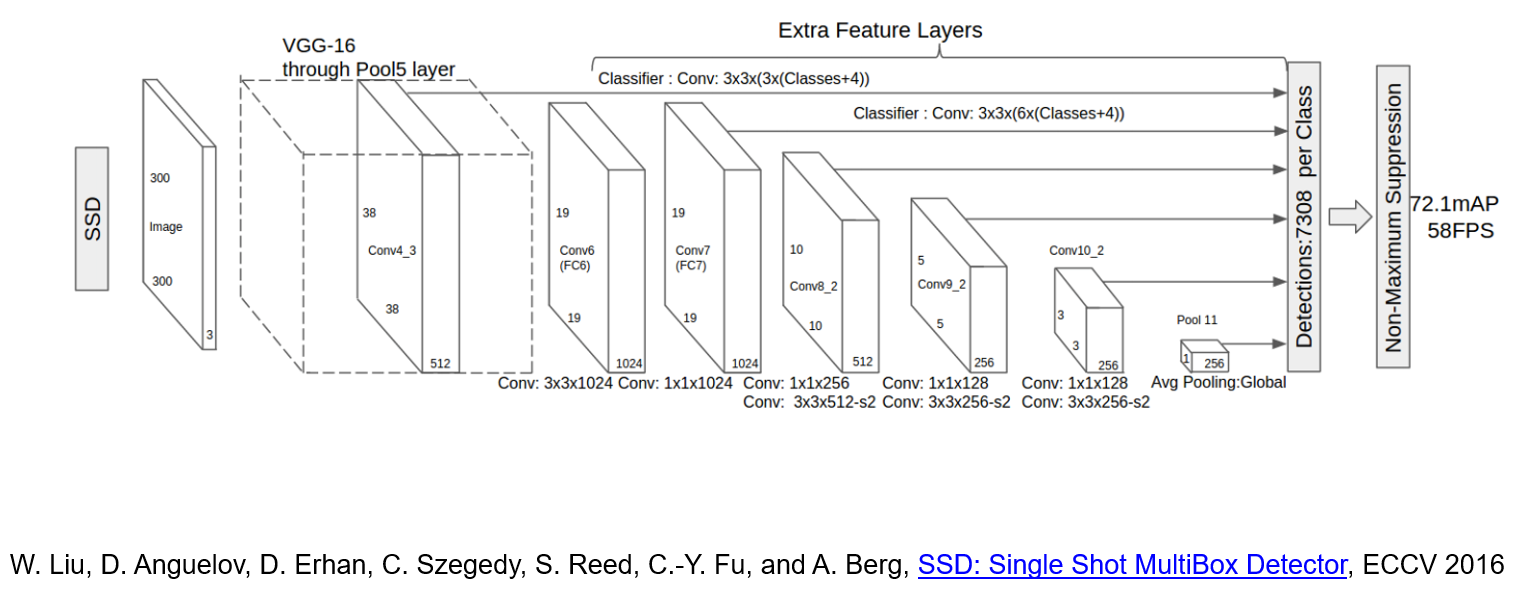

#### RetinaNet

|

||||

|

||||

RetinaNet combine feature pyramid network with focal loss to reduce the standard cross-entropy loss for well-classified examples.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

> Cross-entropy loss:

|

||||

> $$CE(p_t) = - \log(p_t)$$

|

||||

|

||||

The focal loss is defined as:

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

FL(p_t) = - (1 - p_t)^{\gamma} \log(p_t)

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

We can increase $\gamma$ to reduce the loss for well-classified examples.

|

||||

|

||||

#### YOLOv3

|

||||

|

||||

Minor refinements

|

||||

|

||||

### Alternative approaches

|

||||

|

||||

#### CornerNet

|

||||

|

||||

Use a pair of corners to represent the bounding box.

|

||||

|

||||

Use hourglass network to accumulate the information of the corners.

|

||||

|

||||

#### CenterNet

|

||||

|

||||

Use a center point to represent the bounding box.

|

||||

|

||||

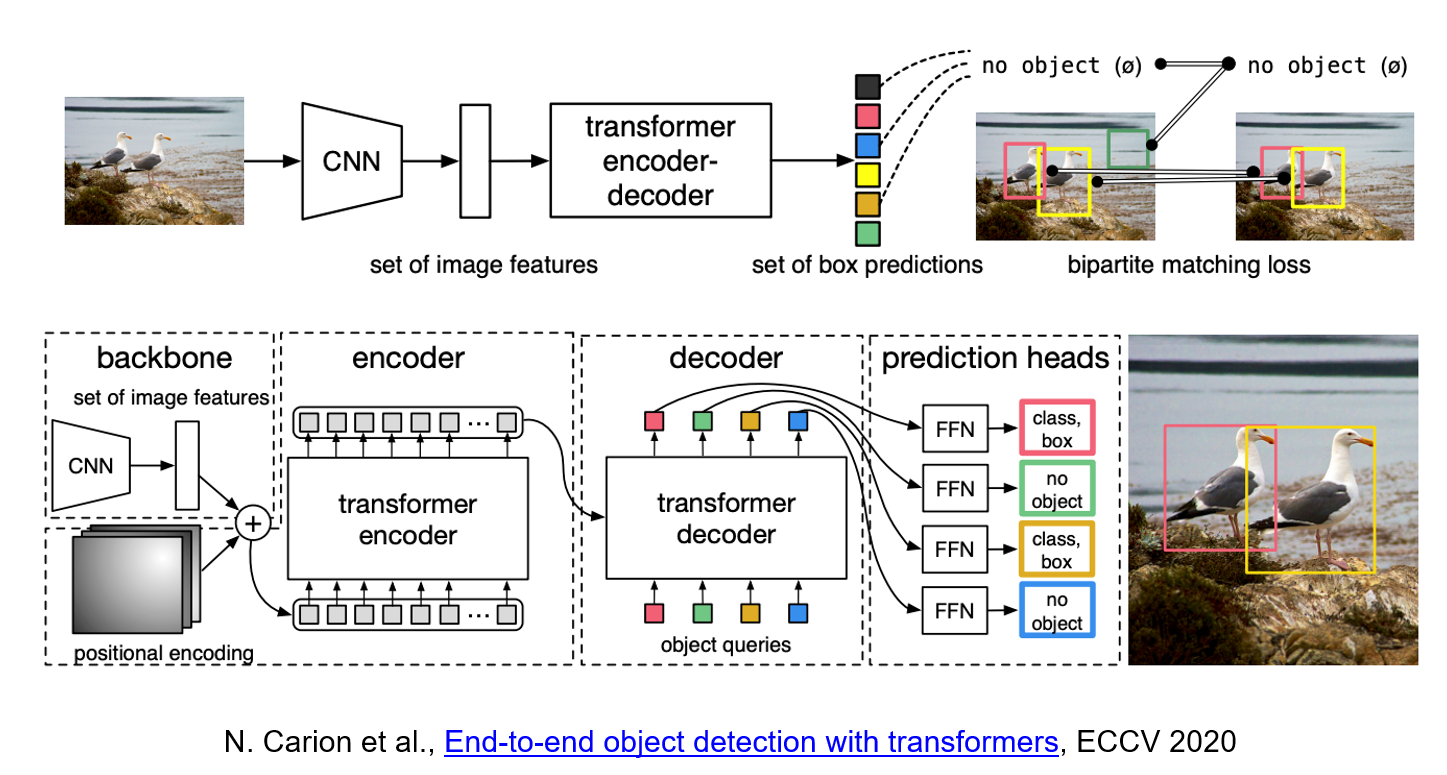

#### Detection Transformer

|

||||

|

||||

Use transformer architecture to detect the object.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

DETR uses a conventional CNN backbone to learn a 2D representation of an input image. The model flattens it and supplements it with a positional encoding before passing it into a transformer encoder. A transformer decoder then takes as input a small fixed number of learned positional embeddings, which we call object queries, and additionally attends to the encoder output. We pass each output embedding of the decoder to a shared feed forward network (FFN) that predicts either a detection (class and bounding box) or a "no object" class.

|

||||

|

||||

114

content/CSE559A/CSE559A_L16.md

Normal file

114

content/CSE559A/CSE559A_L16.md

Normal file

@@ -0,0 +1,114 @@

|

||||

# CSE559A Lecture 16

|

||||

|

||||

## Dense image labelling

|

||||

|

||||

### Semantic segmentation

|

||||

|

||||

Use one-hot encoding to represent the class of each pixel.

|

||||

|

||||

### General Network design

|

||||

|

||||

Design a network with only convolutional layers, make predictions for all pixels at once.

|

||||

|

||||

Can the network operate at full image resolution?

|

||||

|

||||

Practical solution: first downsample, then upsample

|

||||

|

||||

### Outline

|

||||

|

||||

- Upgrading a Classification Network to Segmentation

|

||||

- Operations for dense prediction

|

||||

- Transposed convolutions, unpooling

|

||||

- Architectures for dense prediction

|

||||

- DeconvNet, U-Net, "U-Net"

|

||||

- Instance segmentation

|

||||

- Mask R-CNN

|

||||

- Other dense prediction problems

|

||||

|

||||

### Fully Convolutional Networks

|

||||

|

||||

"upgrading" a classification network to a dense prediction network

|

||||

|

||||

1. Covert "fully connected" layers to 1x1 convolutions

|

||||

2. Make the input image larger

|

||||

3. Upsample the output

|

||||

|

||||

Start with an existing classification CNN ("an encoder")

|

||||

|

||||

Then use bilinear interpolation and transposed convolutions to make full resolution.

|

||||

|

||||

### Operations for dense prediction

|

||||

|

||||

#### Transposed Convolutions

|

||||

|

||||

Use the filter to "paint" in the output: place copies of the filter on the output, multiply by corresponding value in the input, sum where copies of the filter overlap

|

||||

|

||||

We can increase the resolution of the output by using a larger stride in the convolution.

|

||||

|

||||

- For stride 2, dilate the input by inserting rows and columns of zeros between adjacent entries, convolve with flipped filter

|

||||

- Sometimes called convolution with fractional input stride 1/2

|

||||

|

||||

#### Unpooling

|

||||

|

||||

Max unpooling:

|

||||

|

||||

- Copy the maximum value in the input region to all locations in the output

|

||||

- Use the location of the maximum value to know where to put the value in the output

|

||||

|

||||

Nearest neighbor unpooling:

|

||||

|

||||

- Copy the maximum value in the input region to all locations in the output

|

||||

- Use the location of the maximum value to know where to put the value in the output

|

||||

|

||||

### Architectures for dense prediction

|

||||

|

||||

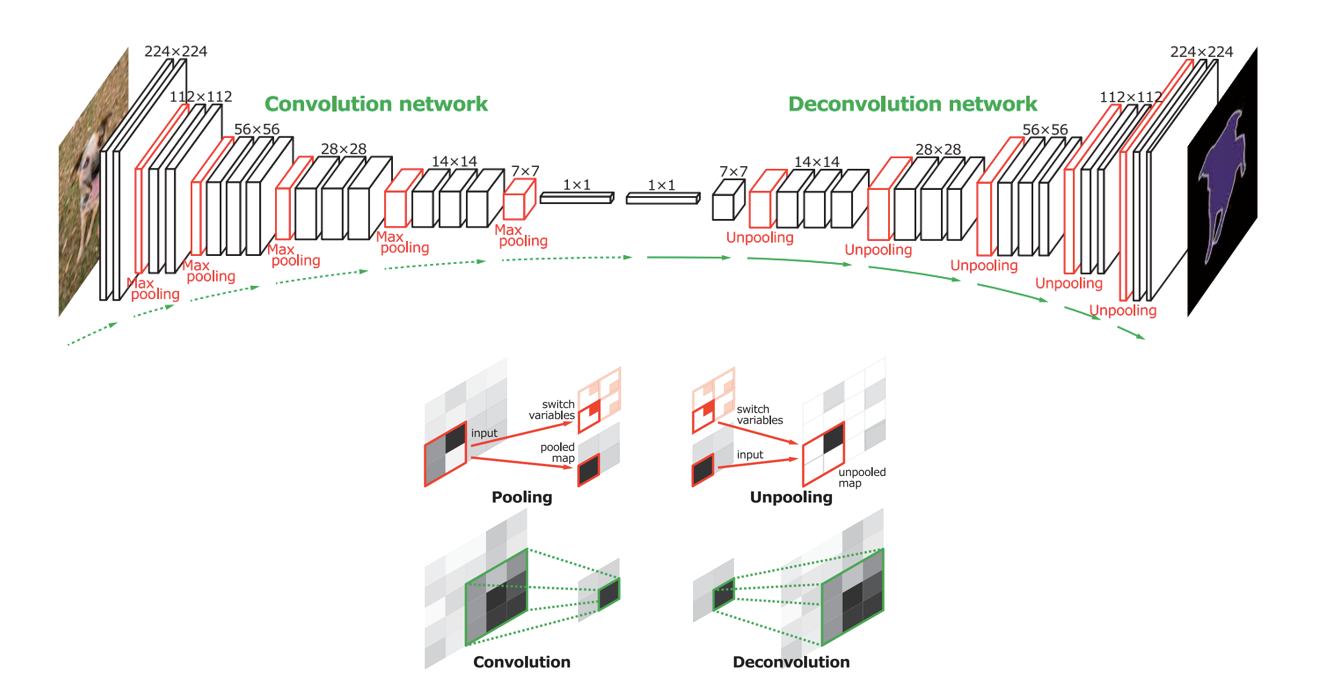

#### DeconvNet

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

_How the information about location is encoded in the network?_

|

||||

|

||||

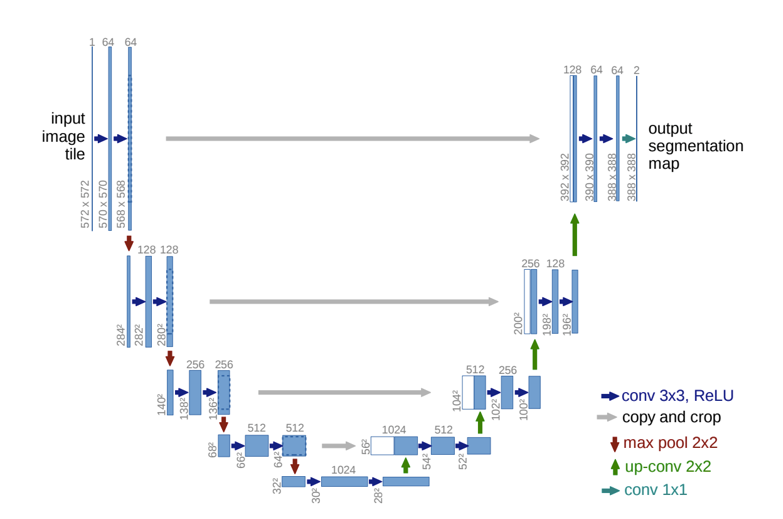

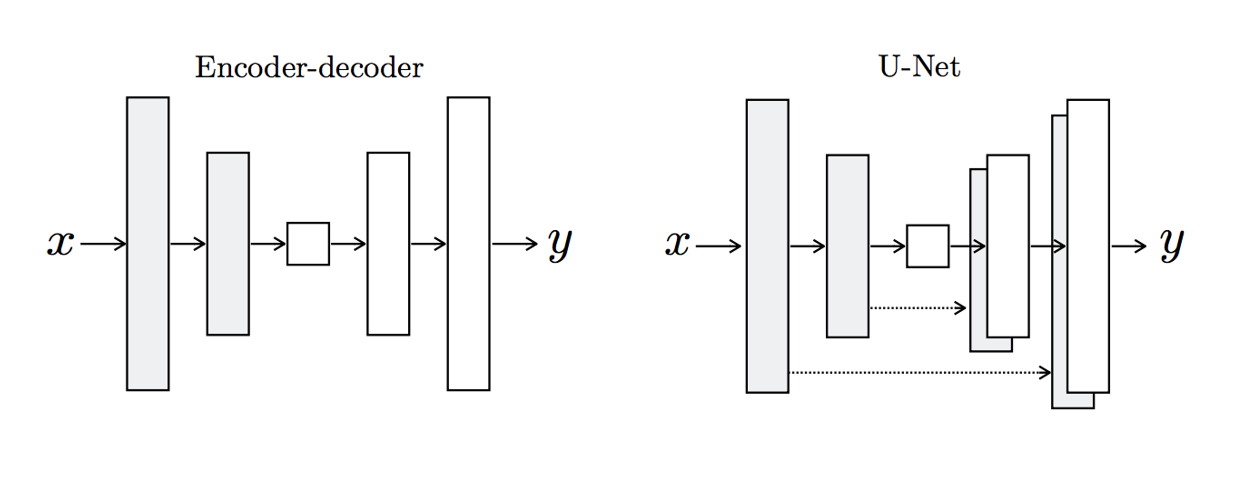

#### U-Net

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

- Like FCN, fuse upsampled higher-level feature maps with higher-res, lower-level feature maps (like residual connections)

|

||||

- Unlike FCN, fuse by concatenation, predict at the end

|

||||

|

||||

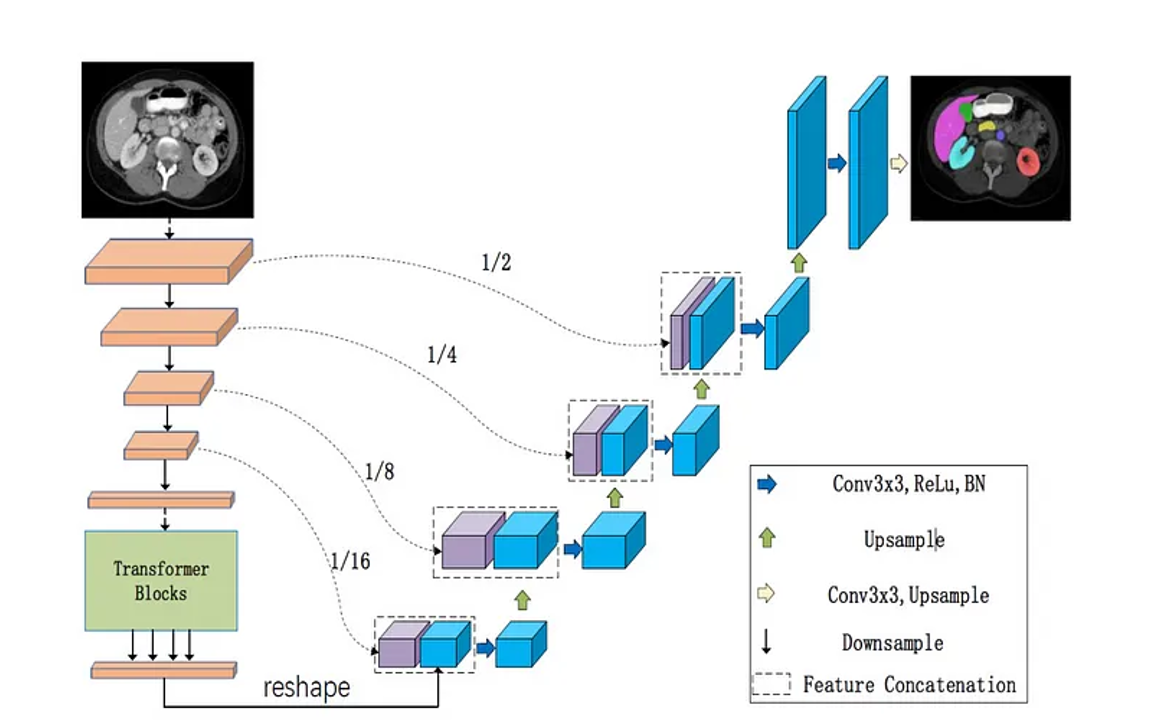

#### Extended U-Net Architecture

|

||||

|

||||

Many variants of U-Net would replace the "encoder" of the U-Net with other architectures.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

##### Encoder/Decoder v.s. U-Net

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

### Instance Segmentation

|

||||

|

||||

#### Mask R-CNN

|

||||

|

||||

Mask R-CNN = Faster R-CNN + FCN on Region of Interest

|

||||

|

||||

### Extend to keypoint prediction?

|

||||

|

||||

- Use a similar architecture to Mask R-CNN

|

||||

|

||||

_Continue on Tuesday_

|

||||

|

||||

### Other tasks

|

||||

|

||||

#### Panoptic feature pyramid network

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

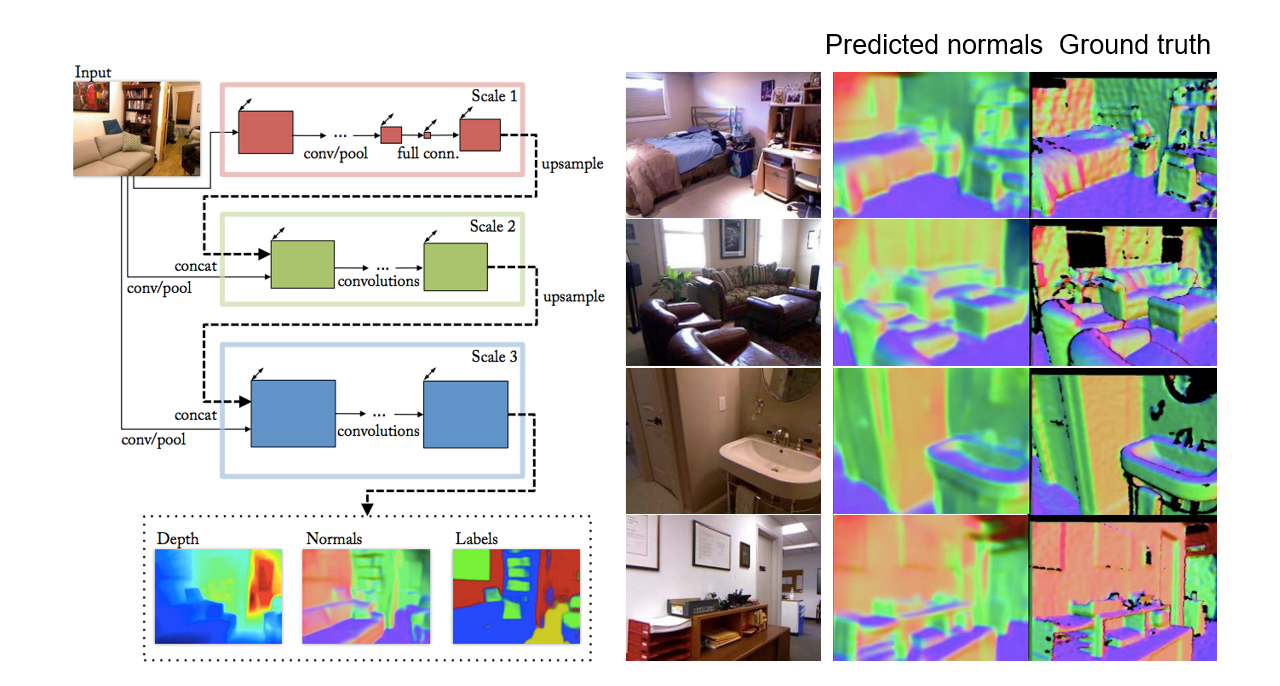

#### Depth and normal estimation

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

D. Eigen and R. Fergus, Predicting Depth, Surface Normals and Semantic Labels with a Common Multi-Scale Convolutional Architecture, ICCV 2015

|

||||

|

||||

#### Colorization

|

||||

|

||||

R. Zhang, P. Isola, and A. Efros, Colorful Image Colorization, ECCV 2016

|

||||

184

content/CSE559A/CSE559A_L17.md

Normal file

184

content/CSE559A/CSE559A_L17.md

Normal file

@@ -0,0 +1,184 @@

|

||||

# CSE559A Lecture 17

|

||||

|

||||

## Local Features

|

||||

|

||||

### Types of local features

|

||||

|

||||

#### Edge

|

||||

|

||||

Goal: Identify sudden changes in image intensity

|

||||

|

||||

Generate edge map as human artists.

|

||||

|

||||

An edge is a place of rapid change in the image intensity function.

|

||||

|

||||

Take the absolute value of the first derivative of the image intensity function.

|

||||

|

||||

For 2d functions, $\frac{\partial f}{\partial x}=\lim_{\Delta x\to 0}\frac{f(x+\Delta x)-f(x)}{\Delta x}$

|

||||

|

||||

For discrete images data, $\frac{\partial f}{\partial x}\approx \frac{f(x+1)-f(x)}{1}$

|

||||

|

||||

Run convolution with kernel $[1,0,-1]$ to get the first derivative in the x direction, without shifting. (generic kernel is $[1,-1]$)

|

||||

|

||||

Prewitt operator:

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

M_x=\begin{bmatrix}

|

||||

1 & 0 & -1 \\

|

||||

1 & 0 & -1 \\

|

||||

1 & 0 & -1 \\

|

||||

\end{bmatrix}

|

||||

\quad

|

||||

M_y=\begin{bmatrix}

|

||||

1 & 1 & 1 \\

|

||||

0 & 0 & 0 \\

|

||||

-1 & -1 & -1 \\

|

||||

\end{bmatrix}

|

||||

$$

|

||||

Sobel operator:

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

M_x=\begin{bmatrix}

|

||||

1 & 0 & -1 \\

|

||||

2 & 0 & -2 \\

|

||||

1 & 0 & -1 \\

|

||||

\end{bmatrix}

|

||||

\quad

|

||||

M_y=\begin{bmatrix}

|

||||

1 & 2 & 1 \\

|

||||

0 & 0 & 0 \\

|

||||

-1 & -2 & -1 \\

|

||||

\end{bmatrix}

|

||||

$$

|

||||

Roberts operator:

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

M_x=\begin{bmatrix}

|

||||

1 & 0 \\

|

||||

0 & -1 \\

|

||||

\end{bmatrix}

|

||||

\quad

|

||||

M_y=\begin{bmatrix}

|

||||

0 & 1 \\

|

||||

-1 & 0 \\

|

||||

\end{bmatrix}

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

Image gradient:

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\nabla f = \left(\frac{\partial f}{\partial x}, \frac{\partial f}{\partial y}\right)

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

Gradient magnitude:

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

||\nabla f|| = \sqrt{\left(\frac{\partial f}{\partial x}\right)^2 + \left(\frac{\partial f}{\partial y}\right)^2}

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

Gradient direction:

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\theta = \tan^{-1}\left(\frac{\frac{\partial f}{\partial y}}{\frac{\partial f}{\partial x}}\right)

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

The gradient points in the direction of the most rapid increase in intensity.

|

||||

|

||||

> Application: Gradient-domain image editing

|

||||

>

|

||||

> Goal: solve for pixel values in the target region to match gradients of the source region while keeping the rest of the image unchanged.

|

||||

>

|

||||

> [Poisson Image Editing](http://www.cs.virginia.edu/~connelly/class/2014/comp_photo/proj2/poisson.pdf)

|

||||

|

||||

Noisy edge detection:

|

||||

|

||||

When the intensity function is very noisy, we can use a Gaussian smoothing filter to reduce the noise before taking the gradient.

|

||||

|

||||

Suppose pixels of the true image $f_{i,j}$ are corrupted by Gaussian noise $n_{i,j}$ with mean 0 and variance $\sigma^2$.

|

||||

Then the noisy image is $g_{i,j}=(f_{i,j}+n_{i,j})-(f_{i,j+1}+n_{i,j+1})\approx N(0,2\sigma^2)$

|

||||

|

||||

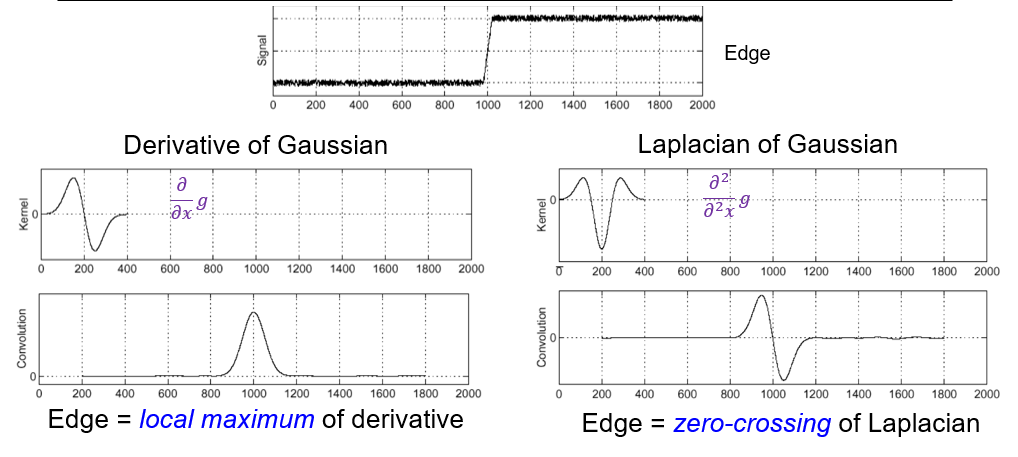

To find edges, look for peaks in $\frac{d}{dx}(f\circ g)$ where $g$ is the Gaussian smoothing filter.

|

||||

|

||||

or we can directly use the Derivative of Gaussian (DoG) filter:

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\frac{d}{dx}g(x,\sigma)=\frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi\sigma^2}}e^{-\frac{x^2}{2\sigma^2}}

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

##### Separability of Gaussian filter

|

||||

|

||||

A Gaussian filter is separable if it can be written as a product of two 1D filters.

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\frac{d}{dx}g(x,\sigma)=\frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi\sigma^2}}e^{-\frac{x^2}{2\sigma^2}}

|

||||

\quad \frac{d}{dy}g(y,\sigma)=\frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi\sigma^2}}e^{-\frac{y^2}{2\sigma^2}}

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

##### Separable Derivative of Gaussian (DoG) filter

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\frac{d}{dx}g(x,y)\propto -x\exp\left(-\frac{x^2+y^2}{2\sigma^2}\right)

|

||||

\quad \frac{d}{dy}g(x,y)\propto -y\exp\left(-\frac{x^2+y^2}{2\sigma^2}\right)

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

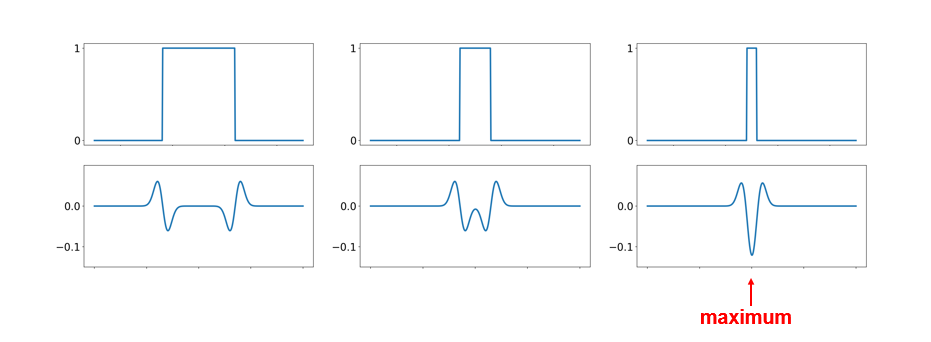

##### Derivative of Gaussian: Scale

|

||||

|

||||

Using Gaussian derivatives with different values of 𝜎 finds structures at different scales or frequencies

|

||||

|

||||

(Take the hybrid image as an example)

|

||||

|

||||

##### Canny edge detector

|

||||

|

||||

1. Smooth the image with a Gaussian filter

|

||||

2. Compute the gradient magnitude and direction of the smoothed image

|

||||

3. Thresholding gradient magnitude

|

||||

4. Non-maxima suppression

|

||||

- For each location `q` above the threshold, check that the gradient magnitude is higher than at adjacent points `p` and `r` in the direction of the gradient

|

||||

5. Thresholding the non-maxima suppressed gradient magnitude

|

||||

6. Hysteresis thresholding

|

||||

- Use two thresholds: high and low

|

||||

- Start with a seed edge pixel with a gradient magnitude greater than the high threshold

|

||||

- Follow the gradient direction to find all connected pixels with a gradient magnitude greater than the low threshold

|

||||

|

||||

##### Top-down segmentation

|

||||

|

||||

Data-driven top-down segmentation:

|

||||

|

||||

#### Interest point

|

||||

|

||||

Key point matching:

|

||||

|

||||

1. Find a set of distinctive keypoints in the image

|

||||

2. Define a region of interest around each keypoint

|

||||

3. Compute a local descriptor from the normalized region

|

||||

4. Match local descriptors between images

|

||||

|

||||

Characteristic of good features:

|

||||

|

||||

- Repeatability

|

||||

- The same feature can be found in several images despite geometric and photometric transformations

|

||||

- Saliency

|

||||

- Each feature is distinctive

|

||||

- Compactness and efficiency

|

||||

- Many fewer features than image pixels

|

||||

- Locality

|

||||

- A feature occupies a relatively small area of the image; robust to clutter and occlusion

|

||||

|

||||

##### Harris corner detector

|

||||

|

||||

### Applications of local features

|

||||

|

||||

#### Image alignment

|

||||

|

||||

#### 3D reconstruction

|

||||

|

||||

#### Motion tracking

|

||||

|

||||

#### Robot navigation

|

||||

|

||||

#### Indexing and database retrieval

|

||||

|

||||

#### Object recognition

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

68

content/CSE559A/CSE559A_L18.md

Normal file

68

content/CSE559A/CSE559A_L18.md

Normal file

@@ -0,0 +1,68 @@

|

||||

# CSE559A Lecture 18

|

||||

|

||||

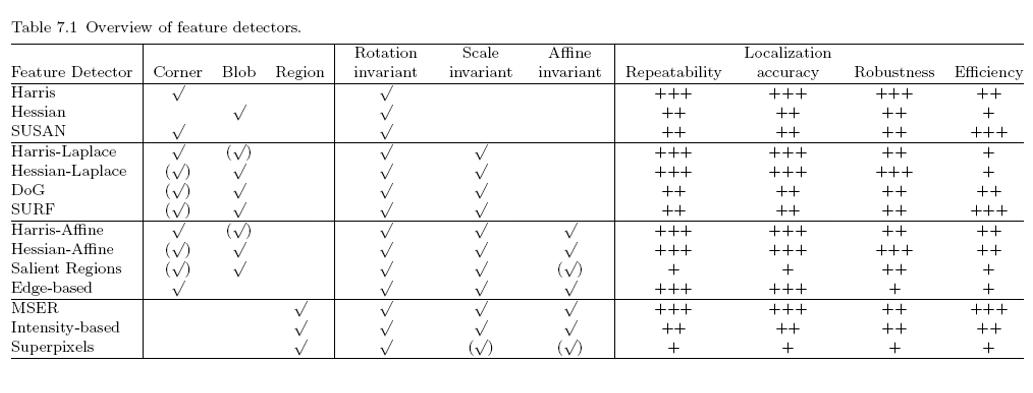

## Continue on Harris Corner Detector

|

||||

|

||||

Goal: Descriptor distinctiveness

|

||||

|

||||

- We want to be able to reliably determine which point goes with which.

|

||||

- Must provide some invariance to geometric and photometric differences.

|

||||

|

||||

Harris corner detector:

|

||||

|

||||

> Other existing variants:

|

||||

> - Hessian & Harris: [Beaudet '78], [Harris '88]

|

||||

> - Laplacian, DoG: [Lindeberg '98], [Lowe 1999]

|

||||

> - Harris-/Hessian-Laplace: [Mikolajczyk & Schmid '01]

|

||||

> - Harris-/Hessian-Affine: [Mikolajczyk & Schmid '04]

|

||||

> - EBR and IBR: [Tuytelaars & Van Gool '04]

|

||||

> - MSER: [Matas '02]

|

||||

> - Salient Regions: [Kadir & Brady '01]

|

||||

> - Others…

|

||||

|

||||

### Deriving a corner detection criterion

|

||||

|

||||

- Basic idea: we should easily recognize the point by looking through a small window

|

||||

- Shifting a window in any direction should give a large change in intensity

|

||||

|

||||

Corner is the point where the intensity changes in all directions.

|

||||

|

||||

Criterion:

|

||||

|

||||

Change in appearance of window $W$ for the shift $(u,v)$:

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

E(u,v) = \sum_{x,y\in W} [I(x+u,y+v) - I(x,y)]^2

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

First-order Taylor approximation for small shifts $(u,v)$:

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

I(x+u,y+v) \approx I(x,y) + I_x u + I_y v

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

plug into $E(u,v)$:

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\begin{aligned}

|

||||

E(u,v) &= \sum_{(x,y)\in W} [I(x+u,y+v) - I(x,y)]^2 \\

|

||||

&\approx \sum_{(x,y)\in W} [I(x,y) + I_x u + I_y v - I(x,y)]^2 \\

|

||||

&= \sum_{(x,y)\in W} [I_x u + I_y v]^2 \\

|

||||

&= \sum_{(x,y)\in W} [I_x^2 u^2 + 2 I_x I_y u v + I_y^2 v^2]

|

||||

\end{aligned}

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

Consider the second moment matrix:

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

M = \begin{bmatrix}

|

||||

I_x^2 & I_x I_y \\

|

||||

I_x I_y & I_y^2

|

||||

\end{bmatrix}=\begin{bmatrix}

|

||||

a & 0 \\

|

||||

0 & b

|

||||

\end{bmatrix}

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

If either $a$ or $b$ is small, then the window is not a corner.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

71

content/CSE559A/CSE559A_L19.md

Normal file

71

content/CSE559A/CSE559A_L19.md

Normal file

@@ -0,0 +1,71 @@

|

||||

# CSE559A Lecture 19

|

||||

|

||||

## Feature Detection

|

||||

|

||||

### Behavior of corner features with respect to Image Transformations

|

||||

|

||||

To be useful for image matching, “the same” corner features need to show up despite geometric and photometric transformations

|

||||

|

||||

We need to analyze how the corner response function and the corner locations change in response to various transformations

|

||||

|

||||

#### Affine intensity change

|

||||

|

||||

Solution:

|

||||

|

||||

- Only derivative of intensity are used (invariant to intensity change)

|

||||

- Intensity scaling

|

||||

|

||||

#### Image translation

|

||||

|

||||

Solution:

|

||||

|

||||

- Derivatives and window function are shift invariant

|

||||

|

||||

#### Image rotation

|

||||

|

||||

Second moment ellipse rotates but its shape (i.e. eigenvalues) remains the same

|

||||

|

||||

#### Scaling

|

||||

|

||||

Classify edges instead of corners

|

||||

|

||||

## Automatic Scale selection for interest point detection

|

||||

|

||||

### Scale space

|

||||

|

||||

We want to extract keypoints with characteristic scales that are equivariant (or covariant) with respect to scaling of the image

|

||||

|

||||

Approach: compute a scale-invariant response function over neighborhoods centered at each location $(x,y)$ and a range of scales $\sigma$, find scale-space locations $(x,y,\sigma)$ where this function reaches a local maximum

|

||||

|

||||

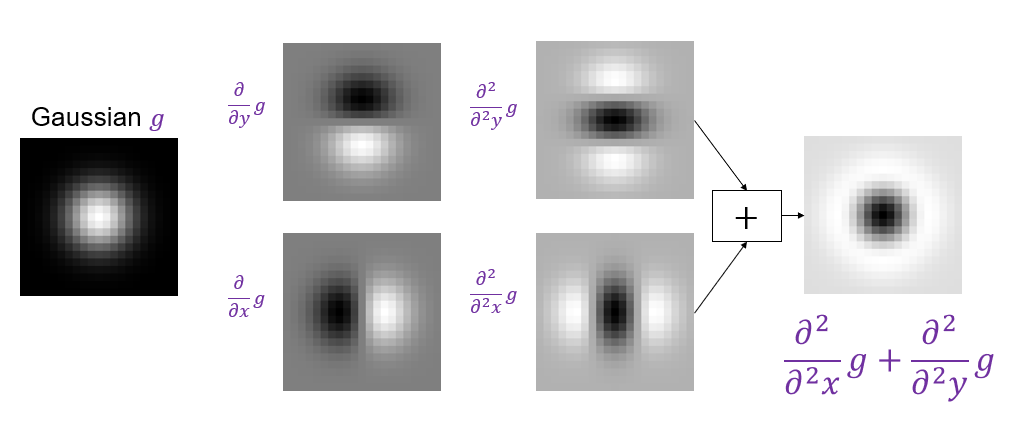

A particularly convenient response function is given by the scale-normalized Laplacian of Gaussian (LoG) filter:

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\nabla^2_{norm}=\sigma^2\nabla^2\left(\frac{\partial^2}{\partial x^2}g+\frac{\partial^2}{\partial y^2}g\right)

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

#### Edge detection with LoG

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

#### Blob detection with LoG

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

### Difference of Gaussians (DoG)

|

||||

|

||||

DoG has a little more flexibility, since you can select the scales of the Gaussians.

|

||||

|

||||

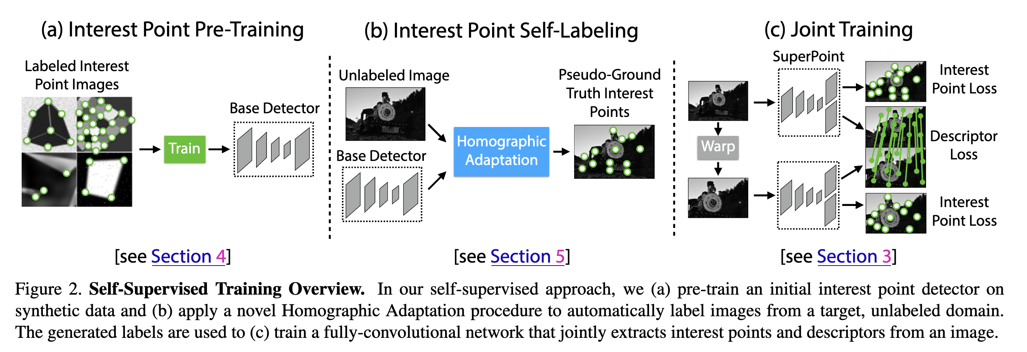

### Scale-invariant feature transform (SIFT)

|

||||

|

||||

The main goal of SIFT is to enable image matching in the presence of significant transformations

|

||||

|

||||

- To recognize the same keypoint in multiple images, we need to match appearance descriptors or "signatures" in their neighborhoods

|

||||

- Descriptors that are locally invariant w.r.t. scale and rotation can handle a wide range of global transformations

|

||||

|

||||

### Maximum stable extremal regions (MSER)

|

||||

|

||||

Based on Watershed segmentation algorithm

|

||||

|

||||

Select regions that are stable over a large parameter range

|

||||

165

content/CSE559A/CSE559A_L2.md

Normal file

165

content/CSE559A/CSE559A_L2.md

Normal file

@@ -0,0 +1,165 @@

|

||||

# CSE559A Lecture 2

|

||||

|

||||

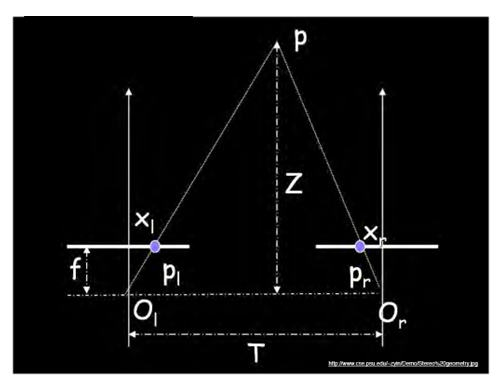

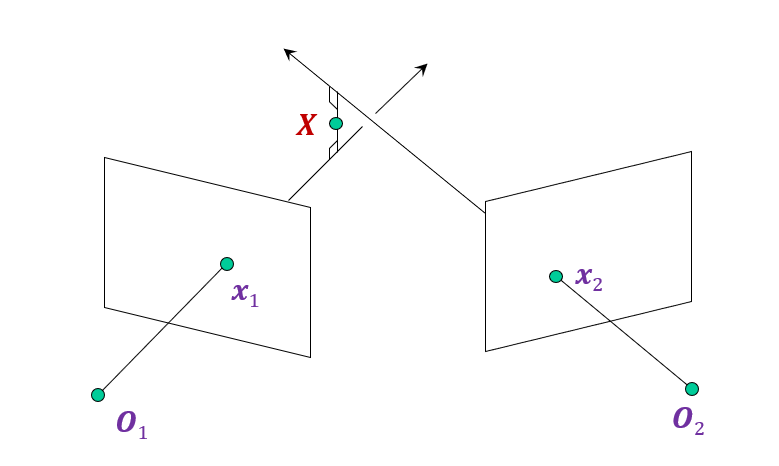

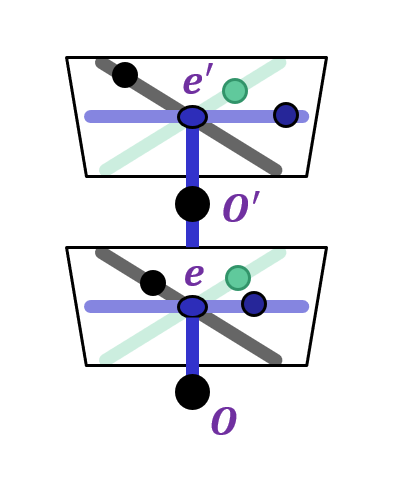

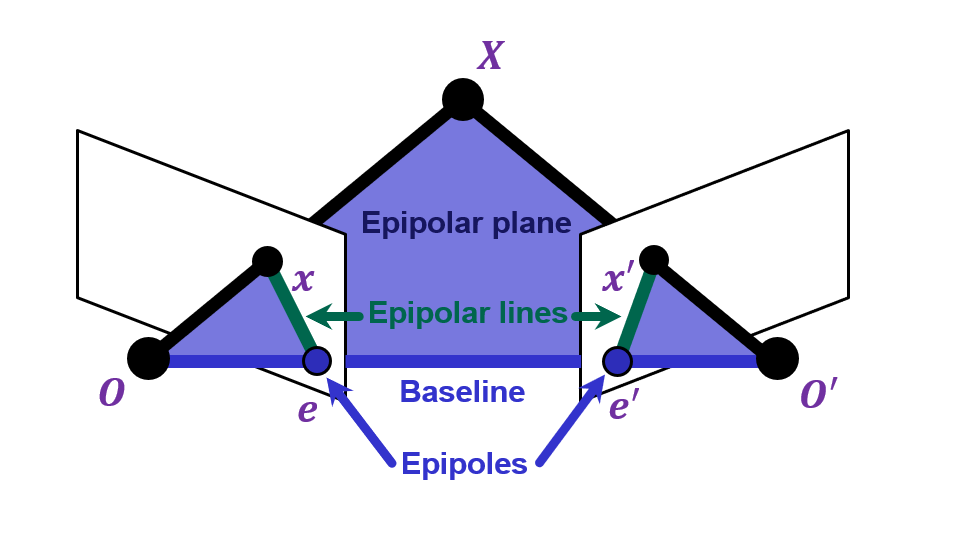

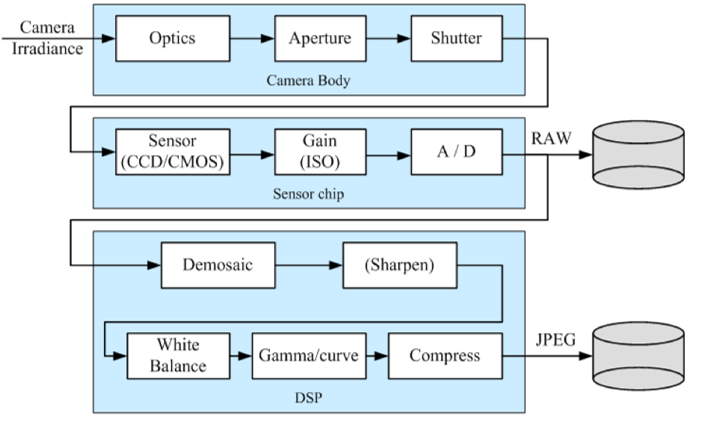

## The Geometry of Image Formation

|

||||

|

||||

Mapping between image and world coordinates.

|

||||

|

||||

Today's focus:

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

x=K[R\ t]X

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

### Pinhole Camera Model

|

||||

|

||||

Add a barrier to block off most of the rays.

|

||||

|

||||

- Reduce blurring

|

||||

- The opening known as the **aperture**

|

||||

|

||||

$f$ is the focal length.

|

||||

$c$ is the center of the aperture.

|

||||

|

||||

#### Focal length/ Field of View (FOV)/ Zoom

|

||||

|

||||

- Focal length: distance between the aperture and the image plane.

|

||||

- Field of View (FOV): the angle between the two rays that pass through the aperture and the image plane.

|

||||

- Zoom: the ratio of the focal length to the image plane.

|

||||

|

||||

#### Other types of projection

|

||||

|

||||

Beyond the pinhole/perspective camera model, there are other types of projection.

|

||||

|

||||

- Radial distortion

|

||||

- 360-degree camera

|

||||

- Equirectangular Panoramas

|

||||

- Random lens

|

||||

- Rotating sensors

|

||||

- Photofinishing

|

||||

- Tiltshift lens

|

||||

|

||||

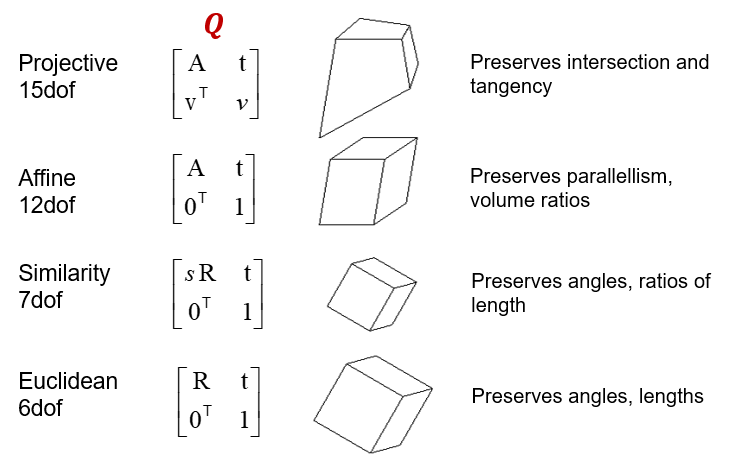

### Perspective Geometry

|

||||

|

||||

Length and area are not preserved.

|

||||

|

||||

Angle is not preserved.

|

||||

|

||||

But straight lines are still straight.

|

||||

|

||||

Parallel lines in the world intersect at a **vanishing point** on the image plane.

|

||||

|

||||

Vanishing lines: the set of all vanishing points of parallel lines in the world on the same plane in the world.

|

||||

|

||||

Vertical vanishing point at infinity.

|

||||

|

||||

### Camera/Projection Matrix

|

||||

|

||||

Linear projection model.

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

x=K[R\ t]X

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

- $x$: image coordinates 2d (homogeneous coordinates)

|

||||

- $X$: world coordinates 3d (homogeneous coordinates)

|

||||

- $K$: camera matrix (3x3 and invertible)

|

||||

- $R$: camera rotation matrix (3x3)

|

||||

- $t$: camera translation vector (3x1)

|

||||

|

||||

#### Homogeneous coordinates

|

||||

|

||||

- 2D: $$(x, y)\to\begin{bmatrix}x\\y\\1\end{bmatrix}$$

|

||||

- 3D: $$(x, y, z)\to\begin{bmatrix}x\\y\\z\\1\end{bmatrix}$$

|

||||

|

||||

converting from homogeneous to inhomogeneous coordinates:

|

||||

|

||||

- 2D: $$\begin{bmatrix}x\\y\\w\end{bmatrix}\to(x/w, y/w)$$

|

||||

- 3D: $$\begin{bmatrix}x\\y\\z\\w\end{bmatrix}\to(x/w, y/w, z/w)$$

|

||||

|

||||

When $w=0$, the point is at infinity.

|

||||

|

||||

Homogeneous coordinates are invariant under scaling (non-zero scalar).

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

k\begin{bmatrix}x\\y\\w\end{bmatrix}=\begin{bmatrix}kx\\ky\\kw\end{bmatrix}\implies\begin{bmatrix}x\\y\end{bmatrix}=\begin{bmatrix}x/k\\y/k\end{bmatrix}

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

A convenient way to represent a point at infinity is to use a unit vector.

|

||||

|

||||

Line equation: $ax+by+c=0$

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

line_i=\begin{bmatrix}a_i\\b_i\\c_i\end{bmatrix}

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

Append a 1 to pixel coordinates to get homogeneous coordinates.

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

pixel_i=\begin{bmatrix}u_i\\v_i\\1\end{bmatrix}

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

Line given by cross product of two points:

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

line_i=pixel_1\times pixel_2

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

Intersection of two lines given by cross product of the lines:

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

pixel_i=line_1\times line_2

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

#### Pinhole Camera Projection Matrix

|

||||

|

||||

Intrinsic Assumptions:

|

||||

|

||||

- Unit aspect ratio

|

||||

- No skew

|

||||

- Optical center at (0,0)

|

||||

|

||||

Extrinsic Assumptions:

|

||||

|

||||

- No rotation

|

||||

- No translation (camera at world origin)

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

x=K[I\ 0]X\implies w\begin{bmatrix}u\\v\\1\end{bmatrix}=\begin{bmatrix}f&0&0&0\\0&f&0&0\\0&0&1&0\end{bmatrix}\begin{bmatrix}x\\y\\z\\1\end{bmatrix}

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

Removing the assumptions:

|

||||

|

||||

Intrinsic assumptions:

|

||||

|

||||

- Unit aspect ratio

|

||||

- No skew

|

||||

|

||||

Extrinsic assumptions:

|

||||

|

||||

- No rotation

|

||||

- No translation

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

x=K[I\ 0]X\implies w\begin{bmatrix}u\\v\\1\end{bmatrix}=\begin{bmatrix}\alpha&0&u_0&0\\0&\beta&v_0&0\\0&0&1&0\end{bmatrix}\begin{bmatrix}x\\y\\z\\1\end{bmatrix}

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

Adding skew:

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

x=K[I\ 0]X\implies w\begin{bmatrix}u\\v\\1\end{bmatrix}=\begin{bmatrix}\alpha&s&u_0&0\\0&\beta&v_0&0\\0&0&1&0\end{bmatrix}\begin{bmatrix}x\\y\\z\\1\end{bmatrix}

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

Finally, adding camera rotation and translation:

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

x=K[I\ t]X\implies w\begin{bmatrix}u\\v\\1\end{bmatrix}=\begin{bmatrix}\alpha&s&u_0\\0&\beta&v_0\\0&0&1\end{bmatrix}\begin{bmatrix}r_{11}&r_{12}&r_{13}&t_x\\r_{21}&r_{22}&r_{23}&t_y\\r_{31}&r_{32}&r_{33}&t_z\end{bmatrix}\begin{bmatrix}x\\y\\z\\1\end{bmatrix}

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

What is the degrees of freedom of the camera matrix?

|

||||

|

||||

- rotation: 3

|

||||

- translation: 3

|

||||

- camera matrix: 5

|

||||

|

||||

Total: 11

|

||||

145

content/CSE559A/CSE559A_L20.md

Normal file

145

content/CSE559A/CSE559A_L20.md

Normal file

@@ -0,0 +1,145 @@

|

||||

# CSE559A Lecture 20

|

||||

|

||||

## Local feature descriptors

|

||||

|

||||

Detection: Identify the interest points

|

||||

|

||||

Description: Extract vector feature descriptor surrounding each interest point.

|

||||

|

||||

Matching: Determine correspondence between descriptors in two views

|

||||

|

||||

### Image representation

|

||||

|

||||

Histogram of oriented gradients (HOG)

|

||||

|

||||

- Quantization

|

||||

- Grids: fast but applicable only with few dimensions

|

||||

- Clustering: slower but can quantize data in higher dimensions

|

||||

- Matching

|

||||

- Histogram intersection or Euclidean may be faster

|

||||

- Chi-squared often works better

|

||||

- Earth mover’s distance is good for when nearby bins represent similar values

|

||||

|

||||

#### SIFT vector formation

|

||||

|

||||

Computed on rotated and scaled version of window according to computed orientation & scale

|

||||

|

||||

- resample the window

|

||||

|

||||

Based on gradients weighted by a Gaussian of variance half the window (for smooth falloff)

|

||||

|

||||

4x4 array of gradient orientation histogram weighted by magnitude

|

||||

|

||||

8 orientations x 4x4 array = 128 dimensions

|

||||

|

||||

Motivation: some sensitivity to spatial layout, but not too much.

|

||||

|

||||

For matching:

|

||||

|

||||

- Extraordinarily robust detection and description technique

|

||||

- Can handle changes in viewpoint

|

||||

- Up to about 60 degree out-of-plane rotation

|

||||

- Can handle significant changes in illumination

|

||||

- Sometimes even day vs. night

|

||||

- Fast and efficient—can run in real time

|

||||

- Lots of code available

|

||||

|

||||

#### SURF

|

||||

|

||||

- Fast approximation of SIFT idea

|

||||

- Efficient computation by 2D box filters & integral images

|

||||

- 6 times faster than SIFT

|

||||

- Equivalent quality for object identification

|

||||

|

||||

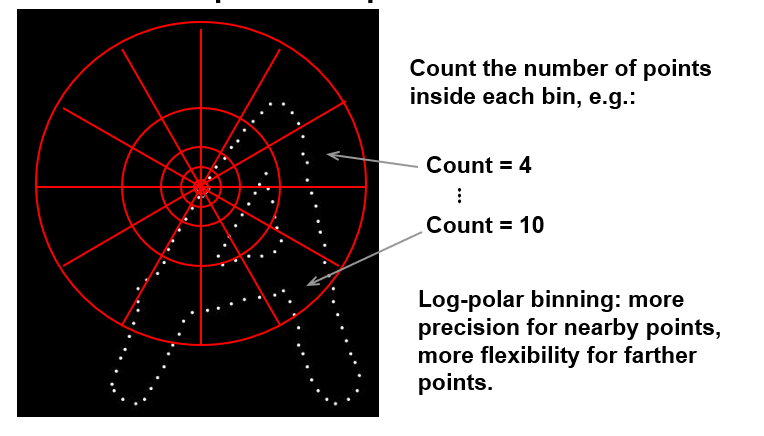

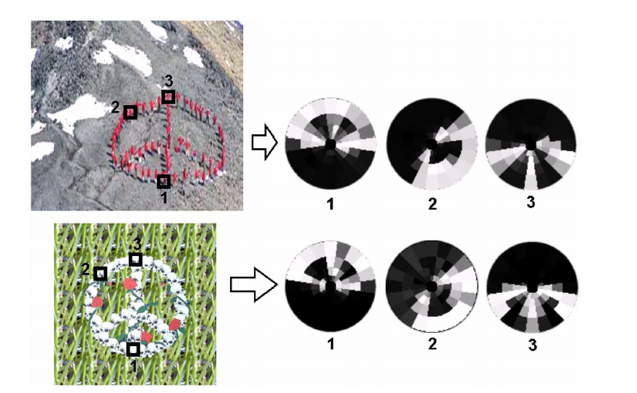

#### Shape context

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

#### Self-similarity Descriptor

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

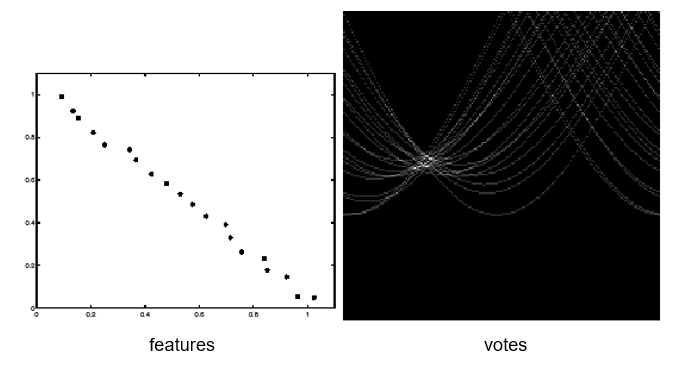

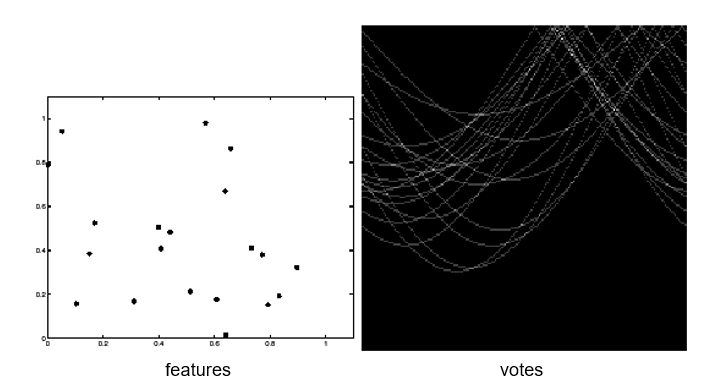

## Local feature matching

|

||||

|

||||

### Matching

|

||||

|

||||

Simplest approach: Pick the nearest neighbor. Threshold on absolute distance

|

||||

|

||||

Problem: Lots of self similarity in many photos

|

||||

|

||||

Solution: Nearest neighbor with low ratio test

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

## Deep Learning for Correspondence Estimation

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

## Optical Flow

|

||||

|

||||

### Field

|

||||

|

||||

Motion field: the projection of the 3D scene motion into the image

|

||||

Magnitude of vectors is determined by metric motion

|

||||

Only caused by motion

|

||||

|

||||

Optical flow: the apparent motion of brightness patterns in the image

|

||||

Magnitude of vectors is measured in pixels

|

||||

Can be caused by lightning

|

||||

|

||||

### Brightness constancy constraint, aperture problem

|

||||

|

||||

Machine Learning Approach

|

||||

|

||||

- Collect examples of inputs and outputs

|

||||

- Design a prediction model suitable for the task

|

||||

- Invariances, Equivariances; Complexity; Input and Output shapes and semantics

|

||||

- Specify loss functions and train model

|

||||

- Limitations: Requires training the model; Requires a sufficiently complete training dataset; Must re-learn known facts; Higher computational complexity

|

||||

|

||||

Optimization Approach

|

||||

|

||||

- Define properties we expect to hold for a correct solution

|

||||

- Translate properties into a cost function

|

||||

- Derive an algorithm to solve for the cost function

|

||||

- Limitations: Often requires making overly simple assumptions on properties; Some tasks can’t be easily defined

|

||||

|

||||

Given frames at times $t-1$ and $t$, estimate the apparent motion field $u(x,y)$ and $v(x,y)$ between them

|

||||

Brightness constancy constraint: projection of the same point looks the same in every frame

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

I(x,y,t-1) = I(x+u(x,y),y+v(x,y),t)

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

Additional assumptions:

|

||||

|

||||

- Small motion: points do not move very far

|

||||

- Spatial coherence: points move like their neighbors

|

||||

|

||||

Trick for solving:

|

||||

|

||||

Brightness constancy constraint:

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

I(x,y,t-1) = I(x+u(x,y),y+v(x,y),t)

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

Linearize the right-hand side using Taylor expansion:

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

I(x,y,t-1) \approx I(x,y,t) + I_x u(x,y) + I_y v(x,y)

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

I_x u(x,y) + I_y v(x,y) + I(x,y,t) - I(x,y,t-1) = 0

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

Hence,

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

I_x u(x,y) + I_y v(x,y) + I_t = 0

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

215

content/CSE559A/CSE559A_L21.md

Normal file

215

content/CSE559A/CSE559A_L21.md

Normal file

@@ -0,0 +1,215 @@

|

||||

# CSE559A Lecture 21

|

||||

|

||||

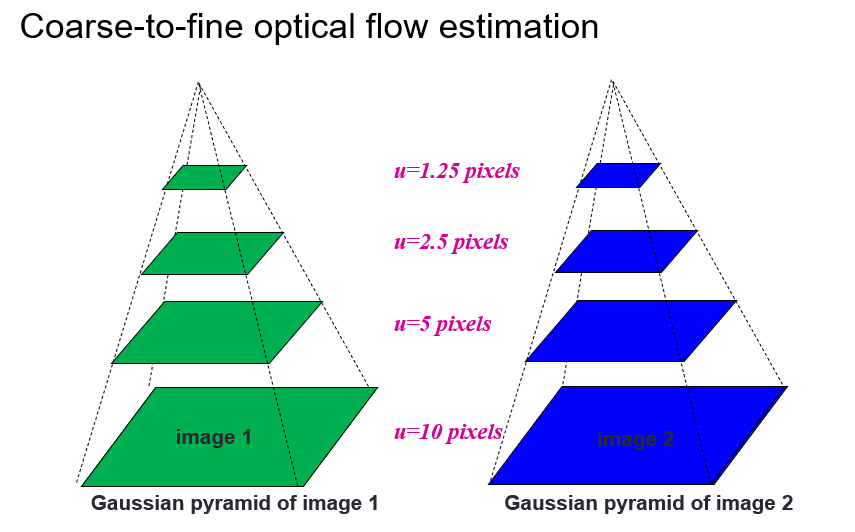

## Continue on optical flow

|

||||

|

||||

### The brightness constancy constraint

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

I_x u(x,y) + I_y v(x,y) + I_t = 0

|

||||

$$

|

||||

Given the gradients $I_x, I_y$ and $I_t$, can we uniquely recover the motion $(u,v)$?

|

||||

|

||||

- Suppose $(u, v)$ satisfies the constraint: $\nabla I \cdot (u,v) + I_t = 0$

|

||||

- Then $\nabla I \cdot (u+u', v+v') + I_t = 0$ for any $(u', v')$ s.t. $\nabla I \cdot (u', v') = 0$

|

||||