Compare commits

88 Commits

| Author | SHA1 | Date | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

7abc8d7e80 | ||

|

|

c42e7e6489 | ||

|

|

6966db6478 | ||

|

|

0b736aa18d | ||

|

|

726c6a4851 | ||

|

|

7d8196635e | ||

|

|

55decba076 | ||

|

|

12ae242e90 | ||

|

|

1f55c5c06d | ||

|

|

afaf1e2cc3 | ||

|

|

3393ce74ba | ||

|

|

8120c0172f | ||

|

|

681dcd2aed | ||

|

|

65a0506487 | ||

|

|

df2425b79b | ||

|

|

4ccde07071 | ||

|

|

2a094032b7 | ||

|

|

34182ff139 | ||

|

|

3242bfc299 | ||

|

|

fbae7a7d00 | ||

|

|

6fe30d7965 | ||

|

|

d9bd0a926d | ||

|

|

1c54bf0b26 | ||

|

|

8b579a7873 | ||

|

|

0512c48967 | ||

|

|

56e93bb007 | ||

|

|

000922f9bd | ||

|

|

87f31f5c7f | ||

|

|

970ee8fa5a | ||

|

|

d90faea29b | ||

|

|

1fac4c46fa | ||

|

|

5e4a3cec08 | ||

|

|

8e73cf3205 | ||

|

|

978430adca | ||

|

|

2946feefbe | ||

|

|

9416bd4956 | ||

|

|

946d0b605f | ||

|

|

8bc6524b82 | ||

|

|

52a152f827 | ||

|

|

5c342e4008 | ||

|

|

4c715753b2 | ||

|

|

0597afb511 | ||

|

|

1b75ef050f | ||

|

|

8d4e078460 | ||

|

|

34afc00a7f | ||

|

|

51c9f091d6 | ||

|

|

2d16f19411 | ||

|

|

7cf48b98ae | ||

|

|

d4f0bdc7f4 | ||

|

|

6a7fbc6de1 | ||

|

|

c426033b63 | ||

|

|

74364283fe | ||

|

|

51b34be077 | ||

|

|

5c8a3b27c0 | ||

|

|

76c2588e46 | ||

|

|

2c5f1b98ca | ||

|

|

1d662e1f32 | ||

|

|

b28f6c5d9f | ||

|

|

614479e4d0 | ||

|

|

d24c0bdd9e | ||

|

|

71ada8d498 | ||

|

|

bc44c59707 | ||

|

|

d45e219fa4 | ||

|

|

a86f298001 | ||

|

|

91f8359a5a | ||

|

|

a9d84cb2bb | ||

|

|

f13b49aa92 | ||

|

|

9a9ca265ec | ||

|

|

22ee558393 | ||

|

|

6276125e54 | ||

|

|

aa8dee67d9 | ||

|

|

e7abef9e14 | ||

|

|

d3a65fd283 | ||

|

|

78d6decd10 | ||

|

|

52c14c5448 | ||

|

|

4b77a1e8e4 | ||

|

|

47a27d1987 | ||

|

|

361745d658 | ||

|

|

e4490f6fa2 | ||

|

|

6acd8adf32 | ||

|

|

5e5a6a2a03 | ||

|

|

1577ddc0d9 | ||

|

|

1476e7f1c2 | ||

|

|

f634254bca | ||

|

|

fb1ffcd040 | ||

|

|

0d93eb43d3 | ||

|

|

a6012a17c1 | ||

|

|

f124f7a744 |

73

.github/workflows/sync-from-gitea.yml

vendored

Normal file

73

.github/workflows/sync-from-gitea.yml

vendored

Normal file

@@ -0,0 +1,73 @@

|

||||

name: Sync from Gitea (main→main, keep workflow)

|

||||

|

||||

on:

|

||||

schedule:

|

||||

# 2 times per day (UTC): 7:00, 11:00

|

||||

- cron: '0 19,23 * * *'

|

||||

workflow_dispatch: {}

|

||||

|

||||

permissions:

|

||||

contents: write # allow pushing with GITHUB_TOKEN

|

||||

|

||||

jobs:

|

||||

mirror:

|

||||

runs-on: ubuntu-latest

|

||||

|

||||

steps:

|

||||

- name: Check out GitHub repo

|

||||

uses: actions/checkout@v4

|

||||

with:

|

||||

fetch-depth: 0

|

||||

|

||||

- name: Fetch from Gitea

|

||||

env:

|

||||

GITEA_URL: ${{ secrets.GITEA_URL }}

|

||||

GITEA_USER: ${{ secrets.GITEA_USERNAME }}

|

||||

GITEA_TOKEN: ${{ secrets.GITEA_TOKEN }}

|

||||

run: |

|

||||

# Build authenticated Gitea URL: https://USER:TOKEN@...

|

||||

AUTH_URL="${GITEA_URL/https:\/\//https:\/\/$GITEA_USER:$GITEA_TOKEN@}"

|

||||

|

||||

git remote add gitea "$AUTH_URL"

|

||||

git fetch gitea --prune

|

||||

|

||||

- name: Update main from gitea/main, keep workflow, and force-push

|

||||

env:

|

||||

GH_TOKEN: ${{ secrets.GITHUB_TOKEN }}

|

||||

GH_REPO: ${{ github.repository }}

|

||||

run: |

|

||||

# Configure identity for commits made by this workflow

|

||||

git config user.name "github-actions[bot]"

|

||||

git config user.email "github-actions[bot]@users.noreply.github.com"

|

||||

|

||||

# Authenticated push URL for GitHub

|

||||

git remote set-url origin "https://x-access-token:${GH_TOKEN}@github.com/${GH_REPO}.git"

|

||||

|

||||

WF_PATH=".github/workflows/sync-from-gitea.yml"

|

||||

|

||||

# If the workflow exists in the current checkout, save a copy

|

||||

if [ -f "$WF_PATH" ]; then

|

||||

mkdir -p /tmp/gh-workflows

|

||||

cp "$WF_PATH" /tmp/gh-workflows/

|

||||

fi

|

||||

|

||||

# Reset local 'main' to exactly match gitea/main

|

||||

if git show-ref --verify --quiet refs/remotes/gitea/main; then

|

||||

git checkout -B main gitea/main

|

||||

else

|

||||

echo "No gitea/main found, nothing to sync."

|

||||

exit 0

|

||||

fi

|

||||

|

||||

# Restore the workflow into the new HEAD and commit if needed

|

||||

if [ -f "/tmp/gh-workflows/sync-from-gitea.yml" ]; then

|

||||

mkdir -p .github/workflows

|

||||

cp /tmp/gh-workflows/sync-from-gitea.yml "$WF_PATH"

|

||||

git add "$WF_PATH"

|

||||

if ! git diff --cached --quiet; then

|

||||

git commit -m "Inject GitHub sync workflow"

|

||||

fi

|

||||

fi

|

||||

|

||||

# Force-push main so GitHub mirrors Gitea + workflow

|

||||

git push origin main --force

|

||||

1

.gitignore

vendored

1

.gitignore

vendored

@@ -143,6 +143,7 @@ analyze/

|

||||

|

||||

# pagefind postbuild

|

||||

public/_pagefind/

|

||||

public/sitemap.xml

|

||||

|

||||

# npm package lock file for different platforms

|

||||

package-lock.json

|

||||

@@ -1,7 +1,7 @@

|

||||

# Source: https://github.com/vercel/next.js/blob/canary/examples/with-docker-multi-env/docker/production/Dockerfile

|

||||

# syntax=docker.io/docker/dockerfile:1

|

||||

|

||||

FROM node:18-alpine AS base

|

||||

FROM node:20-alpine AS base

|

||||

|

||||

ENV NODE_OPTIONS="--max-old-space-size=8192"

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

@@ -28,3 +28,11 @@ Considering the memory usage for this project, it is better to deploy it as sepa

|

||||

```bash

|

||||

docker-compose up -d -f docker/docker-compose.yaml

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

### Snippets

|

||||

|

||||

Update dependencies

|

||||

|

||||

```bash

|

||||

npx npm-check-updates -u

|

||||

```

|

||||

@@ -1,12 +1,13 @@

|

||||

/* eslint-env node */

|

||||

import { Footer, Layout, Navbar } from 'nextra-theme-docs'

|

||||

import { Banner, Head } from 'nextra/components'

|

||||

import { Footer, Layout} from 'nextra-theme-docs'

|

||||

import { Head } from 'nextra/components'

|

||||

import { getPageMap } from 'nextra/page-map'

|

||||

import 'nextra-theme-docs/style.css'

|

||||

import { SpeedInsights } from "@vercel/speed-insights/next"

|

||||

import { Analytics } from "@vercel/analytics/react"

|

||||

import 'katex/dist/katex.min.css'

|

||||

import AlgoliaSearch from '../components/docsearch'

|

||||

import { Navbar } from '../components/navbar'

|

||||

|

||||

export const metadata = {

|

||||

metadataBase: new URL('https://notenextra.trance-0.com'),

|

||||

@@ -31,11 +32,13 @@ export const metadata = {

|

||||

}

|

||||

|

||||

export default async function RootLayout({ children }) {

|

||||

const pageMap = await getPageMap();

|

||||

const navbar = (

|

||||

<Navbar

|

||||

pageMap={pageMap}

|

||||

logo={

|

||||

<>

|

||||

<svg width="32" height="32" viewBox="0 0 16 16">

|

||||

<svg xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2000/svg" width="32" height="32" fill="currentColor" className="bi bi-braces-asterisk" viewBox="0 0 16 16">

|

||||

<path fillRule="evenodd" d="M1.114 8.063V7.9c1.005-.102 1.497-.615 1.497-1.6V4.503c0-1.094.39-1.538 1.354-1.538h.273V2h-.376C2.25 2 1.49 2.759 1.49 4.352v1.524c0 1.094-.376 1.456-1.49 1.456v1.299c1.114 0 1.49.362 1.49 1.456v1.524c0 1.593.759 2.352 2.372 2.352h.376v-.964h-.273c-.964 0-1.354-.444-1.354-1.538V9.663c0-.984-.492-1.497-1.497-1.6M14.886 7.9v.164c-1.005.103-1.497.616-1.497 1.6v1.798c0 1.094-.39 1.538-1.354 1.538h-.273v.964h.376c1.613 0 2.372-.759 2.372-2.352v-1.524c0-1.094.376-1.456 1.49-1.456v-1.3c-1.114 0-1.49-.362-1.49-1.456V4.352C14.51 2.759 13.75 2 12.138 2h-.376v.964h.273c.964 0 1.354.444 1.354 1.538V6.3c0 .984.492 1.497 1.497 1.6M7.5 11.5V9.207l-1.621 1.621-.707-.707L6.792 8.5H4.5v-1h2.293L5.172 5.879l.707-.707L7.5 6.792V4.5h1v2.293l1.621-1.621.707.707L9.208 7.5H11.5v1H9.207l1.621 1.621-.707.707L8.5 9.208V11.5z"/>

|

||||

</svg>

|

||||

<span style={{ marginLeft: '.4em', fontWeight: 800 }}>

|

||||

@@ -46,7 +49,6 @@ export default async function RootLayout({ children }) {

|

||||

projectLink="https://github.com/Trance-0/NoteNextra"

|

||||

/>

|

||||

)

|

||||

const pageMap = await getPageMap()

|

||||

return (

|

||||

<html lang="en" dir="ltr" suppressHydrationWarning>

|

||||

<Head color={{

|

||||

@@ -81,8 +83,8 @@ export default async function RootLayout({ children }) {

|

||||

docsRepositoryBase="https://github.com/Trance-0/NoteNextra/tree/main"

|

||||

sidebar={{ defaultMenuCollapseLevel: 1 }}

|

||||

pageMap={pageMap}

|

||||

// TODO: fix algolia search

|

||||

// search={<AlgoliaSearch />}

|

||||

// TODO: fix local search with distributed search index over containers

|

||||

search={<AlgoliaSearch/>}

|

||||

>

|

||||

{children}

|

||||

{/* SpeedInsights in vercel */}

|

||||

|

||||

@@ -2,15 +2,36 @@

|

||||

// sample code from https://docsearch.algolia.com/docs/docsearch

|

||||

|

||||

import { DocSearch } from '@docsearch/react';

|

||||

import {useTheme} from 'next-themes';

|

||||

|

||||

import '@docsearch/css';

|

||||

|

||||

function AlgoliaSearch() {

|

||||

function AlgoliaSearch () {

|

||||

const {theme, systemTheme} = useTheme();

|

||||

const darkMode = theme === 'dark' || (theme === 'system' && systemTheme === 'dark');

|

||||

// console.log("darkMode", darkMode);

|

||||

return (

|

||||

<DocSearch

|

||||

appId={process.env.NEXT_SEARCH_ALGOLIA_APP_ID || 'NKGLZZZUBC'}

|

||||

indexName={process.env.NEXT_SEARCH_ALGOLIA_INDEX_NAME || 'notenextra_trance_0'}

|

||||

apiKey={process.env.NEXT_SEARCH_ALGOLIA_API_KEY || '727b389a61e862e590dfab9ce9df31a2'}

|

||||

theme={darkMode===false ? 'light' : 'dark'}

|

||||

// this is the first time that AI is solving some problem that I have no idea how to solve

|

||||

// BEGIN OF CODE GENERATED BY AI

|

||||

transformItems={(items) =>

|

||||

// DocSearch lets you sanitize results before render. Filter out hits that don’t have a URL and give lvl0 a safe fallback.

|

||||

items

|

||||

.filter((i) => typeof i.url === 'string' && i.url) // drop records with null/empty url

|

||||

.map((i) => ({

|

||||

...i,

|

||||

hierarchy: {

|

||||

...i.hierarchy,

|

||||

// ensure strings for all places DocSearch prints text

|

||||

lvl0: i.hierarchy?.lvl0 ?? i.hierarchy?.lvl1 ?? 'Documentation',

|

||||

},

|

||||

}))

|

||||

}

|

||||

// END OF CODE GENERATED BY AI

|

||||

/>

|

||||

);

|

||||

}

|

||||

|

||||

187

components/navbar.client.tsx

Normal file

187

components/navbar.client.tsx

Normal file

@@ -0,0 +1,187 @@

|

||||

'use client'

|

||||

|

||||

import {

|

||||

MenuItem as _MenuItem,

|

||||

Menu,

|

||||

MenuButton,

|

||||

MenuItems

|

||||

} from '@headlessui/react'

|

||||

import cn from 'clsx'

|

||||

import { Anchor, Button } from 'nextra/components'

|

||||

import { useFSRoute } from 'nextra/hooks'

|

||||

import { ArrowRightIcon, MenuIcon } from 'nextra/icons'

|

||||

import type { MenuItem } from 'nextra/normalize-pages'

|

||||

import type { FC, ReactNode } from 'react'

|

||||

import { setMenu, useConfig, useMenu, useThemeConfig } from 'nextra-theme-docs'

|

||||

import { usePathname } from 'next/navigation'

|

||||

import { normalizePages } from 'nextra/normalize-pages'

|

||||

import { PageMapItem } from 'nextra'

|

||||

|

||||

const classes = {

|

||||

link: cn(

|

||||

'x:text-sm x:contrast-more:text-gray-700 x:contrast-more:dark:text-gray-100 x:whitespace-nowrap',

|

||||

'x:text-gray-600 x:hover:text-black x:dark:text-gray-400 x:dark:hover:text-gray-200',

|

||||

'x:ring-inset x:transition-colors'

|

||||

)

|

||||

}

|

||||

|

||||

const NavbarMenu: FC<{

|

||||

menu: MenuItem

|

||||

children: ReactNode

|

||||

}> = ({ menu, children }) => {

|

||||

const routes = Object.fromEntries(

|

||||

(menu.children || []).map(route => [route.name, route])

|

||||

)

|

||||

return (

|

||||

<Menu>

|

||||

<MenuButton

|

||||

className={({ focus }) =>

|

||||

cn(

|

||||

classes.link,

|

||||

'x:items-center x:flex x:gap-1.5 x:cursor-pointer',

|

||||

focus && 'x:nextra-focus'

|

||||

)

|

||||

}

|

||||

>

|

||||

{children}

|

||||

<ArrowRightIcon

|

||||

height="14"

|

||||

className="x:*:origin-center x:*:transition-transform x:*:rotate-90"

|

||||

/>

|

||||

</MenuButton>

|

||||

<MenuItems

|

||||

transition

|

||||

className={cn(

|

||||

'x:focus-visible:nextra-focus',

|

||||

'nextra-scrollbar x:motion-reduce:transition-none',

|

||||

// From https://headlessui.com/react/menu#adding-transitions

|

||||

'x:origin-top x:transition x:duration-200 x:ease-out x:data-closed:scale-95 x:data-closed:opacity-0',

|

||||

'x:border x:border-black/5 x:dark:border-white/20',

|

||||

'x:z-30 x:rounded-md x:py-1 x:text-sm x:shadow-lg',

|

||||

'x:backdrop-blur-md x:bg-nextra-bg/70',

|

||||

// headlessui adds max-height as style, use !important to override

|

||||

'x:max-h-[min(calc(100vh-5rem),256px)]!'

|

||||

)}

|

||||

anchor={{ to: 'bottom', gap: 10, padding: 16 }}

|

||||

>

|

||||

{Object.entries(

|

||||

// eslint-disable-next-line @typescript-eslint/no-unnecessary-condition -- fixme

|

||||

(menu.items as Record<string, { title: string; href?: string }>) || {}

|

||||

).map(([key, item]) => (

|

||||

<_MenuItem

|

||||

key={key}

|

||||

as={Anchor}

|

||||

href={item.href || routes[key]?.route}

|

||||

className={({ focus }) =>

|

||||

cn(

|

||||

'x:block x:py-1.5 x:transition-colors x:ps-3 x:pe-9',

|

||||

focus

|

||||

? 'x:text-gray-900 x:dark:text-gray-100'

|

||||

: 'x:text-gray-600 x:dark:text-gray-400'

|

||||

)

|

||||

}

|

||||

>

|

||||

{item.title}

|

||||

</_MenuItem>

|

||||

))}

|

||||

</MenuItems>

|

||||

</Menu>

|

||||

)

|

||||

}

|

||||

|

||||

const isMenu = (page: any): page is MenuItem => page.type === 'menu'

|

||||

|

||||

export const ClientNavbar: FC<{

|

||||

pageMap: PageMapItem[]

|

||||

children: ReactNode

|

||||

className?: string

|

||||

}> = ({ pageMap, children, className }) => {

|

||||

|

||||

const { topLevelNavbarItems } = normalizePages({

|

||||

list: pageMap,

|

||||

route: usePathname()

|

||||

})

|

||||

|

||||

// filter out titles for elements in topLevelNavbarItems with non empty route

|

||||

const existingCourseNames = new Set(

|

||||

topLevelNavbarItems.filter(

|

||||

item => !('href' in item)

|

||||

).map(item => item.title)

|

||||

)

|

||||

// console.log(existingCourseNames)

|

||||

|

||||

// filter out elements in topLevelNavbarItems with url but have title in existingCourseNames

|

||||

const filteredTopLevelNavbarItems = topLevelNavbarItems.filter(item => !('href' in item && existingCourseNames.has(item.title)))

|

||||

|

||||

// const items = topLevelNavbarItems

|

||||

// use filteredTopLevelNavbarItems to generate items

|

||||

const items = filteredTopLevelNavbarItems

|

||||

|

||||

// console.log(filteredTopLevelNavbarItems)

|

||||

const themeConfig = useThemeConfig()

|

||||

|

||||

const pathname = useFSRoute()

|

||||

const menu = useMenu()

|

||||

|

||||

return (

|

||||

<>

|

||||

<div

|

||||

className={cn(

|

||||

'x:flex x:gap-4 x:overflow-x-auto nextra-scrollbar x:py-1.5 x:max-md:hidden',

|

||||

className

|

||||

)}

|

||||

>

|

||||

{items.map((page, _index, arr) => {

|

||||

if ('display' in page && page.display === 'hidden') return

|

||||

if (isMenu(page)) {

|

||||

return (

|

||||

<NavbarMenu key={page.name} menu={page}>

|

||||

{page.title}

|

||||

</NavbarMenu>

|

||||

)

|

||||

}

|

||||

const href =

|

||||

// If it's a directory

|

||||

('frontMatter' in page ? page.route : page.firstChildRoute) ||

|

||||

page.href ||

|

||||

page.route

|

||||

|

||||

const isCurrentPage =

|

||||

href === pathname ||

|

||||

(pathname.startsWith(page.route + '/') &&

|

||||

arr.every(item => !('href' in item) || item.href !== pathname)) ||

|

||||

undefined

|

||||

|

||||

return (

|

||||

<Anchor

|

||||

href={href}

|

||||

key={page.name}

|

||||

className={cn(

|

||||

classes.link,

|

||||

'x:aria-[current]:font-medium x:aria-[current]:subpixel-antialiased x:aria-[current]:text-current'

|

||||

)}

|

||||

aria-current={isCurrentPage}

|

||||

>

|

||||

{page.title}

|

||||

</Anchor>

|

||||

)

|

||||

})}

|

||||

</div>

|

||||

{themeConfig.search && (

|

||||

<div className="x:max-md:hidden">{themeConfig.search}</div>

|

||||

)}

|

||||

|

||||

{children}

|

||||

|

||||

<Button

|

||||

aria-label="Menu"

|

||||

className={({ active }) =>

|

||||

cn('nextra-hamburger x:md:hidden', active && 'x:bg-gray-400/20')

|

||||

}

|

||||

onClick={() => setMenu(prev => !prev)}

|

||||

>

|

||||

<MenuIcon height="24" className={cn({ open: menu })} />

|

||||

</Button>

|

||||

</>

|

||||

)

|

||||

}

|

||||

168

components/navbar.tsx

Normal file

168

components/navbar.tsx

Normal file

@@ -0,0 +1,168 @@

|

||||

// customized navbar component, modified from https://github.com/shuding/nextra/blob/c8238813e1ba425cdd72783d57707b0ff3ca52ea/examples/custom-theme/app/_components/navbar.tsx#L9

|

||||

|

||||

// Rebuild from source code https://github.com/shuding/nextra/tree/c8238813e1ba425cdd72783d57707b0ff3ca52ea/packages/nextra-theme-docs/src/components/navbar

|

||||

|

||||

'use client'

|

||||

|

||||

import type { PageMapItem } from 'nextra'

|

||||

import { Anchor } from 'nextra/components'

|

||||

import type { FC, ReactNode } from 'react'

|

||||

|

||||

import cn from 'clsx'

|

||||

// eslint-disable-next-line no-restricted-imports -- since we don't need `newWindow` prop

|

||||

import NextLink from 'next/link'

|

||||

import { DiscordIcon, GitHubIcon } from 'nextra/icons'

|

||||

import { ClientNavbar } from './navbar.client'

|

||||

|

||||

// export const Navbar: FC<{ pageMap: PageMapItem[] }> = ({ pageMap }) => {

|

||||

// const pathname = usePathname()

|

||||

// const { topLevelNavbarItems } = normalizePages({

|

||||

// list: pageMap,

|

||||

// route: pathname

|

||||

// })

|

||||

// return (

|

||||

// <ul

|

||||

// style={{

|

||||

// display: 'flex',

|

||||

// listStyleType: 'none',

|

||||

// padding: 20,

|

||||

// gap: 20,

|

||||

// background: 'lightcoral',

|

||||

// margin: 0

|

||||

// }}

|

||||

// >

|

||||

// {filteredTopLevelNavbarItems.map(item => {

|

||||

|

||||

// const route = item.route || ('href' in item ? item.href! : '')

|

||||

// return (

|

||||

// <li key={route}>

|

||||

// <Anchor href={route} style={{ textDecoration: 'none' }}>

|

||||

// {item.title}

|

||||

// </Anchor>

|

||||

// </li>

|

||||

// )

|

||||

// })}

|

||||

// </ul>

|

||||

// )

|

||||

// }

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

/* TODO: eslint typescript-sort-keys/interface: error */

|

||||

|

||||

interface NavbarProps {

|

||||

/**

|

||||

* Page map.

|

||||

*/

|

||||

pageMap: PageMapItem[]

|

||||

/**

|

||||

* Extra content after the last icon.

|

||||

*/

|

||||

children?: ReactNode

|

||||

/**

|

||||

* Specifies whether the logo should have a link or provides the URL for the logo's link.

|

||||

* @default true

|

||||

*/

|

||||

logoLink?: string | boolean

|

||||

/**

|

||||

* Logo of the website.

|

||||

*/

|

||||

logo: ReactNode

|

||||

/**

|

||||

* URL of the project homepage.

|

||||

*/

|

||||

projectLink?: string

|

||||

/**

|

||||

* Icon of the project link.

|

||||

* @default <GitHubIcon />

|

||||

*/

|

||||

projectIcon?: ReactNode

|

||||

/**

|

||||

* URL of the chat link.

|

||||

*/

|

||||

chatLink?: string

|

||||

/**

|

||||

* Icon of the chat link.

|

||||

* @default <DiscordIcon />

|

||||

*/

|

||||

chatIcon?: ReactNode

|

||||

/**

|

||||

* CSS class name.

|

||||

*/

|

||||

className?: string

|

||||

/**

|

||||

* Aligns navigation links to the specified side.

|

||||

* @default 'right'

|

||||

*/

|

||||

align?: 'left' | 'right'

|

||||

}

|

||||

|

||||

// Fix compiler error

|

||||

// Expression type `JSXElement` cannot be safely reordered

|

||||

const defaultGitHubIcon = (

|

||||

<GitHubIcon height="24" aria-label="Project repository" />

|

||||

)

|

||||

const defaultChatIcon = <DiscordIcon width="24" />

|

||||

|

||||

export const Navbar: FC<NavbarProps> = ({

|

||||

pageMap,

|

||||

children,

|

||||

logoLink = true,

|

||||

logo,

|

||||

projectLink,

|

||||

projectIcon = defaultGitHubIcon,

|

||||

chatLink,

|

||||

chatIcon = defaultChatIcon,

|

||||

className,

|

||||

align = 'right'

|

||||

}) => {

|

||||

const logoClass = cn(

|

||||

'x:flex x:items-center',

|

||||

align === 'left' ? 'x:max-md:me-auto' : 'x:me-auto'

|

||||

)

|

||||

return (

|

||||

<header

|

||||

className={cn(

|

||||

'nextra-navbar x:sticky x:top-0 x:z-30 x:w-full x:bg-transparent x:print:hidden',

|

||||

'x:max-md:[.nextra-banner:not([class$=hidden])~&]:top-(--nextra-banner-height)'

|

||||

)}

|

||||

>

|

||||

<div

|

||||

className={cn(

|

||||

'nextra-navbar-blur',

|

||||

'x:absolute x:-z-1 x:size-full',

|

||||

'nextra-border x:border-b',

|

||||

'x:backdrop-blur-md x:bg-nextra-bg/70'

|

||||

)}

|

||||

/>

|

||||

<nav

|

||||

style={{ height: 'var(--nextra-navbar-height)' }}

|

||||

className={cn(

|

||||

'x:mx-auto x:flex x:max-w-(--nextra-content-width) x:items-center x:gap-4 x:pl-[max(env(safe-area-inset-left),1.5rem)] x:pr-[max(env(safe-area-inset-right),1.5rem)]',

|

||||

'x:justify-end',

|

||||

className

|

||||

)}

|

||||

>

|

||||

{logoLink ? (

|

||||

<NextLink

|

||||

href={typeof logoLink === 'string' ? logoLink : '/'}

|

||||

className={cn(

|

||||

logoClass,

|

||||

'x:transition-opacity x:focus-visible:nextra-focus x:hover:opacity-75'

|

||||

)}

|

||||

aria-label="Home page"

|

||||

>

|

||||

{logo}

|

||||

</NextLink>

|

||||

) : (

|

||||

<div className={logoClass}>{logo}</div>

|

||||

)}

|

||||

<ClientNavbar pageMap={pageMap}

|

||||

className={align === 'left' ? 'x:me-auto' : ''}>

|

||||

{projectLink && <Anchor href={projectLink}>{projectIcon}</Anchor>}

|

||||

{chatLink && <Anchor href={chatLink}>{chatIcon}</Anchor>}

|

||||

{children}

|

||||

</ClientNavbar>

|

||||

</nav>

|

||||

</header>

|

||||

)

|

||||

}

|

||||

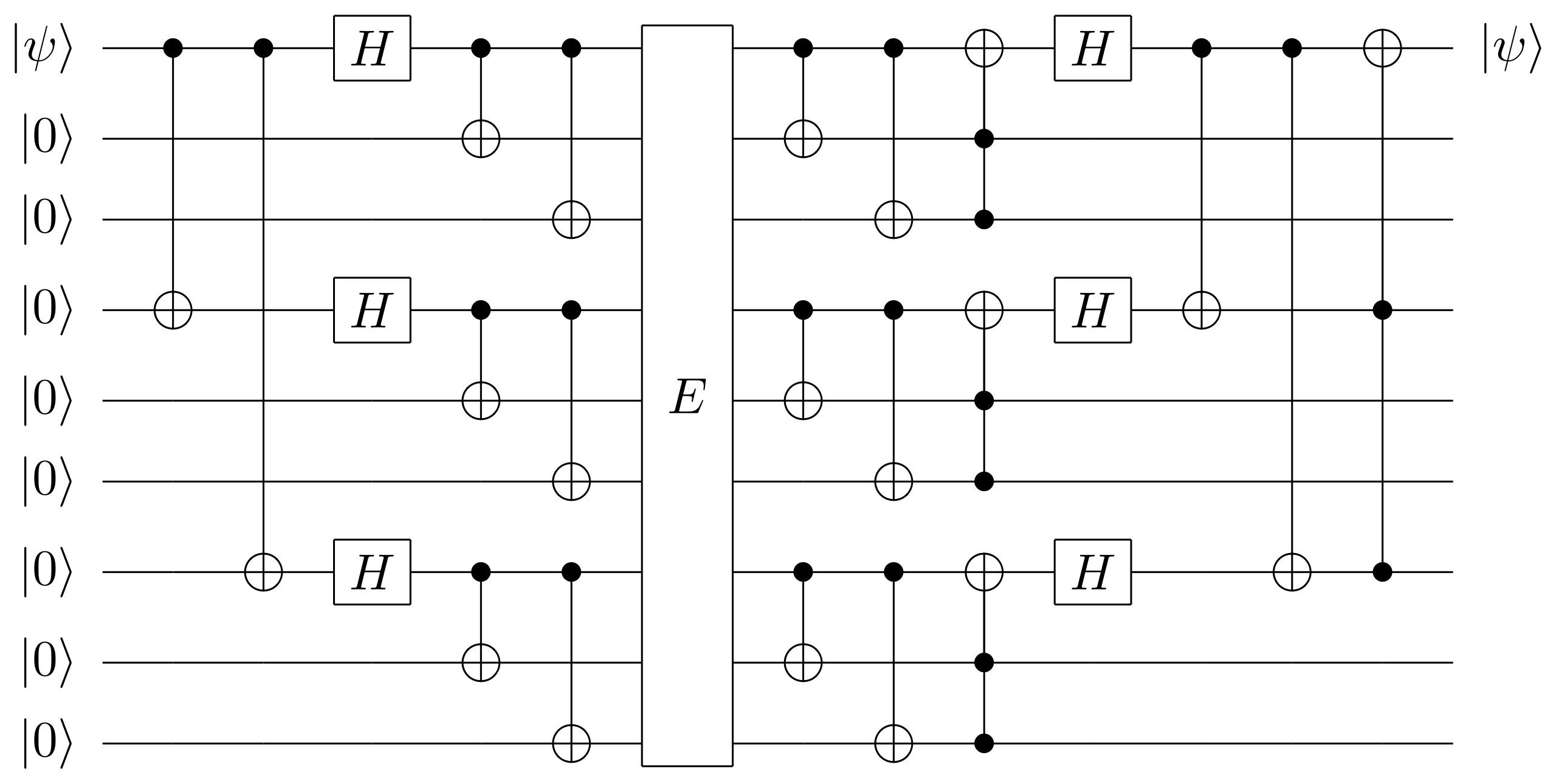

@@ -13,7 +13,8 @@ Ouput $(r,m\oplus f_i(r))$

|

||||

|

||||

$Dec_i(r,c):$ Output $c\oplus f_i(r)$

|

||||

|

||||

Proof of security:

|

||||

<details>

|

||||

<summary>Proof of security</summary>

|

||||

|

||||

Suppose $D$ distinguishes, for infinitly many $n$.

|

||||

|

||||

@@ -35,7 +36,7 @@ $(r_1,F(r_1)),\ldots, (r_q,F(r_q))$

|

||||

|

||||

So $D$ distinguishing output of $r_1,\ldots, r_q$ of PRF from the RF, this contradicts with definition of PRF.

|

||||

|

||||

QED

|

||||

</details>

|

||||

|

||||

Noe we have

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

@@ -32,7 +32,8 @@ Proof of the validity of the decryption: Exercise.

|

||||

|

||||

The encryption scheme is secure under this construction (Trapdoor permutation (TDP), Hardcore bit (HCB)).

|

||||

|

||||

Proof:

|

||||

<details>

|

||||

<summary>Proof</summary>

|

||||

|

||||

We proceed by contradiction. (Constructing contradiction with definition of hardcore bit.)

|

||||

|

||||

@@ -76,7 +77,7 @@ $$

|

||||

|

||||

This contradicts the definition of hardcore bit.

|

||||

|

||||

QED

|

||||

</details>

|

||||

|

||||

### Public key encryption scheme (multi-bit)

|

||||

|

||||

@@ -144,7 +145,8 @@ Output: $m$

|

||||

|

||||

#### Security of El-Gamal encryption scheme

|

||||

|

||||

Proof:

|

||||

<details>

|

||||

<summary>Proof</summary>

|

||||

|

||||

If not secure, then there exists a distinguisher $\mathcal{D}$ that can distinguish the encryption of $m_1,m_2\in G_q$ with non-negligible probability $\mu(n)$.

|

||||

|

||||

@@ -155,5 +157,5 @@ $$

|

||||

|

||||

And proceed by contradiction. This contradicts the DDH assumption.

|

||||

|

||||

QED

|

||||

</details>

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

@@ -26,7 +26,8 @@ Under the discrete log assumption, $H$ is a CRHF.

|

||||

- It is easy to compute

|

||||

- Compressing by 1 bit

|

||||

|

||||

Proof:

|

||||

<details>

|

||||

<summary>Proof</summary>

|

||||

|

||||

The hash function $h$ is a CRHF

|

||||

|

||||

@@ -72,7 +73,7 @@ So $\mathcal{B}$ can break the discrete log assumption with non-negligible proba

|

||||

|

||||

So $h$ is a CRHF.

|

||||

|

||||

QED

|

||||

</details>

|

||||

|

||||

To compress by more, say $h_k:{0,1}^n\to \{0,1\}^{n-k},k\geq 1$, then we can use $h: \{0,1\}^{n+1}\to \{0,1\}^n$ multiple times.

|

||||

|

||||

@@ -106,7 +107,8 @@ One-time secure:

|

||||

|

||||

Then ($Gen',Sign',Ver'$) is one-time secure.

|

||||

|

||||

Ideas of Proof:

|

||||

<details>

|

||||

<summary>Ideas of Proof</summary>

|

||||

|

||||

If the digital signature scheme ($Gen',Sign',Ver'$) is not one-time secure, then there exists an adversary $\mathcal{A}$ which can ask oracle for one signature on $m_1$ and receive $\sigma_1=Sign'_{sk'}(m_1)=Sign_{sk}(h_i(m_1))$.

|

||||

|

||||

@@ -119,7 +121,7 @@ Case 1: $h_i(m_1)=h_i(m_2)$, Then $\mathcal{A}$ finds a collision of $h$.

|

||||

|

||||

Case 2: $h_i(m_1)\neq h_i(m_2)$, Then $\mathcal{A}$ produced valid signature on $h_i(m_2)$ after only seeing $Sign'_{sk'}(m_1)\neq Sign'_{sk'}(m_2)$. This contradicts the one-time secure of ($Gen,Sign,Ver$).

|

||||

|

||||

QED

|

||||

</details>

|

||||

|

||||

### Many-time Secure Digital Signature

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

@@ -8,7 +8,7 @@ One-way functions, Pseudorandomness, Private-key cryptography, Public-key crypto

|

||||

|

||||

### Instructor

|

||||

|

||||

[Brian Garnett](bcgarnett@wustl.edu)

|

||||

Brian Garnett (bcgarnett@wustl.edu)

|

||||

|

||||

Math Phd… Great!

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

@@ -198,20 +198,20 @@ $$

|

||||

|

||||

Take the softmax policy as example:

|

||||

|

||||

Weight actions using the linear combination of features $\phi(s,a)^T\theta$:

|

||||

Weight actions using the linear combination of features $\phi(s,a)^\top\theta$:

|

||||

|

||||

Probability of action is proportional to the exponentiated weights:

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\pi_\theta(s,a) \propto \exp(\phi(s,a)^T\theta)

|

||||

\pi_\theta(s,a) \propto \exp(\phi(s,a)^\top\theta)

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

The score function is

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\begin{aligned}

|

||||

\nabla_\theta \ln\left[\frac{\exp(\phi(s,a)^T\theta)}{\sum_{a'\in A}\exp(\phi(s,a')^T\theta)}\right] &= \nabla_\theta(\ln \exp(\phi(s,a)^T\theta) - (\ln \sum_{a'\in A}\exp(\phi(s,a')^T\theta))) \\

|

||||

&= \nabla_\theta\left(\phi(s,a)^T\theta -\frac{\phi(s,a)\sum_{a'\in A}\exp(\phi(s,a')^T\theta)}{\sum_{a'\in A}\exp(\phi(s,a')^T\theta)}\right) \\

|

||||

\nabla_\theta \ln\left[\frac{\exp(\phi(s,a)^\top\theta)}{\sum_{a'\in A}\exp(\phi(s,a')^\top\theta)}\right] &= \nabla_\theta(\ln \exp(\phi(s,a)^\top\theta) - (\ln \sum_{a'\in A}\exp(\phi(s,a')^\top\theta))) \\

|

||||

&= \nabla_\theta\left(\phi(s,a)^\top\theta -\frac{\phi(s,a)\sum_{a'\in A}\exp(\phi(s,a')^\top\theta)}{\sum_{a'\in A}\exp(\phi(s,a')^\top\theta)}\right) \\

|

||||

&=\phi(s,a) - \sum_{a'\in A} \prod_\theta(s,a') \phi(s,a')

|

||||

&= \phi(s,a) - \mathbb{E}_{a'\sim \pi_\theta(s,a')}[\phi(s,a')]

|

||||

\end{aligned}

|

||||

@@ -221,7 +221,7 @@ $$

|

||||

|

||||

In continuous action spaces, a Gaussian policy is natural

|

||||

|

||||

Mean is a linear combination of state features $\mu(s) = \phi(s)^T\theta$

|

||||

Mean is a linear combination of state features $\mu(s) = \phi(s)^\top\theta$

|

||||

|

||||

Variance may be fixed $\sigma^2$, or can also parametrized

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

@@ -53,7 +53,7 @@ $$

|

||||

Action-Value Actor-Critic

|

||||

|

||||

- Simple actor-critic algorithm based on action-value critic

|

||||

- Using linear value function approximation $Q_w(s,a)=\phi(s,a)^T w$

|

||||

- Using linear value function approximation $Q_w(s,a)=\phi(s,a)^\top w$

|

||||

|

||||

Critic: updates $w$ by linear $TD(0)$

|

||||

Actor: updates $\theta$ by policy gradient

|

||||

|

||||

@@ -193,7 +193,7 @@ $$

|

||||

|

||||

Make linear approximation to $L_{\pi_{\theta_{old}}}$ and quadratic approximation to KL term.

|

||||

|

||||

Maximize $g\cdot(\theta-\theta_{old})-\frac{\beta}{2}(\theta-\theta_{old})^T F(\theta-\theta_{old})$

|

||||

Maximize $g\cdot(\theta-\theta_{old})-\frac{\beta}{2}(\theta-\theta_{old})^\top F(\theta-\theta_{old})$

|

||||

|

||||

where $g=\frac{\partial}{\partial \theta}L_{\pi_{\theta_{old}}}(\pi_{\theta})\vert_{\theta=\theta_{old}}$ and $F=\frac{\partial^2}{\partial \theta^2}\overline{KL}_{\pi_{\theta_{old}}}(\pi_{\theta})\vert_{\theta=\theta_{old}}$

|

||||

|

||||

@@ -201,7 +201,7 @@ where $g=\frac{\partial}{\partial \theta}L_{\pi_{\theta_{old}}}(\pi_{\theta})\ve

|

||||

<summary>Taylor Expansion of KL Term</summary>

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

D_{KL}(\pi_{\theta_{old}}|\pi_{\theta})\approx D_{KL}(\pi_{\theta_{old}}|\pi_{\theta_{old}})+d^T \nabla_\theta D_{KL}(\pi_{\theta_{old}}|\pi_{\theta})\vert_{\theta=\theta_{old}}+\frac{1}{2}d^T \nabla_\theta^2 D_{KL}(\pi_{\theta_{old}}|\pi_{\theta})\vert_{\theta=\theta_{old}}d

|

||||

D_{KL}(\pi_{\theta_{old}}|\pi_{\theta})\approx D_{KL}(\pi_{\theta_{old}}|\pi_{\theta_{old}})+d^\top \nabla_\theta D_{KL}(\pi_{\theta_{old}}|\pi_{\theta})\vert_{\theta=\theta_{old}}+\frac{1}{2}d^\top \nabla_\theta^2 D_{KL}(\pi_{\theta_{old}}|\pi_{\theta})\vert_{\theta=\theta_{old}}d

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

@@ -220,9 +220,9 @@ $$

|

||||

\begin{aligned}

|

||||

\nabla_\theta^2 D_{KL}(\pi_{\theta_{old}}|\pi_{\theta})\vert_{\theta=\theta_{old}}&=-\mathbb{E}_{x\sim \pi_{\theta_{old}}}\nabla_\theta^2 \log P_\theta(x)\vert_{\theta=\theta_{old}}\\

|

||||

&=-\mathbb{E}_{x\sim \pi_{\theta_{old}}}\nabla_\theta \left(\frac{\nabla_\theta P_\theta(x)}{P_\theta(x)}\right)\vert_{\theta=\theta_{old}}\\

|

||||

&=-\mathbb{E}_{x\sim \pi_{\theta_{old}}}\left(\frac{\nabla_\theta^2 P_\theta(x)-\nabla_\theta P_\theta(x)\nabla_\theta P_\theta(x)^T}{P_\theta(x)^2}\right)\vert_{\theta=\theta_{old}}\\

|

||||

&=-\mathbb{E}_{x\sim \pi_{\theta_{old}}}\left(\frac{\nabla_\theta^2 P_\theta(x)\vert_{\theta=\theta_{old}}}P_{\theta_{old}}(x)\right)+\mathbb{E}_{x\sim \pi_{\theta_{old}}}\left(\nabla_\theta \log P_\theta(x)\nabla_\theta \log P_\theta(x)^T\right)\vert_{\theta=\theta_{old}}\\

|

||||

&=\mathbb{E}_{x\sim \pi_{\theta_{old}}}\nabla_\theta\log P_\theta(x)\nabla_\theta\log P_\theta(x)^T\vert_{\theta=\theta_{old}}\\

|

||||

&=-\mathbb{E}_{x\sim \pi_{\theta_{old}}}\left(\frac{\nabla_\theta^2 P_\theta(x)-\nabla_\theta P_\theta(x)\nabla_\theta P_\theta(x)^\top}{P_\theta(x)^2}\right)\vert_{\theta=\theta_{old}}\\

|

||||

&=-\mathbb{E}_{x\sim \pi_{\theta_{old}}}\left(\frac{\nabla_\theta^2 P_\theta(x)\vert_{\theta=\theta_{old}}}P_{\theta_{old}}(x)\right)+\mathbb{E}_{x\sim \pi_{\theta_{old}}}\left(\nabla_\theta \log P_\theta(x)\nabla_\theta \log P_\theta(x)^\top\right)\vert_{\theta=\theta_{old}}\\

|

||||

&=\mathbb{E}_{x\sim \pi_{\theta_{old}}}\nabla_\theta\log P_\theta(x)\nabla_\theta\log P_\theta(x)^\top\vert_{\theta=\theta_{old}}\\

|

||||

\end{aligned}

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

@@ -27,7 +27,7 @@ $\theta_{new}=\theta_{old}+d$

|

||||

First order Taylor expansion for the loss and second order for the KL:

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\approx \arg\max_{d} J(\theta_{old})+\nabla_\theta J(\theta)\mid_{\theta=\theta_{old}}d-\frac{1}{2}\lambda(d^T\nabla_\theta^2 D_{KL}\left[\pi_{\theta_{old}}||\pi_{\theta}\right]\mid_{\theta=\theta_{old}}d)+\lambda \delta

|

||||

\approx \arg\max_{d} J(\theta_{old})+\nabla_\theta J(\theta)\mid_{\theta=\theta_{old}}d-\frac{1}{2}\lambda(d^\top\nabla_\theta^2 D_{KL}\left[\pi_{\theta_{old}}||\pi_{\theta}\right]\mid_{\theta=\theta_{old}}d)+\lambda \delta

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

If you are really interested, try to fill the solving the KL Constrained Problem section.

|

||||

@@ -38,7 +38,7 @@ Setting the gradient to zero:

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\begin{aligned}

|

||||

0&=\frac{\partial}{\partial d}\left(-\nabla_\theta J(\theta)\mid_{\theta=\theta_{old}}d+\frac{1}{2}\lambda(d^T F(\theta_{old})d\right)\\

|

||||

0&=\frac{\partial}{\partial d}\left(-\nabla_\theta J(\theta)\mid_{\theta=\theta_{old}}d+\frac{1}{2}\lambda(d^\top F(\theta_{old})d\right)\\

|

||||

&=-\nabla_\theta J(\theta)\mid_{\theta=\theta_{old}}+\frac{1}{2}\lambda F(\theta_{old})d

|

||||

\end{aligned}

|

||||

$$

|

||||

@@ -58,15 +58,15 @@ $$

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

D_{KL}(\pi_{\theta_{old}}||\pi_{\theta})\approx \frac{1}{2}(\theta-\theta_{old})^T F(\theta_{old})(\theta-\theta_{old})

|

||||

D_{KL}(\pi_{\theta_{old}}||\pi_{\theta})\approx \frac{1}{2}(\theta-\theta_{old})^\top F(\theta_{old})(\theta-\theta_{old})

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\frac{1}{2}(\alpha g_N)^T F(\alpha g_N)=\delta

|

||||

\frac{1}{2}(\alpha g_N)^\top F(\alpha g_N)=\delta

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\alpha=\sqrt{\frac{2\delta}{g_N^T F g_N}}

|

||||

\alpha=\sqrt{\frac{2\delta}{g_N^\top F g_N}}

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

However, due to the quadratic approximation, the KL constrains may be violated.

|

||||

|

||||

@@ -1,14 +1,47 @@

|

||||

# CSE510 Deep Reinforcement Learning (Lecture 17)

|

||||

|

||||

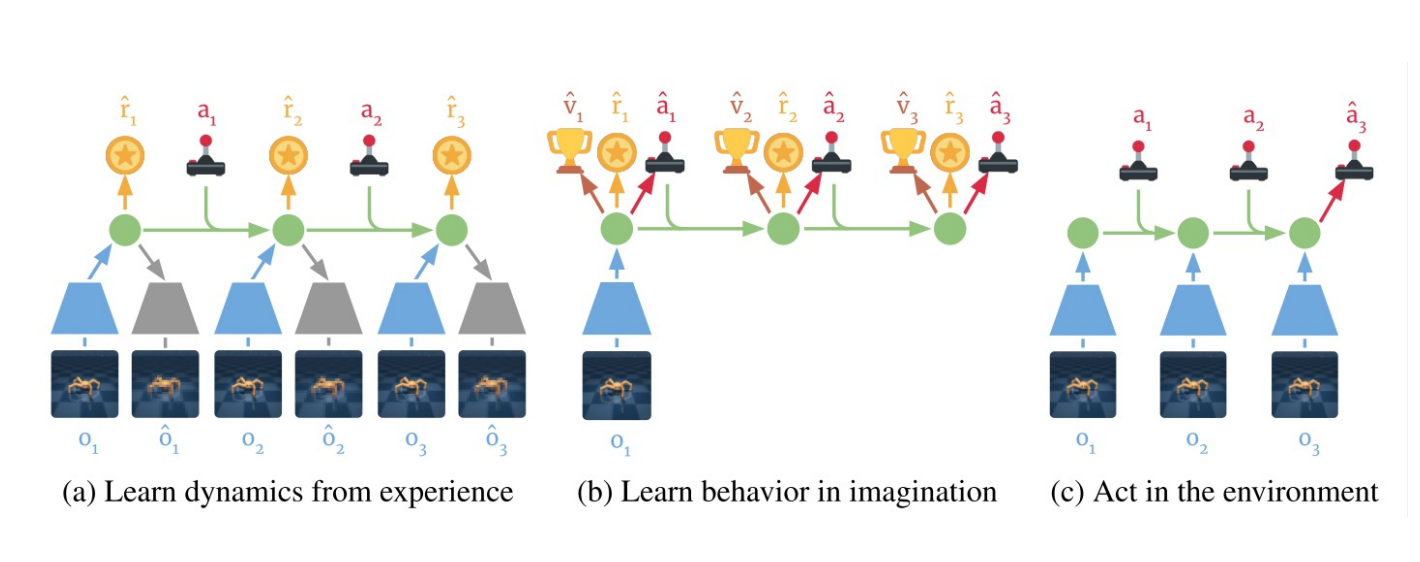

## Model-based RL

|

||||

|

||||

### Model-based RL vs. Model-free RL

|

||||

## Why Model-Based RL?

|

||||

|

||||

- Sample efficiency

|

||||

- Generalization and transferability

|

||||

- Support efficient exploration in large-scale RL problems

|

||||

- Explainability

|

||||

- Super-human performance in practice

|

||||

- Video games, Go, Algorithm discovery, etc.

|

||||

|

||||

> [!NOTE]

|

||||

>

|

||||

> Model is anything the agent can use to predict how the environment will respond to its actions, concretely, the state transition $T(s'| s, a)$ and reward $R(s, a)$.

|

||||

|

||||

For ADP-based (model-based) RL

|

||||

|

||||

1. Start with initial model

|

||||

2. Solve for optimal policy given current model

|

||||

- (using value or policy iteration)

|

||||

3. Take action according to an exploration/exploitation policy

|

||||

- Explores more early on and gradually uses policy from 2

|

||||

4. Update estimated model based on observed transition

|

||||

5. Goto 2

|

||||

|

||||

### Problems in Large Scale Model-Based RL

|

||||

|

||||

- New planning methods for given a model

|

||||

- Model is large and not perfect

|

||||

- Model learning

|

||||

- Requiring generalization

|

||||

- Exploration/exploitation strategy

|

||||

- Requiring generalization and attention

|

||||

|

||||

### Large Scale Model-Based RL

|

||||

|

||||

- New optimal planning methods (Today)

|

||||

- Model is large and not perfect

|

||||

- Model learning (Next Lecture)

|

||||

- Requiring generalization

|

||||

- Exploration/exploitation strategy (Next week)

|

||||

- Requiring generalization and attention

|

||||

|

||||

## Model-based RL

|

||||

|

||||

### Deterministic Environment: Cross-Entropy Method

|

||||

|

||||

@@ -29,12 +62,14 @@ Simplest method: guess and check: "random shooting method"

|

||||

- pick $A_1, A_2, ..., A_n$ from some distribution (e.g. uniform)

|

||||

- Choose $A_i$ based on $\argmax_i J(A_i)$

|

||||

|

||||

#### Cross-Entropy Method with continuous-valued inputs

|

||||

#### Cross-Entropy Method (CEM) with continuous-valued inputs

|

||||

|

||||

1. sample $A_1, A_2, ..., A_n$ from some distribution $p(A)$

|

||||

2. evaluate $J(A_1), J(A_2), ..., J(A_n)$

|

||||

3. pick the _elites_ $A_1, A_2, ..., A_m$ with the highest $J(A_i)$, where $m<n$

|

||||

4. update the distribution $p(A)$ to be more likely to choose the elites

|

||||

Cross-entropy method with continuous-valued inputs:s

|

||||

|

||||

1. Sample $A_1, A_2, ..., A_n$ from some distribution $p(A)$

|

||||

2. Evaluate $J(A_1), J(A_2), ..., J(A_n)$

|

||||

3. Pick the _elites_ $A_1, A_2, ..., A_m$ with the highest $J(A_i)$, where $m<n$

|

||||

4. Update the distribution $p(A)$ to be more likely to choose the elites

|

||||

|

||||

Pros:

|

||||

|

||||

@@ -68,15 +103,70 @@ Use model as simulator to evaluate actions.

|

||||

|

||||

Tree policy:

|

||||

|

||||

Decision policy:

|

||||

- Select/create leaf node

|

||||

- Selection and Expansion

|

||||

- Bandit problem!

|

||||

|

||||

Default policy/rollout policy

|

||||

|

||||

- Play the game till end

|

||||

- Simulation

|

||||

|

||||

Decision policy

|

||||

|

||||

- Selecting the final action

|

||||

|

||||

#### Upper Confidence Bound on Trees (UCT)

|

||||

|

||||

Selecting Child Node - Multi-Arm Bandit Problem

|

||||

|

||||

UCB1 applied for each child selection

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

UCT=\overline{X_j}+2C_p\sqrt{\frac{2\ln n_j}{n_j}}

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

- where $\overline{X_j}$ is the mean reward of selecting this position

|

||||

- $[0,1]$

|

||||

- $n$ is the number of times current(parent) node has been visited

|

||||

- $n_j$ is the number of times child node $j$ has been visited

|

||||

- Guaranteed we explore each child node at least once

|

||||

- $C_p$ is some constant $>0$

|

||||

|

||||

Each child has non-zero probability of being selected

|

||||

|

||||

We can adjust $C_p$ to change exploration vs. exploitation trade-off

|

||||

|

||||

#### Decision Policy: Final Action Selection

|

||||

|

||||

Selecting the best child

|

||||

|

||||

- Max (highest weight)

|

||||

- Robust (most visits)

|

||||

- Max-Robust (max of the two)

|

||||

|

||||

#### Upper Confidence Bound on Trees (UCT)

|

||||

#### Advantages and disadvantages of MCTS

|

||||

|

||||

Advantages:

|

||||

|

||||

- Proved MCTS converges to minimax solution

|

||||

- Domain-independent

|

||||

- Anytime algorithm

|

||||

- Achieving better with a large branch factor

|

||||

|

||||

Disadvantages:

|

||||

|

||||

- Basic version converges very slowly

|

||||

- Leading to small-probability failures

|

||||

|

||||

### Example usage of MCTS

|

||||

|

||||

AlphaGo vs Lee Sedol, Game 4

|

||||

|

||||

- White 78 (Lee): unexpected move (even other professional players didn't see coming) - needle in the haystack

|

||||

- AlphaGo failed to explore this in MCTS

|

||||

|

||||

Imitation learning from MCTS:

|

||||

|

||||

#### Continuous Case: Trajectory Optimization

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

65

content/CSE510/CSE510_L18.md

Normal file

65

content/CSE510/CSE510_L18.md

Normal file

@@ -0,0 +1,65 @@

|

||||

# CSE510 Deep Reinforcement Learning (Lecture 18)

|

||||

|

||||

## Model-based RL framework

|

||||

|

||||

Model Learning with High-Dimensional Observations

|

||||

|

||||

- Learning model in a latent space with observation reconstruction

|

||||

- Learning model in a latent space without observation reconstruction

|

||||

- Learning model in the observation space (i.e., videos)

|

||||

|

||||

### Naive approach:

|

||||

|

||||

If we knew $f(s_t,a_t)=s_{t+1}$, we could use the tools from last week. (or $p(s_{t+1}| s_t, a_t)$ in the stochastic case)

|

||||

|

||||

So we can learn $f(s_t,a_t)$ from data, and _then_ plan through it.

|

||||

|

||||

Model-based reinforcement learning version **0.5**:

|

||||

|

||||

1. Run base polity $\pi_0$ (e.g. random policy) to collect $\mathcal{D} = \{(s_t, a_t, s_{t+1})\}_{t=0}^\top$

|

||||

2. Learn dynamics model $f(s_t,a_t)$ to minimize $\sum_{i}\|f(s_i,a_i)-s_{i+1}\|^2$

|

||||

3. Plan through $f(s_t,a_t)$ to choose action $a_t$

|

||||

|

||||

Sometime, it does work!

|

||||

|

||||

- Essentially how system identification works in classical robotics

|

||||

- Some care should be taken to design a good base policy

|

||||

- Particularly effective if we can hand-engineer a dynamics representation using our knowledge of physics, and fit just a few parameters

|

||||

|

||||

However, Distribution mismatch problem becomes worse as we use more

|

||||

expressive model classes.

|

||||

|

||||

Version 0.5: collect random samples, train dynamics, plan

|

||||

|

||||

- Pro: simple, no iterative procedure

|

||||

- Con: distribution mismatch problem

|

||||

|

||||

Version 1.0: iteratively collect data, replan, collect data

|

||||

|

||||

- Pro: simple, solves distribution mismatch

|

||||

- Con: open loop plan might perform poorly, esp. in stochastic domains

|

||||

|

||||

Version 1.5: iteratively collect data using MPC (replan at each step)

|

||||

|

||||

- Pro: robust to small model errors

|

||||

- Con: computationally expensive, but have a planning algorithm available

|

||||

|

||||

Version 2.0: backpropagate directly into policy

|

||||

|

||||

- Pro: computationally cheap at runtime

|

||||

- Con: can be numerically unstable, especially in stochastic domains

|

||||

- Solution: model-free RL + model-based RL

|

||||

|

||||

Final version:

|

||||

|

||||

1. Run base polity $\pi_0$ (e.g. random policy) to collect $\mathcal{D} = \{(s_t, a_t, s_{t+1})\}_{t=0}^\top$

|

||||

2. Learn dynamics model $f(s_t,a_t)$ to minimize $\sum_{i}\|f(s_i,a_i)-s_{i+1}\|^2$

|

||||

3. Backpropagate through $f(s_t,a_t)$ into the policy to optimized $\pi_\theta(s_t,a_t)$

|

||||

4. Run the policy $\pi_\theta(s_t,a_t)$ to collect $\mathcal{D} = \{(s_t, a_t, s_{t+1})\}_{t=0}^\top$

|

||||

5. Goto 2

|

||||

|

||||

## Model Learning with High-Dimensional Observations

|

||||

|

||||

- Learning model in a latent space with observation reconstruction

|

||||

- Learning model in a latent space without observation reconstruction

|

||||

|

||||

100

content/CSE510/CSE510_L19.md

Normal file

100

content/CSE510/CSE510_L19.md

Normal file

@@ -0,0 +1,100 @@

|

||||

# CSE510 Deep Reinforcement Learning (Lecture 19)

|

||||

|

||||

## Model learning with high-dimensional observations

|

||||

|

||||

- Learning model in a latent space with observation reconstruction

|

||||

- Learning model in a latent space without reconstruction

|

||||

|

||||

### Learn in Latent Space: Dreamer

|

||||

|

||||

Learning embedding of images & dynamics model (jointly)

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

Representation model: $p_\theta(s_t|s_{t-1}, a_{t-1}, o_t)$

|

||||

|

||||

Observation model: $q_\theta(o_t|s_t)$

|

||||

|

||||

Reward model: $q_\theta(r_t|s_t)$

|

||||

|

||||

Transition model: $q_\theta(s_t| s_{t-1}, a_{t-1})$.

|

||||

|

||||

Variational evidence lower bound (ELBO) objective:

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\mathcal{J}_{REC}\doteq \mathbb{E}_{p}\left(\sum_t(\mathcal{J}_O^t+\mathcal{J}_R^t+\mathcal{J}_D^t)\right)

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

where

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\mathcal{J}_O^t\doteq \ln q(o_t|s_t)

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\mathcal{J}_R^t\doteq \ln q(r_t|s_t)

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\mathcal{J}_D^t\doteq -\beta \operatorname{KL}(p(s_t|s_{t-1}, a_{t-1}, o_t)||q(s_t|s_{t-1}, a_{t-1}))

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

#### More versions for Dreamer

|

||||

|

||||

Latest is V3, [link to the paper](https://arxiv.org/pdf/2301.04104)

|

||||

|

||||

### Learn in Latent Space

|

||||

|

||||

- Pros

|

||||

- Learn visual skill efficiently (using relative simple networks)

|

||||

- Cons

|

||||

- Using autoencoder might not recover the right representation

|

||||

- Not necessarily suitable for model-based methods

|

||||

- Embedding is often not a good state representation without using history observations

|

||||

|

||||

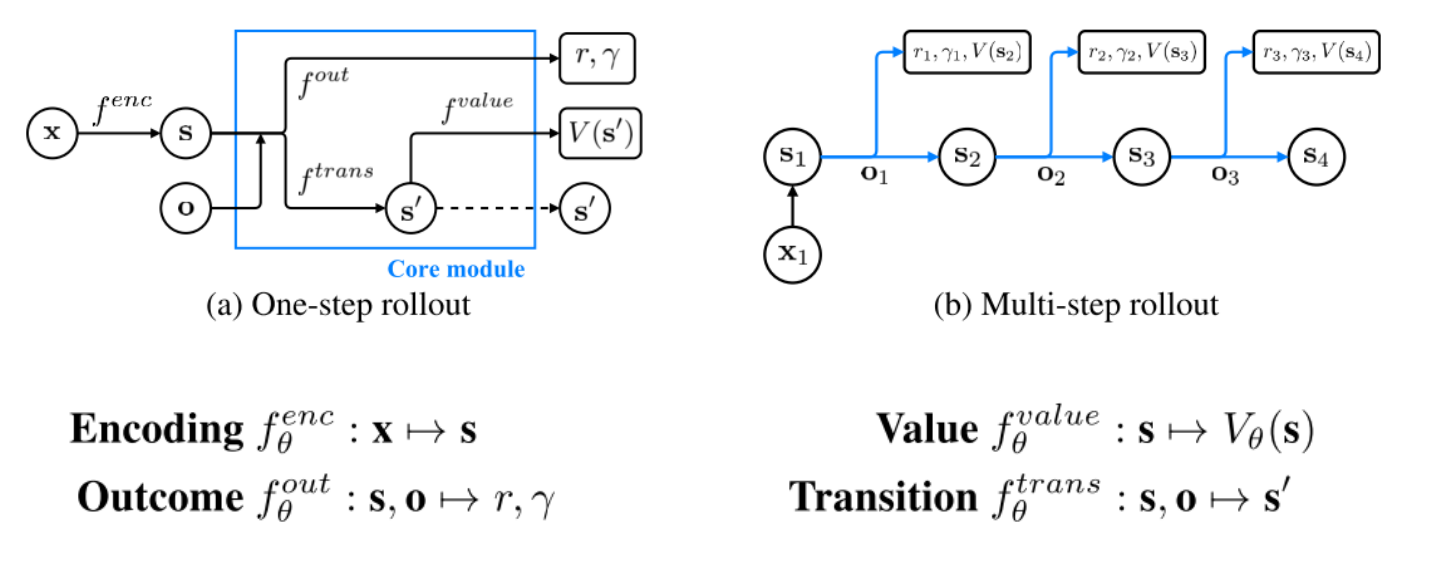

### Planning with Value Prediction Network (VPN)

|

||||

|

||||

Idea: generating trajectories by following $\epsilon$-greedy policy based on the planning method

|

||||

|

||||

Q-value calculated from $d$-step planning is defined as:

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

Q_\theta^d(s,o)=r+\gamma V_\theta^{d}(s')

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

V_\theta^{d}(s)=\begin{cases}

|

||||

V_\theta(s) & \text{if } d=1\\

|

||||

\frac{1}{d}V_\theta(s)+\frac{d-1}{d}\max_{o} Q_\theta^{d-1}(s,o)& \text{if } d>1

|

||||

\end{cases}

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

Given an n-step trajectory $x_1, o_1, r_1, \gamma_1, x_2, o_2, r_2, \gamma_2, ..., x_{n+1}$ generated by the $\epsilon$-greedy policy, k-step predictions are defined as follows:

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

s_t^k=\begin{cases}

|

||||

f^{enc}_\theta(x_t) & \text{if } k=0\\

|

||||

f^{trans}_\theta(s_{t-1}^{k-1},o_{t-1}) & \text{if } k>0

|

||||

\end{cases}

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

v_t^k=f^{value}_\theta(s_t^k)

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

r_t^k,\gamma_t^k=f^{out}_\theta(s_t^{k-1},o_t)

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

\mathcal{L}_t=\sum_{l=1}^k(R_t-v_t^l)^2+(r_t-r_t^l)^2+(\gamma_t-\gamma_t^l)^2\text{ where } R_t=\begin{cases}

|

||||

r_t+\gamma_t R_{t+1} & \text{if } t\leq n\\

|

||||

\max_{o} Q_{\theta-}^d(s_{n+1},o)& \text{if } t=n+1

|

||||

\end{cases}

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

### MuZero

|

||||

|

||||

beats AlphaZero

|

||||

143

content/CSE510/CSE510_L20.md

Normal file

143

content/CSE510/CSE510_L20.md

Normal file

@@ -0,0 +1,143 @@

|

||||

# CSE510 Deep Reinforcement Learning (Lecture 20)

|

||||

|

||||

## Exploration in RL

|

||||

|

||||

### Motivations

|

||||

|

||||

#### Exploration vs. Exploitation Dilemma

|

||||

|

||||

Online decision-making involves a fundamental choice:

|

||||

|

||||

- Exploration: trying out new things (new behaviors), with the hope of discovering higher rewards

|

||||

- Exploitation: doing what you know will yield the highest reward

|

||||

|

||||

The best long-term strategy may involve short-term sacrifices

|

||||

|

||||

Gather enough knowledge early to make the best long-term decisions

|

||||

|

||||

<details>

|

||||

<summary>Example</summary>

|

||||

Restaurant Selection

|

||||

|

||||

- Exploitation: Go to your favorite restaurant

|

||||

- Exploration: Try a new restaurant

|

||||

|

||||

Oil Drilling

|

||||

|

||||

- Exploitation: Drill at the best known location

|

||||

- Exploration: Drill at a new location

|

||||

|

||||

Game Playing

|

||||

|

||||

- Exploitation: Play the move you believe is best

|

||||

- Exploration: Play an experimental move

|

||||

|

||||

</details>

|

||||

|

||||

#### Breakout vs. Montezuma's Revenge

|

||||

|

||||

| Property | Breakout | Montezuma's Revenge |

|

||||

|----------|----------|--------------------|

|

||||

| **Reward frequency** | Dense (every brick hit gives points) | Extremely sparse (only after collecting key or treasure) |

|

||||

| **State space** | Simple (ball, paddle, bricks) | Complex (many rooms, objects, ladders, timing) |

|

||||

| **Action relevance** | Almost any action affects reward soon | Most actions have no immediate feedback |

|

||||

| **Exploration depth** | Shallow (few steps to reward) | Deep (dozens/hundreds of steps before reward) |

|

||||

| **Determinism** | Mostly deterministic dynamics | Deterministic but requires long sequences of precise actions |

|

||||

| **Credit assignment** | Easy — short time gap | Very hard — long delay from cause to effect |

|

||||

|

||||

#### Motivation

|

||||

|

||||

- Motivation: "Forces" that energize an organism to act and that direct its activity

|

||||

- Extrinsic Motivation: being motivated to do something because of some external reward ($, a prize, food, water, etc.)

|

||||

- Intrinsic Motivation: being motivated to do something because it is inherently enjoyable (curiosity, exploration, novelty, surprise, incongruity, complexity…)

|

||||

|

||||

### Intuitive Exploration Strategy

|

||||

|

||||

- Intrinsic motivation drives the exploration for unknowns

|

||||

- Intuitively, we explore efficiently once we know what we do not know, and target our exploration efforts to the unknown part of the space.

|

||||

- All non-naive exploration methods consider some form of uncertainty estimation, regarding state (or state-action) I have visited, transition dynamics, or Q-functions.

|

||||

|

||||

- Optimal methods in smaller settings don't work, but can inspire for larger settings

|

||||

- May use some hacks

|

||||

|

||||

### Classes of Exploration Methods in Deep RL

|

||||

|

||||

- Optimistic exploration

|

||||

- Uncertainty about states

|

||||

- Visiting novel states (state visitation counting)

|

||||

- Information state search

|

||||

- Uncertainty about state transitions or dynamics

|

||||

- Dynamics prediction error or Information gain for dynamics learning

|

||||

- Posterior sampling

|

||||

- Uncertainty about Q-value functions or policies

|

||||

- Selecting actions according to the probability they are best

|

||||

|

||||

### Optimistic Exploration

|

||||

|

||||

#### Count-Based Exploration in Small MDPs

|

||||

|

||||

Book-keep state visitation counts $N(s)$

|

||||

Add exploration reward bonuses that encourage policies that visit states with fewer counts.

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

R(s,a,s') = r(s,a,s') + \mathcal{B}(N(s))

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

where $\mathcal{B}(N(s))$ is the intrinsic exploration reward bonus.

|

||||

|

||||

- UCB: $\mathcal{B}(N(s)) = \sqrt{\frac{2\ln n}{N(s)}}$ (more aggressive exploration)

|

||||

- MBIE-EB (Strehl & Littman): $\mathcal{B}(N(s)) = \sqrt{\frac{1}{N(s)}}$

|

||||

- BEB (Kolter & Ng): $\mathcal{B}(N(s)) = \frac{1}{N(s)}$

|

||||

|

||||

- We want to come up with something that rewards states that we have not visited often.

|

||||

- But in large MDPs, we rarely visit a state twice!

|

||||

- We need to capture a notion of state similarity, and reward states that are most dissimilar to what we have seen so far

|

||||

- as opposed to different (as they will always be different).

|

||||

|

||||

#### Fitting Generative Models

|

||||

|

||||

Idea: fit a density model $p_\theta(s)$ (or $p_\theta(s,a)$)

|

||||

|

||||

$p_\theta(s)$ might be high even for a new $s$.

|

||||

|

||||

If $s$ is similar to perviously seen states, can we use $p_\theta(s)$ to get a "pseudo-count" for $s$?

|

||||

|

||||

If we have small MDPs, the true probability is

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

P(s)=\frac{N(s)}{n}

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

where $N(s)$ is the number of times $s$ has been visited and $n$ is the total states visited.

|

||||

|

||||

after we visit $s$, then

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

P'(s)=\frac{N(s)+1}{n+1}

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

1. fit model $p_\theta(s)$ to all states $\mathcal{D}$ so far.

|

||||

2. take a step $i$ and observe $s_i$.

|

||||

3. fit new model $p_\theta'(s)$ to all states $\mathcal{D} \cup {s_i}$.

|

||||

4. use $p_\theta(s_i)$ and $p_\theta'(s_i)$ to estimate the "pseudo-count" for $\hat{N}(s_i)$.

|

||||

5. set $r_i^+=r_i+\mathcal{B}(\hat{N}(s_i))$

|

||||

6. go to 1

|

||||

|

||||

How to get $\hat{N}(s_i)$? use the equations

|

||||

|

||||

$$

|

||||

p_\theta(s_i)=\frac{\hat{N}(s_i)}{\hat{n}}\quad p_\theta'(s_i)=\frac{\hat{N}(s_i)+1}{\hat{n}+1}

|

||||

$$

|

||||

|

||||

[link to the paper](https://arxiv.org/pdf/1606.01868)

|

||||

|

||||

#### Density models

|

||||

|

||||

[link to the paper](https://arxiv.org/pdf/1703.01310)

|

||||

|

||||

#### State Counting with DeepHashing

|

||||

|

||||

- We still count states (images) but not in pixel space, but in latent compressed space.

|

||||

- Compress $s$ into a latent code, then count occurrences of the code.

|

||||

- How do we get the image encoding? e.g., using autoencoders.

|

||||

- There is no guarantee such reconstruction loss will capture the important things that make two states to be similar

|

||||

242

content/CSE510/CSE510_L21.md

Normal file

242

content/CSE510/CSE510_L21.md

Normal file

@@ -0,0 +1,242 @@

|

||||

# CSE510 Deep Reinforcement Learning (Lecture 21)

|

||||

|

||||

> Due to lack of my attention, this lecture note is generated by ChatGPT to create continuations of the previous lecture note.

|

||||

|

||||

## Exploration in RL: Information-Based Exploration (Intrinsic Curiosity)

|

||||

|

||||

### Computational Curiosity

|

||||

|

||||

- "The direct goal of curiosity and boredom is to improve the world model."

|

||||

- Curiosity encourages agents to seek experiences that better predict or explain the environment.

|

||||

- A "curiosity unit" gives reward based on the mismatch between current model predictions and actual outcomes.

|

||||

- Intrinsic reward is high when the agent's prediction fails, that is, when it encounters surprising outcomes.

|

||||

- This yields positive intrinsic reinforcement when the internal predictive model errs, causing the agent to repeat actions that lead to prediction errors.

|

||||

- The agent is effectively motivated to create situations where its model fails.

|

||||

|

||||

### Model Prediction Error as Intrinsic Reward

|

||||

|

||||

We augment the reward with an intrinsic bonus based on model prediction error:

|

||||

|

||||

$R(s, a, s') = r(s, a, s') + B(|T(s, a; \theta) - s'|)$

|

||||

|

||||

Parameter explanations:

|

||||

|

||||

- $s$: current state of the agent.

|

||||

- $a$: action taken by the agent in state $s$.

|

||||

- $s'$: next state resulting from executing action $a$ in state $s$.

|

||||

- $r(s, a, s')$: extrinsic environment reward for transition $(s, a, s')$.

|

||||

- $T(s, a; \theta)$: learned dynamics model with parameters $\theta$ that predicts the next state.

|

||||

- $\theta$: parameter vector of the predictive dynamics model $T$.

|

||||

- $|T(s, a; \theta) - s'|$: prediction error magnitude between predicted next state and actual next state.

|

||||

- $B(\cdot)$: function converting prediction error magnitude into an intrinsic reward bonus.

|

||||

- $R(s, a, s')$: total reward, sum of extrinsic reward and intrinsic curiosity bonus.

|

||||

|

||||

Key ideas:

|

||||

|

||||

- The agent receives an intrinsic reward $B(|T(s, a; \theta) - s'|)$ when the actual outcome differs from what its world model predicts.

|

||||

- Initially many transitions are surprising, encouraging broad exploration.

|

||||

- As the model improves, familiar transitions yield smaller error and smaller intrinsic reward.

|

||||

- Exploration becomes focused on less-known parts of the state space.

|

||||

- Intrinsic motivation is non-stationary: as the agent learns, previously novel states lose their intrinsic reward.

|

||||

|

||||

#### Avoiding Trivial Curiosity Traps

|

||||

|

||||

[link to paper](https://ar5iv.labs.arxiv.org/html/1705.05363#:~:text=reward%20signal%20based%20on%20how,this%20feature%20space%20using%20self)

|

||||

|

||||

Naively defining $B(s, a, s')$ directly in raw observation space can lead to trivial curiosity traps.

|

||||

|

||||

Examples:

|

||||

|

||||

- The agent may purposely cause chaotic or noisy observations (like flickering pixels) that are impossible to predict.

|

||||

- The model cannot reduce prediction error on pure noise, so the agent is rewarded for meaningless randomness.

|

||||

- This yields high intrinsic reward without meaningful learning or progress toward task goals.

|

||||

|

||||

To prevent this, we restrict prediction to a more informative feature space:

|

||||

|

||||

$B(s, a, s') = |T(E(s; \phi), a; \theta) - E(s'; \phi)|$

|

||||

|

||||

Parameter explanations:

|

||||

|

||||

- $E(s; \phi)$: learned encoder mapping raw state $s$ into a feature vector.

|

||||

- $\phi$: parameter vector of the encoder $E$.

|

||||

- $T(E(s; \phi), a; \theta)$: forward model predicting next feature representation from encoded state and action.

|

||||

- $E(s'; \phi)$: encoded feature representation of the next state $s'$.

|

||||

- $B(s, a, s')$: intrinsic reward based on prediction error in feature space.

|

||||

|

||||

Key ideas:

|

||||

|

||||

- The encoder $E(s; \phi)$ is trained so that features capture aspects of the state that are controllable by the agent.

|

||||

- One approach is to train $E$ via an inverse dynamics model that predicts $a$ from $(s, s')$.

|

||||

- This encourages $E$ to keep only information necessary to infer actions, discarding irrelevant noise.

|

||||

- Measuring prediction error in feature space ignores unpredictable environmental noise.

|

||||

- Intrinsic reward focuses on errors due to lack of knowledge about controllable dynamics.

|

||||

- The agent's curiosity is directed toward aspects of the environment it can influence and learn.

|

||||